[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]ome images provoke indignation, others anger.

Some images provoke awe, some provoke empathy, or pity; some others that should deeply touch us instead leave us indifferent. Some images shock us, some appeal to our morality. Some images are about their subjects, some are about those who shoot them. But no image is just an image on its own.

South African photojournalist Alexia Webster started believing that her ‘street studio’ project could make a difference when a woman, 55 to 60 years old, went along to the outdoor studio in Woodstock, a suburb of Cape Town. Her street studios are usually set up with props like a chair, a coffee table and a vase of flowers. They are open to anyone who wishes to have their portrait taken and printed for free on site. “She came and she had this blanket wrapped around her. She looked so… regal,” says Webster. “She waited in line for the picture, and when she got it she started crying. She was going to send it to her mother who hadn’t seen her in 30 years, since she had left her hometown to seek fortune in the city. She had never had the money to go back.”

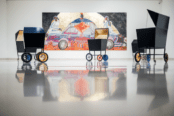

Street Studio Woodstock © Alexia Webster

Street Studio Woodstock © Alexia Webster

Webster is the winner of the world’s first conflict art award, launched last week by Artraker – a not-for-profit organisation that works on the premise that artists as witnesses of war can provide alternative narratives that encourage understanding, empathy and awareness of conflict. 17 artists were shortlisted from around 300 submissions and presented during a ceremony on International Peace Day (21 September).

[quote]Some images wield

moral authority and

with it, political

responsibility[/quote]

The name draws inspiration from the term “muckraker”, coined by Teddy Roosevelt to refer to the movement of reform-minded journalists that emerged in the early 20th century. Webster is planning to use the £2,500 prize money to take the project to Congolese and Sudanese refugee camps, and to the Turkish-Syrian border. It is in these ‘places of permanent impermanence’ that she believes her project would acquire most meaning. “When I’m there I don’t just want to take a photograph, I am going to document the process and people’s stories,” she says. “But not simply for others to understand. Telling a story is self-affirming.”

Artraker presented a variety of projects, from performance art in the streets of Colombia, to an outreach project to promote art education in schools from low-income areas in Zimbabwe, and a fictitious estate agency to denounce the expropriation of Palestinian homes in West Jerusalem. Some of the projects draw attention to little-known aspects of a conflict. Such is the case for the participatory art project Paper Txt Msgs, by Alana Hunt in Indian occupied Kashmir. Back in 2009, following a government ban on pre-paid mobile phone services in the region, more than 1,000 ‘paper text messages’ were distributed across Kashmir, encouraging people to write a text to anyone, real or imagined.

Together, they put the issue of the monitoring and blocking of phone services in the media spotlight in Pakistan, India and Kashmir, highlighting the disruption of everyday life that is part and parcel of the occupation.

For Manali-Jagtap-Nyheim, co-founder of Artraker, art can play a major role in peacebuilding processes by working with communities. “For me it’s important to have projects that are scalable and replicable, because that’s how peace organisations can work with the artists and have a bigger impact.” Artraker is supported by conflict and security consultancy Incas, peacebuilding organisation International Alert, and Integrity, a consultancy that specialises in research in conflict and post-conflict environments.

Artist Emeric Lhuisset’s work focuses on how distorted our perception of conflict is, seen through the lens of both traditional and new media. In Theatre of War he stages photographs with Kurdish-Iranian guerrillas – real setting and subjects for images that are carefully constructed in their artificiality to spark debate on the ‘taboo’ subject of staged photographs in war photojournalism. In another of his works, he follows a day in the life of a Free Syrian Army fighter in Idlib province: camera strapped to his chest, we follow him for 24 hours as he wakes up, makes food, rides a motorcycle. “It shows that so much of war is waiting,” says Lhuisset, “but we only see the action, the media events.”

The gulf war did not take place, wrote Jean Baudrillard. Not because during Operation Desert Storm in 1991 atrocities did not happen, but because the media’s representation of the war had taken precedence over the reality of war itself – for the first time, a war was reported live, in real time, a spectacle of technology and precision-guided bombs, no people, no bodies. A lot has changed since then in the way we receive and perceive information about conflict – not least because of the advent of social media.

What hasn’t changed is that the mediated experience of war often counts for more than what is actually taking place. The horrific images of the gas attack in Syria last month sparked moral outrage and legitimised calls for intervention. As if two years of atrocities and the 100,000 people who died during those months didn’t count. Some images wield moral authority and with it, political responsibility. In conflict, art and creativity can counter some of the media’s shortcomings in communicating the horrors of war and oppression, and remind us of the need to turn our attention, instead, to peace.