[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]’1[/dropcap]960s to the present’, ‘object’s relationship to its environment’ and ‘the performative process of production’ are phrases which immediately throw up the adages of the austerity of minimalism – with its compact, unitary forms and industrial materials.

A movement without presentness or sensuality.

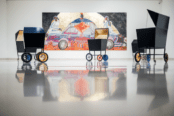

It seemed incongruous therefore to instead feel a strong urge to crawl inside Charlotte Posenenske’s imitation industrial ventilation shafts, encountered upon entering Matter and Memory at Alison Jacques Gallery. I resisted the urge yet these, now playful, structures became something of an allegorical frame of reference to the accompanying installations.

Charlotte Posenenske

Charlotte Posenenske

Vierkantrohre Serie D (Square Tubes Series D), 1967-2014

16 elements, hot-dip galvanised sheet steel

Overall: 488 x 583 x 50 cm / 192 1/8 x 229 1/2 x 19 3/4 ins

It might be relevant that all of the contributing artists are female or simply that there are formal lines of comparison to be drawn to the work of Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois in the unexpectedly tactile, and even visceral, installations. Looking back at the press release the word ‘subjectivity’ begins to overshadow the minimalist overtones since, each piece appears to bear the marks of its making and, of its maker.

Rather than being pushed out we are invited into their caress.

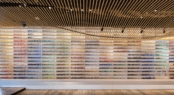

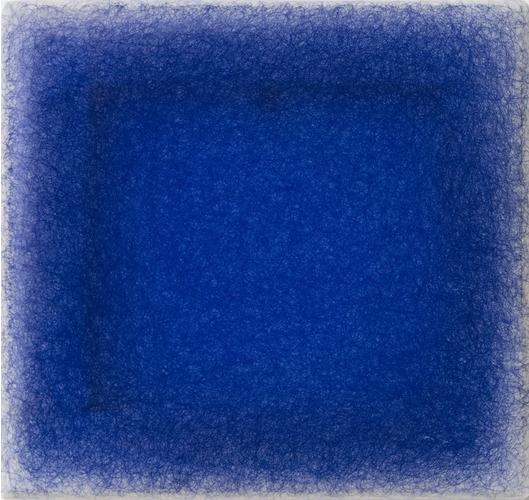

For the language at play between, as well as within, the pieces is one as much of universality as idiosyncrasy. Emblematic of this conceit is the ostensibly unassuming ballpoint scrawls of Irma Blank, which coalesce into a comparatively postage stamp-sized Rothko-esque mass in a dense Yves Klein blue.

Irma Blank

Irma Blank

Avant-testo, 15-10-01, 2001

Ballpoint pen on polyester on wooden stretcher

18 x 19 cm / 7 x 7 1/2 ins

The ease with which these references spring to mind is itself testimony to the fact that there is a bloodline running through the ink. However, whereas these forbears were notable for an all over ‘wholeness’, Blank’s work finds its rhythm in addition – the very layers of which are what invites us to fall between unitary coherence and into an interpretative space whereby we are all writers as well as readers.

Where the tongue fails this peaceful solitude of finger movements spells out a truth beyond articulation that is deeper and more felt than conditioned social interaction. There appears to be an assurance of our own contingency and temporality: a reminder of what it is to be a maker, of what it is to be human – as we read, as we write; we live.

There is a whisper of conversation occurring between the hanging plaster and coiled bronze of Maria Bartuszova’s (seemingly) effortlessly balanced creations. Formally they reside somewhere between a point of creation, seen in the spiralled cushioning of the bronze work, and the implied destruction of the plaster by its bindings.

Maria Bartuszová

Maria Bartuszová

Untitled, 1985

Plaster

35 x 25 x 25 cm / 13 3/4 x 9 7/8 x 9 7/8 ins

This linear counterpointing is complicated, however, by the parallels to a tightening fist in the metalwork and the fragility of the suspended plaster.

Indeed, the balance is not merely in their material tensions, but in their evocation of multiple levels of physical and emotional interaction.[quote]unassuming yet powerful

provocations to our innate

memories of what it is to

be a human within the matter

of the world[/quote]

The suggestive bulges of the plaster work inspire recollections of Hans Bellmer’s iconic photograph of Unica Zurn’s ‘Bound’ naked torso. As with Bellmer’s image there is a playoff between pleasure and pain, denial and sexual release, prison and play. However, where Bellmer’s photograph harmonises body and object into a seamless fetish here, the unconcealed casting lines on the surface of the plaster create the potential for a seam to rip – the objectivity is a construct.

Likewise, the bronze work could be the folds of an umbilical attachment or the puckers of an exposed buttock. Certainly there is nothing inanimate about these disarmingly simple arrangements.

It is this sense of subjective performity – of previous handling, present state of becoming, and future metamorphosis; an inherited and evolving memory, that pervades the most successful works in the exhibition. Cold metal, wood and plaster become cloaked by a homespun quality, yet with universal associations.

Rebecca Solnit writes in her beautiful mediations on family, empathy and the making and remaking of the self through the stories that we live and tell, The Faraway Nearby:

‘The self is also a creation, the principle of your life, the crafting of which makes everyone an artist. The unfinished work of becoming ends only when you do, if then, and the consequences live on. We make ourselves and in so doing are the gods of the small universe of self and the large world of repercussions…. This is the strange life of books that you enter alone as a writer, mapping an unknown territory that arises as you travel. If you succeed in the voyage, others enter after, one at a time, also alone but in communion with your imagination, traversing your route’.

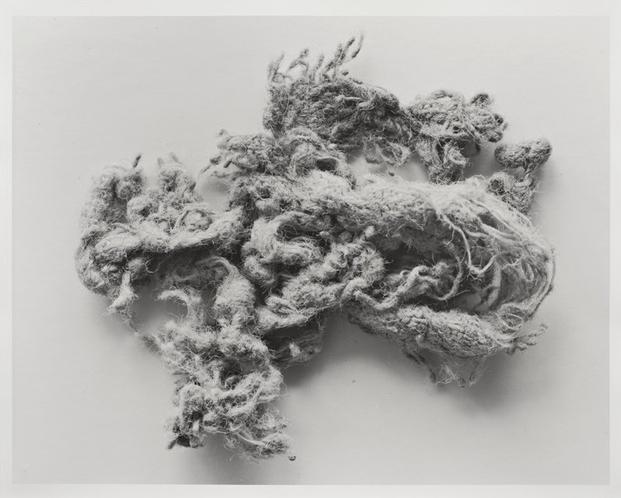

N. Dash’s silver gelatin print of cloth, which she has worked with her hands as she travels around, to the point that it can no longer sustain touch, has all the appearance of a magnified unknown landscape. The crevices and landlines, mountains and plains, however, all have the feeling of the intimacy which comes from the knowledge of another human presence – like a footprint in the sand or a wisp of wool caught on a thorn bush.

A small moment of connection has become totemically scaled for others to dive into – like a book when it is published and thereby invites its completion in the minds of readers where, its heart will receive new life.

The feeling is that someone has been here before, mapping the ground that we now retread, shaping new memories upon the foundations of another consciousness. This sense of comfort in distance is accentuated by Dash’s jute wall piece. It plays with materials and the intersections between frame and canvas, depiction and abstraction, to create a sensual, psychodynamic version of mapped space; where boundaries are as fluid as our subjective perception of them.

Despite the slightly convoluted testimony in the press release of ‘anthropomorphic metaphors that present a philosophical position in human presence’, Helen Barff’s felt-covered collections of stones could have been salvaged as much from one of Dash’s ‘landscapes’ as from the River Thames. Their ephemeral composition and form imbue them with the talismanic quality of a Joseph Beuys installation.

Helen Barff

Helen Barff

Untitled (RTS), 2004 -2014

Felt, stone

Small enough to have been carried within the personal folds of a pocket, yet displayed with the care of a museum exhibit, they blur the boundaries between a formal minimalist conceit and narrative memory.

The private becomes public and, as the tactility of the felt beckons to be re-pocketed and fondled, becomes once again a personal interpretive act. I am reminded of a recent visit to the ArtAngel installation Dig where Daniel Silver’s artistic take on an archaeological survey instilled an energy and characterisation in forgotten forms. Within that quiet graveyard of plastercasts one was imperceptibly inducted, as now, into a conversation with ostensibly deformed inanimate objects.

Amidst this quiet subversion and intricate weave of dialogues Philomene Pirecki’s wall installations perhaps feel a little strained and constructed next to the more playful and intimate works. This does not, however, dilute the hypnotic quality of these unassuming yet powerful provocations to our innate memories of what it is to be a human within the matter of the world.

Matter and Memory

Alsion Jacques Gallery

16th January-15th February

[button link=”http://www.alisonjacquesgallery.com/exhibitions/103/installation_shots/” newwindow=”yes”] Exhibition Website[/button]