[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]R[/dropcap]eeves Gabrels, currently guitarist in The Cure and formerly David Bowie’s collaborator in Tin Machine, is one of most respected contemporary musicians.

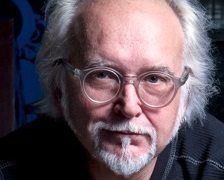

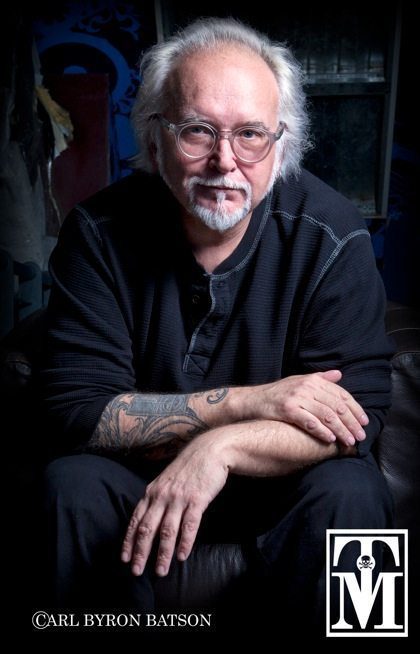

His outward appearance, a blend of art school spectacles, sharp tattoos and a neatly trimmed beard combined with an untamed grey bob and a granddad style top, sums up the man – effortlessly cool and highly intellectual but relaxed, jovial and talkative. I caught up with him during his recent tour with his other band, Reeves Gabrels and his Imaginary Fr13nds.

You grew up in New York and studied art there at a pretty exciting time, when the likes of Andy Warhol were working there. How do you think that has influenced your music?

Before I started playing, I had wanted to be a graphic artist. I was one of those kids who would get As at school. I had a method – I would come home from school, get the homework done and then I could draw. My father thought that I was too serious about my schoolwork so he talked me into taking guitar lessons because he thought playing guitar would make me more social. But they’re both relatively solitary pursuits, at least early on. Then I started playing in bands and I realised that it was more immediate but I always thought I wasn’t a natural musician. Now I look back and I realise I don’t know what makes someone a natural musician.

When I was at high school I got a scholarship and I went to Parsons School of Design in New York City. That was around 1974 so I can remember running into Warhol. We used to see him on the street corner hailing a cab. A few years after that, a friend and I went to see Bryan Ferry. It was cold outside and we were drinking Styrofoam cups of coffee and afterwards we threw them in the trash can. A limo pulls up and Andy Warhol gets out. My friend thought quicker than I did. He grabbed both of the Styrofoam cups and ran over and got Andy Warhol to sign both of them. I had it sitting on a shelf in my room in my parents’ house when I was in college. My grandmother was staying there and one day she decided to clean my room and she threw it out!

At that time I was living in the East Village, two blocks from CBGBs. 1974, 1975, Patti Smith and Television were already active and Talking Heads came along. Almost everybody seemed to have an art school background so it seemed like I had the right pedigree. I think that for me, sound has quite a strong visual reference. Especially when I’m doing music for films or instrumental stuff or if I’m just working on something that’s a song idea but I don’t have the lyrics for it, I try to make something that evokes a mood. So it could feel like an empty warehouse but the sonic equivalent of an empty warehouse.

I knew David Bowie for over a year before he knew I played guitar. I didn’t think anything was going to happen so I thought, why should I ruin this? We had the art thing in common. I met him through my ex-wife who was working for him on a tour. I would fly out to see her and bring art books. Then he started asking when I was coming out again and we would just hang out before his shows. That was the Glass Spider tour. I was there with an All Access pass and no reason for having it and he was the man at the top of the pyramid so he didn’t have to do anything. I would just sit in his room and we’d talk about art. Then she gave him a tape of my band at the end of the tour.

About four months later the phone rang and he was like, “Why didn’t you tell me?” I actually didn’t believe it was him, I thought it was a friend of mine taking the piss, so I went, “Who the fuck is this?” and he laughed and said, “Oh, you used to sit in my trailer.” One of the first times we hung out, we watched Fantasy Island with the sound off and made up the characters, the plot lines to go with it and the voices. He mentioned that and then I knew that it was him.

The first thing we recorded together was when I did a rearrangement of Look Back in Anger for a Canadian dance company that he was going to perform for. It had only been a three minute song but he wanted another two and a half minutes each end of instrumental while he was dancing. He said that he wanted it to be like the sonic equivalent of Gothic architecture and spires.

Throughout our 12 or 13 years together, it was always art reference points. Like he’d say, it needs a guitar solo but it needs to be more like a Jackson Pollack or it should be like a Superreal kind of thing or your guitar should sound like The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali. So the art school did figure pretty large and still does.

To what extent do you think Tin Machine were somewhat ahead of your time? The Pixies and Sonic Youth were around at the same time of course but the whole grunge scene in Seattle seemed to erupt around the time that you split up.

What was funny was that an album was put out called The Roots of Grunge and we were asked for a track for it. I guess if we hadn’t worn suits, it would have been more obvious but if we had been wearing torn jeans that would have untrue for us. I was unknown but for the Sales brothers and particularly for David, that would have looked like he was assuming a role. We fell on the grenade of Let’s Dance; we also reset his career. I think it set the stage for us to eventually do Earthling. It got him away from being lumped in with Phil Collins and Tina Turner which had I think, been plaguing him.

When David and I first got together to make music we realised we had both been listening to the same things – Glenn Branca, The Pixies and I knew Charles Thompson (aka Frank Black) from Boston where I had lived for 20 years, old Hendrix bootlegs, John Coltrane and Stravinsky. So we were both in the same place and it all kind of reared its head as Tin Machine.

David had at the time, framed on the wall in his house in Switzerland, a rejection letter from RCA when he turned Low in because they wanted another Young Americans. He used to say, this is probably going to end up like what happened to me with Low and Heroes, we’ll some good reviews, we’ll get a lot of bad reviews and then ten years later everyone will go, oh I really like that song. It’s like somebody said the other day, if you think you’re being humble then you’re not being humble. So if you think you’re ahead of the time, you’re already not.

Of all the projects you’ve worked on, what have you most enjoyed?

I enjoyed Tin Machine and I enjoyed the first Tin Machine record. That was like my first public outing. And with Earthling I really felt like that we succeeded in everything and it was also the first time I co-produced a David record. I was involved in production and writing all along but that was the first one where he and I really focused on it.

This seems more left field but one of my most enjoyable experiences was playing with Paul Rodgers. I was asked to do it by his manager who had heard me playing some blues stuff. Prior to that, everyone lumped me in with the New York noisemakers and things like that. I grew up playing what eventually became the classic rock sound, like Cream and Free. The most perverse thing I thought I could do at that point in my career was to go and play with Paul Rodgers and play blues with him. Jason Bonham who was playing drums called it “cock rock,” it was bonehead, 2/4 stuff, straight up. But Paul is also an amazing singer.

Right after that I went into the studio with Brian Eno and David Bowie to do the Outside record and while we were on the road, this was pre-internet, I was getting faxes from David and Eno about different concepts and what did I think. I remember sitting in my room and figuring out one night how to do a Charles Ives thing mathematically where one song was playing in 11/8 and the next song was playing in 4/4 and what note we could all come together on and what we could put on that one note to make it all seem intentional. I remember it always because I’m sitting on holiday somewhere in the Midwest and I’ve got a calculator and a music paper and I’m figuring this all out before I fax it to them and I realised that my ears were still ringing and I could still hear the crowd singing, “All Right Now”. I thought that kind of summed up my career. It’s a disparity between my enjoyment of big dumb rock and my enjoyment of the avant-garde. Maybe that’s what I do, maybe I kind of pull it all together somehow.

Those are probably the three things in my past that I would look back at with most satisfaction and now of course joining The Cure in 2012. I worked with them in the 1990s and if they had asked me to join the band then, if the circumstances had been right, I would have dropped everything and done that. When I look back, I realise that other than things of my own making, I always wanted to be in a band situation and The Cure has finally brought that into my life. It’s a fun bunch and everyone’s got their own strange quirks which makes it very interesting.

The Cure have been recording for well over 30 years. Have you learnt the entire back catalogue?

No, I had two weeks to learn 54 songs when I started playing with them in 2012. That was just going to be for the summer because they had become a four piece at that point. Then at some point they asked me if I wanted to join and I said, “Are you kidding?!” I think we’re up to 100 songs now but we do have a habit of playing festivals that force us to only play for two and a half hours. I don’t think that promoters know what to make of a band that’s trying to push for more time. Mexico City last year we did four hours and twenty minutes and we still didn’t play everything. The next newest member of the band has been there for 19 years so I’m trying to catch up and they enjoy watching me squirm. I have a thick binder where I chart everything out in case something gets called in rehearsal.

So to what extent are you allowed to put your own spin on it or are you playing it faithfully to the original versions?

Well with a band that has that many hits, The Cure makes The Cure style music and you have to think of it from the fans’ point of view. To me it seems obvious which parts of a song need to be played true to the original but you also want to breathe new life into it; you don’t want it to be a greatest hits thing even though it is a greatest hits catalogue. About half the set I’m sticking to the parts and then maybe a quarter of it I’m embellishing it and trying to keep it fresh and then the other quarter of the material, Robert trusts me to know what to do. You have to leave your ego out of it and do the right thing. But also what I enjoy is when I feel the band go “ooh” because I’ve found a new spot on the back of their neck to give them some goose bumps. When I look back, I think one of the reasons why people have asked me to play their songs is because I seem to be able to bring a little bit of the unexpected and make it a little bit dangerous, or make it surprising but still not ruin it for the fans. Although I’m sure a bunch of people who came to see Tin Machine would feel otherwise! But then that was all original material; it was all stuff we wrote together.

Are there any plans for you to write some new material with The Cure?

Things like that with The Cure, there are always plans to do stuff but that question is for Robert to answer. I know the fans always think it’s the last time but I don’t think they have to worry. It’s alive and well, it’s just not my place to talk about those things. Robert likes to; it’s his band. I don’t want to be “that guy” (laughs).

So is Imaginary Fr13nds your band or is a three-way split on decisions?

The new record is eponymous, Reeves Gabrels and his Imaginary Fr13nds and there are a couple of songs that we wrote together and there are some songs that were written in various combinations, some with other people and some songs by other people that we’ve completely reworked. We’re also playing a lot of stuff from my other albums and we play one Tin Machine song and one I wrote with Robert (Smith), Yesterday’s Gone. The hardest thing for me is singing something that someone who has an iconic voice like David Bowie or Robert Smith or Frank Black has sung. I can’t sing like any of them so I have to find my way to make it work.

I moved to Nashville in 2006 and I’ve being playing with these guys since 2007 and we’ve played with other people. I guess I’m the one who gets to take any financial risks but it feels like a band. I’m the one that has to pay for the airline tickets! It was my idea to do this because I’ve never played in the UK with my own band and I thought it would be fun to do it. Right after we (The Cure) came back in September from North America, I knew they would all want to take a few weeks off so I knew I had this window.

Instead of taking time off, I decided to book this as quickly as possible. So it was booked at short notice but we’re having fun. The three of us have spent so much time in vans driving around the US, staying three to a motel room so it’s kind of like we’re behaving like 20 year olds.

Why did you move to Nashville?

After I quit working with Bowie in late 1999, I went to LA and while I was there I didn’t feel right. It turned out I had contracted Lyme disease. I’d had it for a long time but I hadn’t known. There were things like I’d drive somewhere in the car and then not remember where I was or why I was there. It took me about a year to find a doctor who actually did blood tests and found out I had pretty bad Lyme disease. So then I had to take medication that they give you for Anthrax, but if you have Anthrax you’re only on it for six weeks and I was on it for twelve months.

One of my closest friends owns a club in Nashville and I had played there with another version of a band I had and I liked it. A mutual friend of ours was moving to LA and needed someone to rent his house so he rented the house for me while I was recovering. He said it was for paid for a month so I should come out and if I liked it, I could stay. I liked it.

I’m in East Nashville, which is an interesting community. It’s changing now and becoming more focused. I think it’s the last vestige of the old music industry paradigm where things are being done the old way. A lot of people who don’t like the change in the music industry who lived in New York or LA are moving there and it’s not the Nashville it was eight years ago. But then before I got there people were probably saying the same thing I’m saying now, I’m sure. I would have shut the door after I got in! But it’s still more of a country town; country music hangs over the town in the same way that the film industry hangs over Hollywood. You can’t get away from it and a lot of it is pretty vile.

One quick question to finish off; if you could play with any band, living or dead, who would it be?

You know, I’ve always liked Julian Cope but he’s always had a great cast of characters and I wouldn’t want to ruin that. But I would love to do maybe a one-off thing with him. But I don’t know anybody that he knows so I have absolutely no idea how that could ever happen.

It’s out there now.

But the final part of that is that I’ve never been happier than to be where I am.

So Robert Smith has nothing to worry about?

Oh, I don’t think Robert’s worried about anything!

All words copyright Sarah Corbett-Batson 2014

The Cure play Hammersmith Eventim Apollo on 21, 22 and 23 December 2014.

All photos copyright Carl Byron Batson and not to be reproduced without express prior written permission

Really interesting interview. I would love to hear a collaboration between Julian Cope and Reeves Gabrels…