Barrett's mythologised life finally comes down to earth in the first major exhibition of his art and letters. But is he a little too human?

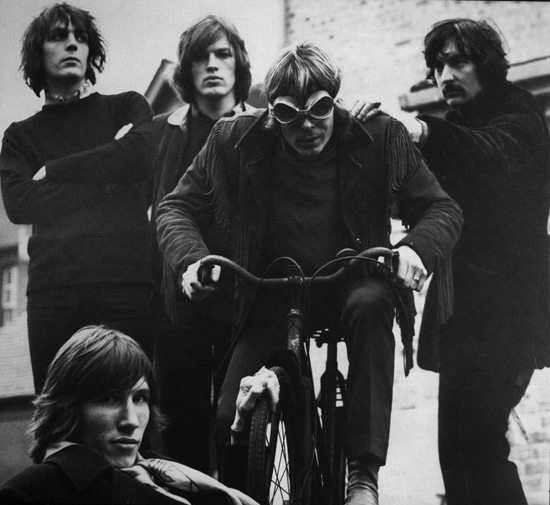

January 1968. Crammed into the back of a van, Pink Floyd, minus Syd Barrett, are on the road to play another gig. Syd's been pretty erratic of late. Although the founder of their band and a great musical innovator, he's been too depressed, too high or simply too unstable to perform.

In one rehearsal, Syd brings in a new song entitled, “Have You Got It Yet?” As the band struggle to work out the arrangement, Syd keeps asking, “Have you got it yet?” until they realise he's been constantly changing the arrangement. It's all a joke. They're never going to get it. They're never going to get Syd either.

So back in the van, with Dave Gilmour as stand-in for the increasingly unreliable Syd, someone asks, “Shall we pick Syd up?” The reply comes: ”Let's not bother” and Syd Barrett's contribution to one of the most influential psychedelic rock bands in music history is over.

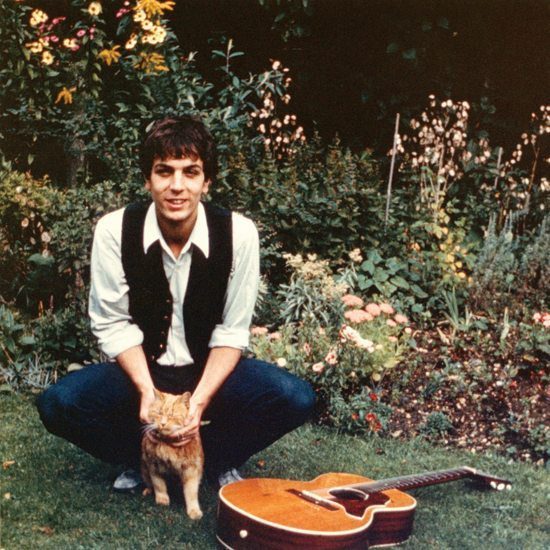

Although he's out of Floyd, this isn't the end of Syd's life as an artist, as the Generation Idea exhibition of his Art and Letters illustrates. For Syd, born Roger Keith Barrett amidst the spires of 1946 Cambridge, music, painting, poetry, letters, even gardening, were ways in which he could express his soul. While much of the musical world spent the next four decades mourning his departure from Floyd and dreamt of the amazing contributions he could have made to music; Syd quietly painted and tended his garden, until his death in 2006 at the age of 60.

So given the mystique around Syd Barrett's supposed genius, seeing his art and letters is a rare opportunity to see his creative output outside of Floyd. For what is revealed is a deeply loving, deeply playful, yet deeply insecure man. This might come as a surprise for those who prefer the myth of the eccentric, creative genius. But all myths need debunking.

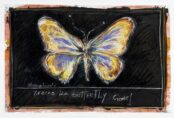

Barrett studied at the Camberwell School of Art, and much of the artwork on display dates from this period in his life. I was initially surprised by the child-like nature of many of his paintings. Some of the watercolours look like they had been painted using primary school materials, complete with coloured borders ready for Teacher's wall display.

Sprinkled amongst the watercolours are far more accomplished works, the best being “Untitled 6”, a great tortoise, and “Untitled 8”, a scene from the coliseum, where distressed children hide from lions in what appears to be a walk through antiquity gone wrong.

Intrigued, but somewhat under-awed at this point, I turned to face a wall of letters, letters illustrated with doodles, stick figures and caricatures. Letters to his lovers; Libby Gaudsen and Jenny Spires. For a moment I wondered if I ought to read Syd's outpourings of love. These were never meant to be published or shown to the outside world. I felt like someone staring at a car crash. Yet what I saw was engrossing. I began to see something very human and wanted to know more.

One of the first letters reveals a man who is in no way sure of any great success. In recalling a recent interview Syd writes, “…I only hope they accept me, otherwise I believe plumbing is a very steady job.” Such humble words from someone so lauded. Later he tells his lover he doesn't think he'll be famous. He just wants her beside him in his warm bed.

His letters speak of someone simply doing what comes naturally to him. The childishness of his handwriting, the doodles and scrawls all echo the dreamy voice that reverberates through his Pink Floyd recordings. Writing to Libby, he tells her that when recording he can't hear his own singing and he is sure that it would've been a “whopping drag” for her if she had come along. To illustrate his point, he adds a picture of himself wearing a huge set of ear phones.

What consumes more and more of the letters are not concerns for his musical career, ideas for songs, paintings or any other creative works, but his deep desire to have his lover with him all the time. “All I can do is sit and spell – Daring.” He thanks her for giving him another chance, and tells her, “Please write Lib, I'm always thinking of you.”

More and more his letters reveal his deep, all consuming love. “This morning I engraved your name on my leg…” It begins to make sense how someone this sensitive could crack in the face of fame, retreat from the world and sink into obscurity.

The exhibition is filled with many rare photos from the band's early tours, as well as many prints to buy. But it is the letters, the outpourings of love that makes Syd, or Rog as he signs himself, less remote. No longer is he an eccentric whose mind is unfathomable, but someone who could easily have become a plumber, a regular fellow dreaming only of his lover. For some, this may be all too human, but it is the very humanness, the very insecurity and sensitivity of his nature that makes this exhibition well worth a visit.

Syd Barrett may never have wanted fame. He may never have wanted his letters hung on a wall either, but what they offer is a deeply human link to one of the 20th century's biggest cultural icons.

Barrett, The Definitive Visual Companion, published 18th March by Essential Works, www.barrettbook.com

Syd Barrett | Art and Letters, 18th March – 10th April, Idea Generation Gallery, www.ideageneration.co.uk

Photo Credits:

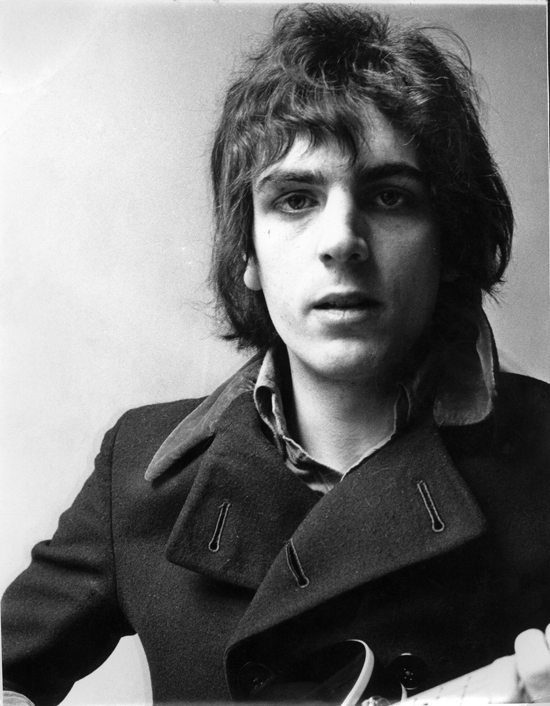

111 – Courtesy of Pink Floyd Music Ltd Archive

13a – Courtesy of the Estate of Roger Keith Barrett aka Syd Barrett

110 – Courtesy of Pink Floyd Music Ltd Archive

187 – Roger Barrett / Courtesy of Libby Gausden-Chisman

“There are too many Andrew Southerns in the world. I’ve checked. There’s a whole bunch of us. It’s kind of annoying. In an over-populated world it’s humbling to realise there are multiple versions of you. Maitland, on the other hand, is a name you don’t see.

Like any writer, I need to make my mark. So I can sink into the Andrew Southern soup or go the Maitland way. It’s a name my ego loves and humility shies away from. I can’t sink into the soup. It’s not my style. So grandiosity it is. You can call me Andrew, though. Not Andy. There are too many of those too.