[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he story of the abduction of Persephone and the subsequent search for her daughter by Demeter has been the subject of many texts and translations throughout history.

Each version adds a new dimension to the tale–another layer to the textual blood line.

Common to the iterations, however, are the themes of loss, isolation and displacement; the humanising characteristics of the mother-filial bond; and the tensions between life and death, world and underworld, interior and exterior.

It are these themes which are explored in Generation: a collaborative work by Czech filmmaker Tereza Stehlíková and American sculptor Rosalyn Driscoll, both members of Sensory Sites, an arts collective specialising in multisensory practice.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Cave of the Eye (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Cave of the Eye (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

For this exhibition the artists drew on the Persephone-Demeter myth as a guiding principle; from which to explore the progression of life through three generations of women.

Stehlíková filmed her grandmother, mother and daughter in their country house in Bohemia and Driscoll produced sculptures made of translucent, amber colored rawhide (dried cow skin), which receive and transform the video projections. Through their combined practice the artists create a vision of what the poet David Baker describes thus:

If we live in the mind, then the mind lives in the body, and the body lives in a particular time and place in the world, taking sustenance, loving, working, labouring in that time and place.

Baker speaks of a lived memory whereby the past is mourned yet, learned from, in order to direct the present towards the future.

The myths and traditions that are passed down from generation to generation – reinvented and retold – are those which are never fully resolved.

There are tensions within memory and human relationships which remain secret, binding us inexplicably together as much as they pull us apart.

Upon our entry into the world we mythicise our existence through our individual responses to our environment. As we become aware of our identification and difference from others this becomes part of a collective social myth with which we attempt to make sense of our environment.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, In the Field (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, In the Field (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

We never lose, however, a fascination for those stories that are sometimes incomprehensible in their surface details, yet go to the heart of our existence. These are the stories that resonate with the common sensory experience of the moment of our birth – a violent displacement leading to an awakening into a freshly viewed world; not quite knowing what will come next.

It is this notion which makes sense of what appears at first to be a paradox in the artists’ collaboration– an exhibition based around touch and the senses whereby correspondence was actually enacted over Skype and emails.

However, as we are pulled inextricably through the gallery spaces, it becomes clear that this method in fact simulates the uncertainty of birth and motherhood. Both processes are informed by an intuitive response to a world and experience beyond our control which we can attempt to rationalise, yet never fully grasp except as a physical sensation.

Read and lived myths are therefore a point of both association and departure in the making of the work – what in fact unites them so seamlessly is the realisation that communion is present more in what is felt rather than said.

Their shared experience of motherhood became a point of correlation, re-enacting the bonds that they were exploring in the myth through a shared creative vision that connected their own geographical and generational gap.

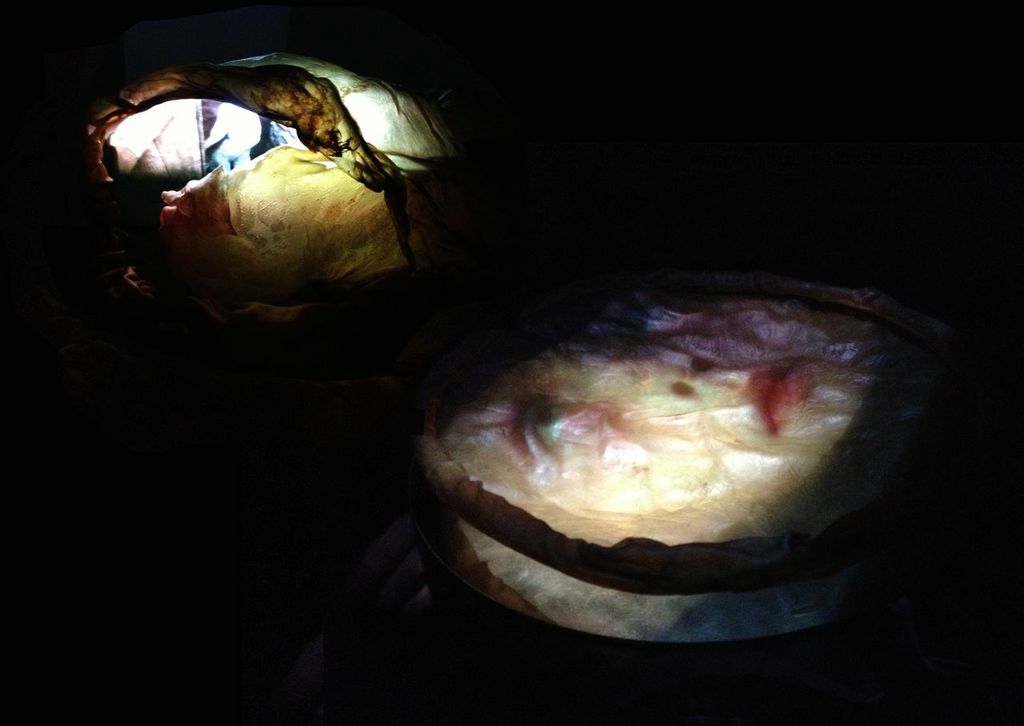

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 1) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 1) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Uncertainty is perhaps an understatement for what Persephone must have felt – ripped from the flower fields of her inexperience and submerged into the depths of Hades.

However, it is this submersion into the shadows of the world – what Jung would refer to as the subconscious – which in fact, upon her return to the terrestrial world, announces Spring. Displacement into our own interiors where connection with the world is exclusively through our bodily memory of it, brings about a fresh interpretation.

A quaint domestic scene of an old lady sat in a beautiful garden is lightly projected onto delicately suspended white paper. A dog runs into the shot, circles and turns away. One might almost anticipate the laughing of children in the distant fields, running to greet their waiting grandmother.

And yet, waiting is what proliferates this seemingly innocent observation. The papery layers flutter slightly – like a shroud breathing with the anticipation of the exhalation of those recently departed. The grainy wash of the film and distanced gaze oscillate in a fixed timeless present – the dog runs back again. The world is as it is and yet somehow disconnected.

Balancing on the steps to the lower floor, a glance back to the receding light above sees the present, future and past interweave. There is an unspoken question: dare we continue?

Below, swathes of greyer hues consume the intrepid; illuminated by pockets of gorgeously visceral forms, pulsating with light and flickering forms.

Myth entwines with observed experience as, the projections of Stehlíková’s family merge with allegorical materials. Forms mimicking the implements used traditionally to gather seed are referenced. The contorted shapes draw the eye in and out of the projected domestic space – the boundaries of which overflow into the creases and crevices of the sculptures.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 2) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 2) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

The embodied and implicit tactility of the pieces seems to ooze – one is almost compelled to dive in, and yet, also repelled. The push and pull mimics the body as a site of both pleasure and pain.

The intimacy and separation of motherhood, common to both artists, is then a further reaching metaphor for our constant battle with out bodies and the creative process itself – both connecting with and defying our will at different points in our lives.

[quote]Motherhood in a sense

is a performance, that

the artists too are

re-rehearsing[/quote]

The pulses of the moving figures animate the dead – death is present at the point of birth; death is in life. The projections penetrate and contort; artistic practice is a method for exploring both our own subconscious and connecting us with a shared emotional experience.

Figures appear, dissolve and reappear; just as filmic walls meld with physical hide. Indeed, where the collaboration is most successful, the interior of a Bohemian house completely assimilates a cavelike presence, heightening the sense of imprisonment and claustrophobia.

The house has become a stage through which the dichotomy of connection and separation – implicit in the women’s roles as potential, current and past mothers – is revisited, heightened and thereby explored. Stehlíková, explains:

‘I was interested in the space as much as my family, how the closeness suggests the tensions that are running between the women at different stages of their lives’

The revisiting of her childhood home itself became a ritual for Stehlíková. The annual trip lent her both the impartiality of the observant camera’s eye, attending to nuances in the relationships between the women of her family and the emotional tug of her own blood connection.

Guided by the story, new realisations of those closest to her began to open up and hence, discoveries about herself. The claustrophobia inherent in the sculptures reflects, perhaps, her re-immersion into the home environment – uncertain of role as mother, daughter, granddaughter, just as the skins teeter on the brink of interior psychology and physical embodiment.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 3) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Threshold (detail, 3) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

The spiralling forms in turn, draw the viewer into the private drama too – what was airy countryside has given way to an intensity of colouring and texture endowed by the hide. The residual honeyed scents of beeswax – used as an evocation of its talismanic function in the Eleusinian Myths – infuses the air with an intense sense of ritual and mystery. The loss of innocence and awakening of sexual experience permeates the room in every shadowy crevice.

Persephone ‘the honeyed one’ reaches for the ‘honeyed’ pomegranate.

The lure of the darkness within the secret rituals of female and human experience, lived through the body, takes us into a deeper understanding than the women – who, like the broken halves of ‘Threshold’- communicate in their day-to-day lives.

As the older woman loses her sensory perceptions of the world, no longer inquiring after new meaning and experience, Stehlíková’s daughter disappears from sight – merely round the corner in the house yet deep within the context of the viscous undulations of Driscoll’s shell-like vessel.

Cycles of life, its decay and renewal, are a constant presence. Our initial dependence and basic need for maternal connection is transformed into the complexities of love that contain the shadow of separation – from our offspring, from our intuitive experience and from the world itself.

This interplay between identification and individualism is effectively captured in the two-tiered mirrors of ‘Threshhold’ where the glass surfaces reflect the faces of the women engaged in day to day rituals – such as brushing each others’ hair – from different spatial proximities. The poignant intimacy of the rituals confers the strong impression of sensual memories between generations.

In addition, the fact that Stehlíková has deliberately adorned the women with flowers and robes for these ‘ceremonies’, emphasises the idea of re-performance down the ages – an ancient rite both given and imbuing new life. Motherhood in a sense is a performance, that the artists too are re-rehearsing. The true mirrors are immaterial.

The claustrophobia of the higher mirror image, juxtaposed with the release of the shell sculpture across the room, also recalls Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage and the realisation of our own subjectivity. Where there is connection there must also be displacement – in order that the reflections become resolved.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Winnowing (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlikova & Driscoll, Winnowing (detail) 2012 – Image courtesy of the artists and GV Art gallery, London.

Stehlíková mentions that the women in the films appear to be ‘waiting for something’, and the assertion recalls the uncanny experience upon first entering the show. Glimpsing again the pulsating form of ‘Cave of the Eye’ before ascending the stairs, the beat now speaks with a hopeful expectancy of new life. The dead live on in each pulse. This has not been a linear narrative but a cycle.

In turn, the shroud-like forms of the white paper which greet blinking eyes, now seem imbued with – less of a sense of the abject – as a contemplation of the fragile line between presence and absence that forms a continuous sequence as an active part in life.

By embracing the commonality of shared bodily and creative experience and – in turn – the passage of time, our eyes adjust to the light anew; ultimately enriched by their immersion into this mesmeric labyrinth.

Generation

A collaborative work by Rosalyn Driscoll and Tereza Stehlíková

GV Art

49 Chiltern Street

London W1U 6LY

+44 208 408 9800

Exhibition from 26 September – 5 October 2013

Daily from 11am – 6pm

For further details see the gallery website