[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]J[/dropcap]oseph Beuys and Jörg Immendorff : Art Belongs to The People!

Curator Sir Norman Rosenthal is enthusiastically beckoning to a group of timorous looking students peering around the partitions of the Art Belongs To The People! show at The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

‘Young people are wonderful’ he explains, ‘they should come and see this.’

Rosenthal sits erect and energized in the midst of a frantic to-ing and fro-ing to complete the installation of some of the larger vitrines, currently pushed back against the walls. The prospect of a group of schoolchildren descending upon this precarious arrangement fills the eyes of the gallery staff with barely suppressed terror.

And yet, the invitation seems apt for a show focussed on a previously overlooked dynamic between the grandfather of the post-war avant garde, Joseph Beuys, and his politically mobilized student at the Dusseldorf Academy: Jörg Immendorff.The Ashmolean itself is a fitting theatre for the restaging of this dialogue due to its university context and clear mission to address the proposition that great art acts as a document of human history.

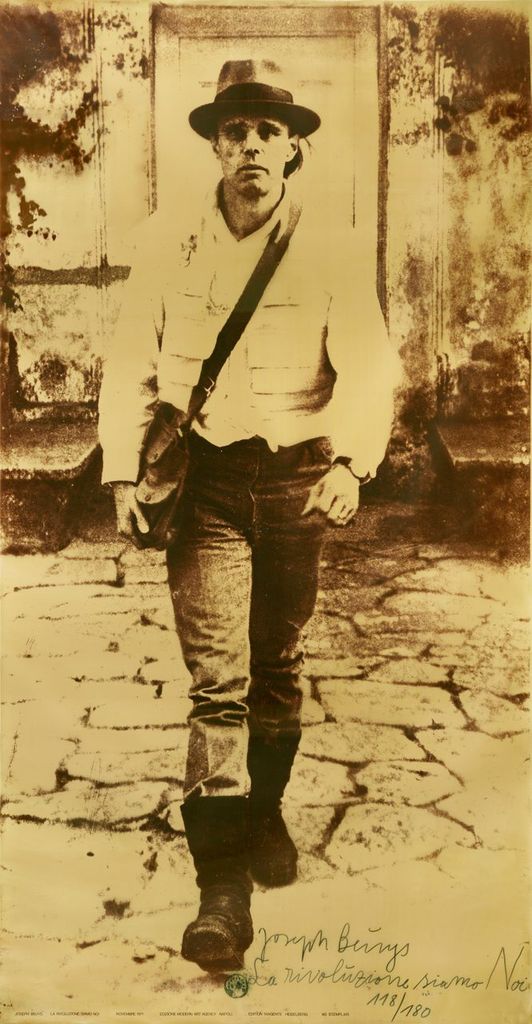

Rosenthal’s summons to the school group could almost be an echo resonating from the photograph behind him, showing Joseph Beuys striding towards the camera. For Sir Norman, as with Beuys, there is a firm belief in art’s ability to change the way that people think.

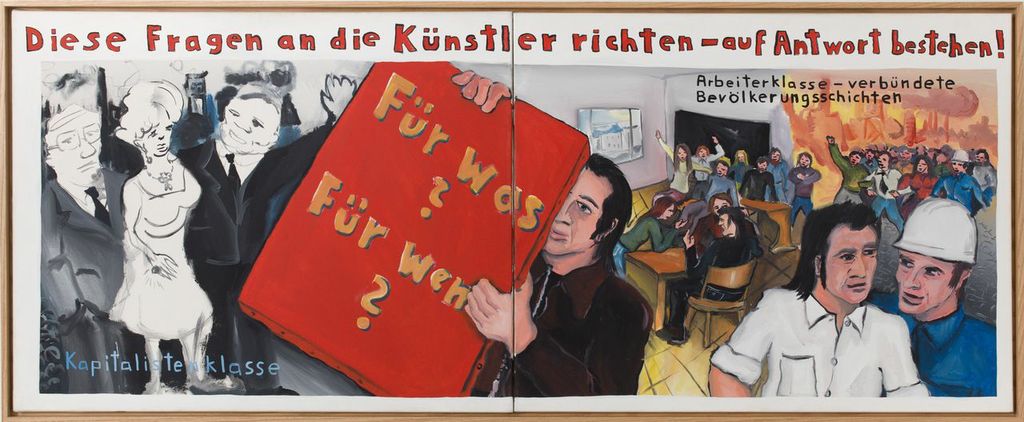

Mao’s little red book

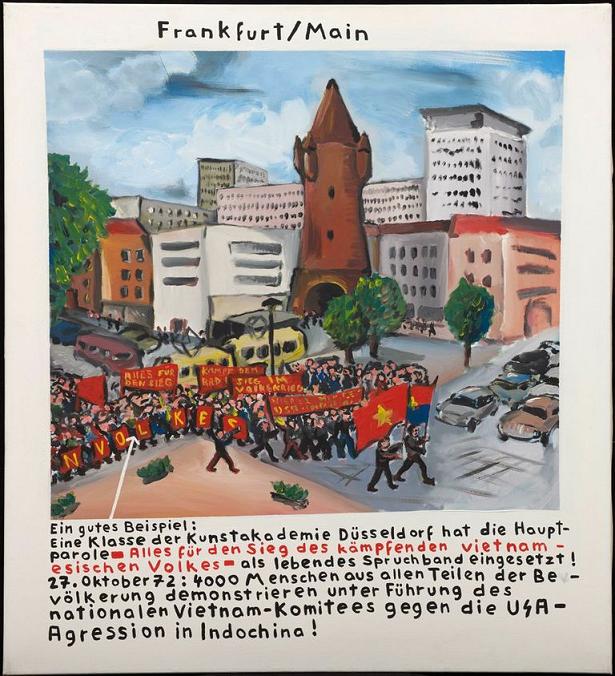

The political element inherent in this mantra is immediately evident in this display in collaboration with the Hall Foundation, through the initial dominance of the vibrant confidence of Immendorff’s early paintings. The Maoist red is immediately striking; resonating with the firmly held beliefs of the student movement between 1970-76, when the notorious little red book was a staple accessory to the young and socially engaged.

Text is integral to the works – these are paintings meant to be read like propagandist pamphlets as well as (or arguably instead of) aesthetically contemplated. This is neatly emphasised by the fact that the exhibition catalogue provides transcripts of the German phrases – these are not artistic mediations on the Romantic idea of the unknown but rather very real commentaries of the times that announce their content from the outset. Paint thereby creates a context through which narrative can be structured and rearranged for satirical purposes.

The paintings such as the monumental ‘Die Geschichte der EPAS’, though bearing the hallmarks of the more complex imagery and juxtapositions that would develop in his later work, have a naivety that verges on the brash. Within the context of the exhibition they serve more as specific documents of their time.

With the motive of the display in mind however, they fulfil a role in charting the shifting sensibilities of the artist from fiery student to a more mature and considered approach.

Art into Society : Society into Art

Indeed, it is Immendorff’s technical ability that perhaps drew Rosenthal to re-examine the painter in the context of a retrospective, having initially excluded his work from the 1974 show of Contemporary German Art at the ICA – Art Into Society: Society into Art. This was precisely for its propagandist nature which stood in contrast to Beuys, who was the central focus for the show. Here though the tables have not quite turned, but have certainly shifted in favour of the younger painter.

Before transferring to Beuys’ tutorage Immendorff had studied under the famous scene painter Teo Otto, and it is this apprenticeship – combined with a more Beuysian, material led approach – that prevails through his later work. Having rid himself somewhat of the shackles of Maoism, like his contemporary Penck, Immendorff turned his attention to the topic of the division of Germany and Europe.

This preoccupation became reflected in his grand cycle of paintings: Café Deutschland. By merging the Romantic tradition of Manet, Van Gogh, Bechmann and Kirchner to depict café life, with the abstract discourse of art after 1945, Immendorff evokes the divide but also potential unification of Germany.

Culture, politics and the seedy underworld of German clubs

The fantastical assemblages of real life characters from culture, politics and the seedy underworld of German clubs have a nostalgic element of a bygone time, redolent with the dark spirituality of Beuys’ work. Conspicuously lacking in text, apart from the handy ‘labels’ beside the protagonists, they also speak of a creative struggle to position himself against both Conceptualism (as a painter) and New Expressionism (with his nods to a destroyed Romantic tradition).

What we see is a merging of his iconoclastic political stance with an increasing identification with the notion of the role of the ‘artist as outsider’ in their own right – a position both lonely and open to aesthetic possibility. It is perhaps unsurprising that, in his later work– and most evidently in his commission to design the sets for Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress – we see Immendorff turn to Hogarth for inspiration, using the canvas and the history of art as his stage. Painting, for him, is therefore not such a far cry from Beuys’ performance based practice.

New dialogues

The end of his life therefore saw a renewed fervour as, though ailing in health with a degenerative disease, he embraced technological advances to sketch on computers and rely on the aid of assistants. If, as we have seen, great art resonates through history as both a reflection of its times and initiator of new dialogues, then this is where Immendorff earns his place.

The last paintings have a more implicit aura and complex abstraction, though still echoing with the sensibilities of his early work. One cannot help but see parallels with Richard Hamilton’s collages in the untitled works of 2005.

Lidl living

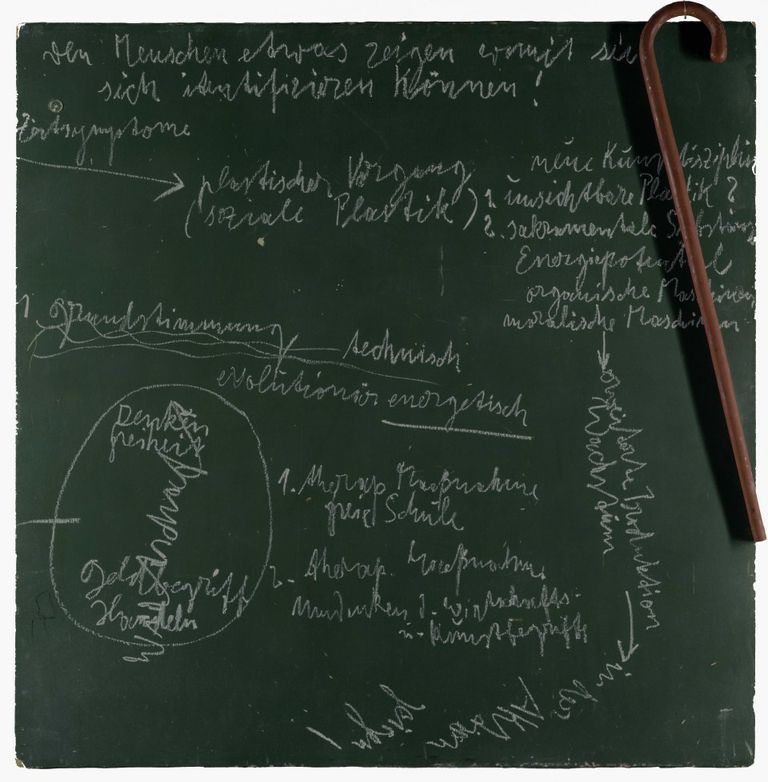

Beuys’ presence on the other hand is, from the offset, a haunting one. The eye is drawn immediately to the blackboard at the far end of the exhibition, which bears the memory of a talk that he gave in Achberg, Germany, opening with the premise: ‘Every man is an artist’.

The use of the blackboard came directly from Immendorff’s own diagrams, upon the same surface, for ‘Lidl living’ – a Utopian ideal to counter a degraded culture. The works are displayed in sequence, at first blurring the boundaries between teacher and student.

The sense in Beuys’ scrawls of a musical echo, and the presence of organic symbolism, however, gives them an aesthetic that exudes his idiosyncratic spiritualism, rather than being primarily ironically didactic. Like the other rational props of the upended walking stick, modest coat, axe, tin cans and other ephemera, the blackboards are vehicles of a mystical experience.

An art of revolution

Beuys’ use of materials from lived experience, such as the fat and wool used to treat his wounds when his plane crashed in Russia during the war, lends his work a poignancy that is initially lacking in that of his campaigning student.

His is an art of the German Romantic tradition, infused with a personal mythology – an art of revolution through its insistence on humanity, communality and natural existence in the world, against the machinery of the age – an art of the people in every sense.

Yet the documentation, photographs, texts, proposals and videotapes also feel like ghosts in another way. They lack the physical presence of the shaman who would transform the walking stick into an Eurasian staff. Where amidst these carcasses is the charisma of the personality in the photograph leaving Dusseldorf University upon a dismissal for subversive practice?

Whereas Immendorff’s paintings speak out with an unrelenting presence, Beuys’ relics attest to the fact that his work exceeds visual representation.

Rather than lamenting a disappearance however, this quality seems to lend itself as a metaphor for the act of teaching which is foregrounded in the exhibition. Beuys’ ‘Rose for Direct Democracy’ itself illustrates a transition from an unyielding system into an organic one, and the fact that it is replenished at each showing suggests that this constant renewal and regeneration is a message that stands the test of time.

Likewise we see the influence of his theories running through the development of his student. This is an art of dialogue that refuses the consumerist packaging of the Revlon perfume which advertised the American-Soviet rocket launch, depicted mockingly in Immendorff’s satire. It is also an art of irony, in the sense that even in absence, a human concern is present, resonating in and with its time; beyond its time.

At the centre of the exhibition is an Assyrian stone relief- a relic from the permanent museum collection focussing on the body in Ancient Art. The bodies are gone, making way for this ‘new’ art yet, this figure lingers. It is clutching what appears to be a handbag and, as we turn to the photograph of Beuys to the left we can perceive a similar satchel.

Life is seriously unserious and we will always, it seems, carry a handbag – such is it to be human.

Joseph Beuys and Jörg Immendorff : Art Belongs to The People!

The Ashmolean Museum Oxford

A free display open in Gallery 2 from 10 April until 31 August 2014

[button link=”http://www.ashmolean.org/exhibitions/” newwindow=”yes”] Ashmolean Museum Website[/button]