[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n another post, I compared Bulawayo, Zimbabwe to Monrovia, Liberia in that they are both cities that have suffered terribly from mismanagement and neglect in the last several decades, such that a visit to either feels like one has walked into a stage piece from 1978.

Neither city has experienced much new construction in the last thirty years, and this is evident in everything from cracked pavement to broken streetlights, from faded paint to rusted steel.

However, there is another way in which Zimbabwe and Liberia compare, and this one is far more disconcerting for the average traveler – the use of the United States dollar as the main unit of domestic exchange.

If you’ve traveled often through any region of the world, you’re probably used to operating a kind of internal forex everywhere you go. You may go to the ATM or use traveller’s cheques (do people still use traveller’s cheques? I honestly have no idea), but the end result is a proliferation of colorful new bank notes in various denominations, a plethora of new coins in different shapes and sizes, and a clean slate of personal knowledge on what costs how much where.

In West Africa, I had to remember that a dollar was equivalent to roughly 500 cfa, but that in Ghana, a dollar was roughly the same as one cedi. Okay, one hurdle jumped, but then there were the new prices and the old prices, a result of a World Bank sponsored revaluation exercise. A banana might cost 500 cedi, but that was the old price, before they cut off three zeros, so really that banana costs fifty cents. In Sierra Leone, that banana probably costs the same, only now it’s 5000 Leones.

If you’re primarily traveling to Francophone West Africa, you’ll be relatively fortunate that the cfa covers seven countries, but if you plan to leave any of the former French colonies, you’ll still need to get used to the Ghanaian cedi, the Liberian dollar, the Leonean leone, and the Guinean franc, which is the same as the West African franc but with an extra zero for good measure.

To add to the mental gymnastics, one is constantly reminded that the West African monetary union drastically devalued the franc in the early 1990s, and yet the language of commerce just took it in stride and never bothered to readjust. Thus, a 1000 cfa note is often called 200, a fifty cent piece is known as a ten, and remembering the conversions and the vocabulary while negotiating over a pack of oranges can quickly become a frustrating but occasionally hilarious cultural exchange.

It’s a bit easier in Southern Africa. The South African rand has fallen to 10ZAR : 1USD. Lesotho’s Maloti is tied to the rand. In Botswana, the pula is doing a bit better at 8BWP : 1USD, and in Zimbabwe, well….

Zimbabwe, like Liberia, uses the US dollar in most day-to-day transactions. This makes sense for Liberia: the country was established as a new colony for freed American slaves in 1822 and gained its independence twenty-five years later. Its political end economic systems have always been linked to those of the United States. It has its own currency, the Liberian dollar, which is pegged to the US dollar at 75 LRD : 1 USD. The two are easily interchangeable, and, owing to their historic ties, the use of the US dollar doesn’t seem strange at all.

Zimbabwe, on the other hand, uses a hodgepodge of US dollar, South African rand, and even Botswanan pula. Zimbabwe has no currency of its own, at least not lately.

Some who follow African politics may remember Zimbabwe’s catastrophic inflation of the last decade. This wasn’t the result of the global economic crisis, or of US/EU sanctions as some here claim, but neither of those helped matters much as inflation peaked at 231,000,000% in 2008. Zimbabwe’s massive hyperinflation is the second worst in the history of the world. Daily inflation peaked at 98%, meaning that prices doubled every 24.7 hours. Prices soared. If one had to buy diesel for a car or generator, it was best to buy in the morning, prices could increase many times over by afternoon.

[quote]bank notes with denominations

ranging from one cent ($.01) to one

hundred trillion dollars

($100,000,000,000,000.00). [/quote]

The crisis wiped out pensions, cleared bank accounts, and reduced the country to a barter system. One lodge owner told me that he allowed a friend of his to pay for his accommodation in cans of paint. In an attempt to control prices, the state ordered police into stores and businesses, froze prices for certain goods, and commanded shop owners to roll back prices to a previous date, effectively forcing business owners to halve their prices. The same lodge owner told me he kept multiple sets of accounts to appease the authorities while keeping his business running.

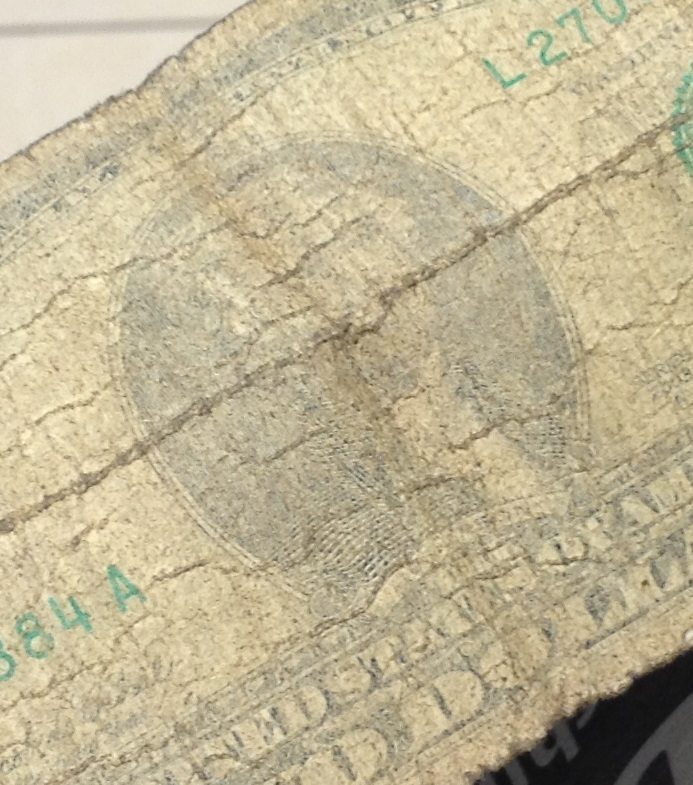

Maybe you’ve seen the Zimbabwean dollars from that time period. In 2009, Improbable Science awarded Gilbert Gono, the head of Zimbabwe’s Reserve Bank, with the IG Nobel in Mathematics. The prize is given for dubious accomplishments that make you laugh, then think. Gono won for “giving people a simple, everyday way to cope with a wide range of numbers – from very small to very big – by having his bank print bank notes with denominations ranging from one cent ($.01) to one hundred trillion dollars ($100,000,000,000,000.00). It’s a feat that won’t easily be matched for many years to come (or until Zimbabwe reintroduces the Zim dollar).

These dollars float around now as collectables, but if you look closely, you’ll realize that they aren’t collected for their design elements. With inflation rampaging out of control, these notes are often simply plain paper printed with a few numbers (many of them zeros) and a slapdash etching of a lake or a bird. At the nadir of economic collapse, the bank didn’t even bother to print bills on both sides, and why would you?

They were literally worth less than the paper on which they were printed.

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.