[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he latest exhibitions at the Zabludowicz Collection in north London explore how to make and present contemporary sculpture.

Four young artists are presented and their work each occupies a different room in the gallery spaces, which makes for an eclectic viewing experience. The Collection is known for showcasing emerging young artists and nurturing the latest talent in the UK and abroad, and this show certainly does by enabling interactions between new pieces for the exhibition and artworks from the private Collection.

[quote]although we are living in a world

of dematerialisated art, these exhibitions

are about materials, the physicality

of objects and bodies, and sculptural

making processes[/quote]

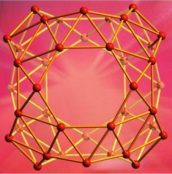

Although each exhibition has the potential to be a disparate experience, and the gallery as a whole to feel fragmented, the Zabludowicz Collection manages to hold them together through several common themes, some of which are more obvious than others. These themes include the evocation and exploration of the human body, the concern with states of change and the passing of time, and the use of everyday materials. The artworks are also in dialogue with the gallery’s environment.

Whilst the Zabludowicz Collection emphasises the medium of sculpture, the exhibitions are also about contemporary installation and even painting too. Blurring the distinctions between these genres can encourage a productive way of viewing the show. It helps to spark dialogue between different entities – whether this is in terms of media, environments or scale – and this seems to be important for these exhibitions and the work of the Collection itself.

The abandonment of hierarchical distinctions between artistic genres also helps to elevate the status of sculpture, which throughout its histories has struggled to find a steady position within the arts. Finally, the mixture of sculpture, painting and installation also adds to what curator Paul Luckraft stresses as the backbone of these exhibitions: the notion of “balance”, which can also include the balance of materials, ideas and forms.

Sam Falls, from the US, fills the first room in the Zabludowicz Collection with large-scale paintings and sculptures. This is a striking opening, and the artist’s canvases are some of the best works on display. They are each concerned with duration and natural processes, both in their subject matter and making process. This is because Falls worked outside on an island near Helsinki to create his paintings, encouraging leaves and flowers to fall onto the ink marks he had made. Over time, the canvas was also subjected to rain and wind, harnessing the natural elements and the processes of weathering to affect the canvases’ surface.

In a way, they are almost like ‘photograms’, using the effects of time and light to fix an image. With Falls’ paintings a lot more is left to chance, and this is what gives them their individual character. Using photography (whether it is the ‘idea’ of a photograph, a similar sort of ‘photographic’ process or photography as the backdrop or inspiration) is becoming popular in contemporary sculpture. This is a link that has often been overlooked and, remarkably, extends back to the late nineteenth century.

In stark contrast, Falls’ industrial sculptures stand assertively in the main hall of the gallery and look as though they would resist the elements completely. Their use of materials and sparse nature are obvious extensions of Minimalism. They further contrast the paintings because they were made and set up within the gallery space before being moved outside, whereas the paintings were made outside and are intended to be viewed in a gallery.

Brazilian artist Adriano Costa differs from the others in the show because he has combined a mixture of new and old work. He also moulds the sculptures to the particular room in which they are displayed in humorous and quirky ways. Objects appear in corners of the room, rising from skirting boards or fluttering from the walls. The largest object (a ladder) is hung between the floor and ceiling as though suspended in mid-air. Here, familiar objects that form part of our contemporary consumerist lives are defamiliarised and given subversive power.

In this way, the artist transforms everyday materials, and this is another theme that can be found throughout each of the exhibitions. It also suggests that this artist is playing with the boundary between ‘precious’ art and throwaway non-art objects. We are also asked to re-think the viewing experience of sculpture because Costa’s common objects appear flat; the viewer is often made to look down at a piece, which makes you wonder if it is actually sculpture you are looking at.

Michael E. Smith’s sculptures also respond to the Collection’s spaces in humorous ways. His sculptures are often located at partially hidden or overlooked places. Smith calls them “defensive” because they react to a place or a person.

Many of these works are made with organic matter, and scull shavings and birds’ feathers make startling appearances. They are found objects of an abject nature. The emphasis on organic matter is partly why they are the most bodily of the sculptures in the show: they explore the fragility of the human or animal body, as well as the body of society itself.

Samara Scott, the only UK based artist, uses plastic and digitalised materials to play with the browsing history of images. Some of her work uses abstracted photographs that are smeared onto walls with pungent toothpaste, and made into still-life scenes of excess that could be mistaken for advertisements. It is not just photographic images that are abstracted but also plastic objects that have been partially melted together to create a smooth top surface, looking similar to a low coffee table. Underneath these sculptures the remains of the objects protrude towards the floor, making a kind of relief collage. These objects are typical of Scott’s work, which centres on surface and colour and is interested in the lure of superficiality. Scott pushes these elements towards the grotesque in an attempt to move past seductive surfaces.

Feminism is something the artist has only recently started to address head on. This seems odd considering the subversive use of largely feminine materials that indicates a transformation of the domestic. Additionally, Scott trained as a designer, and incorporates craft processes that again have historical references to feminine, domestic practices.

Overall, these are unusual and playful exhibitions, and interesting alternatives to the contemporary sculpture exhibition currently at the Haywood Gallery (which deals primarily with the figure rather than the body in sculpture). Luckraft points out that although we are living in a world of dematerialisated art, these exhibitions are about materials, the physicality of objects and bodies, and sculptural making processes. He continues, stating the shows are “about slowing down – the slowing down of time in an image saturated world.”

So here at the Zabludowicz Collection, it is not just our perception of different media that is challenged, but also our relationships to time, scale, colour, form and materials. Luckraft hopes that with this, viewers will be excited and encouraged to think about “the multiplicity of sculptural practice today”.

Open Thursdays to Sundays 12 – 6pm, until 10th August.

[button link=”http://www.zabludowiczcollection.com/” newwindow=”yes”] Zabludowicz Collection[/button]

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby