[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]H[/dropcap]e Does The Police In Different Voices.

I was waiting for my partner to arrive on the steps leading down to the Barbican’s theatre and, as streams of people passed me, I strained to peer into each face to identify a familiar profile. Paying attention in this way makes everyone look familiar and you begin to question who each one really is. Were they like me – wondering who I was, whether they knew me?

Somehow when you’re standing in a crowd you’re adapting to how you might be perceived.

Neil Gaiman is speaking about all the stories that he has forgotten. He has made a joke earlier about his beard– that he had grown it in the hope of looking like someone who looks like a sincere allegory for ‘an academic’, at a talk he did at his old school. The beard was intended as a mask against the preconceptions of his past and yet, it is not the mask he wears tonight. Tonight his mask is one of a born performer. It gleams at the room. It is a loose mask, the kind of mask that doesn’t make you question whether the person beneath it is thinking about their interval drinks order. [quote]a short novella wherein the

beats of the intertwining narratives

feel cinematically choreographed[/quote]

It is a mask that says : ‘I am here. Beneath this, I am giving everything to being in this moment’. His face is as expressive as his melodious voice; it is also a mask that says ‘…and I am out there with you too’. You can feel the room catch its breath. And all that tension, all that longing, it’s there in Gaiman’s voice in all the stories that, though forgotten, are there bubbling beneath each exhalation.

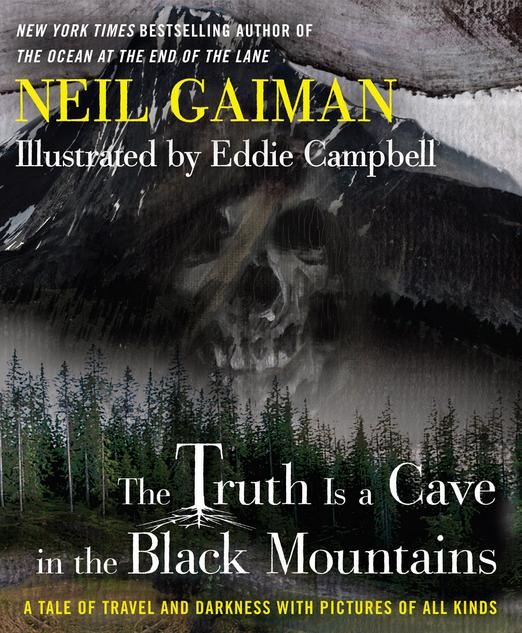

For it’s the stories that he is dedicated to. Whether it be the anecdotes about his wife posing naked in front of a Degas in a New York Gallery and (thankfully) remembered short stories penned from fans’ suggestions that populate the first half of the evening or, the main event– his reading of The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains; his is a gift for taking all those drifting voices and bundling them into one harmonious projection. Behind each story there is a sense that a hundred more have, are and will be told. Instead of questioning who each of us is Gaiman’s voice – which although it is distinctly his– never relinquishes its dedication to the storyteller, invites us to get collectively lost; to suspend time, to listen, to be alive, to be now.

His voice is much like the narrative of The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains, a short novella wherein the beats of the intertwining narratives feel cinematically choreographed. Rich with allusion to tales old and new, the divergent fable – set in Scotland long ago – shakes off any postmodern concerns over mediated experience and builds new paths from the buzz of the materials of the conversations that are within us and our cultural heritage.

To hear the words of the ‘wee man’, our narrator, feels like walking into the midst of an ongoing familiar conversation, even as we are enveloped by a world thick with mist, caves and porridge. Though concluded on the evening with a slightly inconsequential and awkwardly orchestrated half-book plug, half-Q&A led by Hayley Campbell, the echo of the story still rings strong and true.

[quote]No matter how fantastical the

imagery there is an underlying

human quality that makes his

stories eminently believable and

compelling[/quote]

Like all the best stories an ostensibly straightforward plot line is approached tangentially, so that it doubles back and reveals the layers of suggestive threads that it has enfolded you. It follows the journey of its small protagonist who employs a comparatively towering, rugged Reaver to guide him to a cave in the mountains, where lies as much gold as he who enters can carry. As with many morality tales the prize carries a price – a price which the narrator’s companion has himself, succumbed to in his youth. In this case the price is to sacrifice morality itself, leaving the victor rich but devoid of any notion of good or evil.

Though occasionally dropping a stitch in subtlety, Gaiman’s general talent for casually juxtaposing poetic arcs with an idiosyncratically dark, wry commentary pulls and stretches sentences into the realisation that the mysticism of the cave is within the characters themselves. It is a technique that colours all of Gaiman’s writing with a unique and distinctly modern magical-realist hue. No matter how fantastical the imagery there is an underlying human quality that makes his stories eminently believable and compelling.

Originally published in 2010, the first version of the performed piece was commissioned by The Sydney Opera House for which Eddie Campbell produced 50 accompanying illustrations. These now number over 100 and range from watercolour sketches, to lush vibrant oils to digital drawings incorporating real life photography. In their variance they brilliantly compliment the verbal mix of fantasy and candid realism, creating a filmic backdrop that enhances the rhythms of the narrative voices without detracting from the focus upon the evocative nature of the text.

Perhaps it is the conspicuous lack of ‘reading aloud’– in our Kindle-dominated time where books are something of a distraction and accessory rather than a quotidian public expression – in general, that imbues Gaiman’s words with such a lure. And yet, there is an intrinsic lyricism to the story itself – as if fired by the hallucinatory embers of a hundred campfires past – which hazes the point at which hearing and speaking begin and end. A body is conjured within the letters that demands to be inhabited, to be swung about and, to be voiced. We too are identified as a part of the telling and, it is Gaiman’s performance, in sync with FourPlay’s compositions that does not just demonstrate how to tell, but how to actively listen to these stories so that they beat within our hearts.

His dexterous handling of the text – which, when the musical score pauses, barely misses a pulse – impels us to travel, to channel the language through the passageways of our ears and to reach out to meet it. Flicking his eyes occasionally for cues from the musicians, he could almost be a fifth member of the quartet; though the music is never intrusive instead, like the illustrations, allowing the story to inhabit the milky limelight. Indeed, the strains of the earthy tones and ethereal vocals, beautifully evoke the Scottish setting and seem to, not only accompany, but to inhabit the words. The elision reverberates with a raw and primal energy, so akin to life, that to absorb the tale becomes, not a choice, but rather a matter of survival. Gripped by the story, we cannot help but hold on.

Neil Gaiman is a generous performer in the sense that, having entered into each story, he holds the door open – so that we might enter too. For an hour or so you feel you have become intimately acquainted with the man who builds an igloo out of books, the genie who has never realised that he is lonely, a battered wife and abusive husband cut off from the world on the hostile moors and, of course, our ‘wee man’.

As Gaiman shrugs awkwardly when he misses a cue from the band, the contrast with the power instilled in his incantatory voice, is brought into sharp focus. The intermediary pause is palpable with a rapt and ravenous curiosity to get back to the narrative and yet, it is precisely this modesty in the face of his craft and the wry dark humour that permeates his stories that lend them such a compelling edge.

Life and stories in Gaiman’s worlds are different forms of the same art and, together, they can inspire the same illusion; that you can really get to know another being – in all their awkwardness and absurdity – from another time, another place. For an hour or so, we could almost taste the wetted air of foggy heaths and breathe the scent of mythical caves.

[button link=” http://www.neilgaiman.com” newwindow=”yes”] Neil Gaiman[/button]