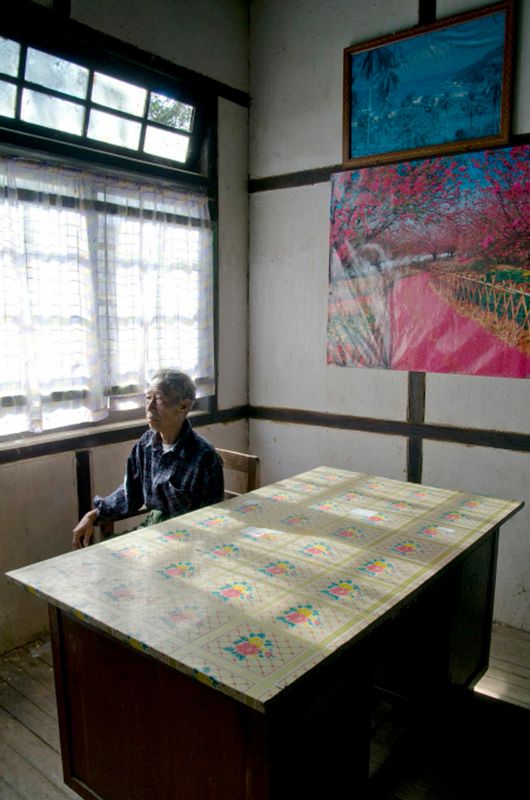

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]U Tue Mg[/dropcap] displays an amiable smile when he offers me a seat and a cup of sweet lapaye tea.

But he is naturally nervous, as I am. We can’t exchange more than half a dozen words, between my non-existent Burmese and his most basic English. But this gentle elderly man understands the purpose of my visit to this remote corner of his country, and he proves to be an excellent host, like most of his fellow compatriots.

He is the secretary of the Agricultural Co-op in the town of Katha, a long train ride, or up to two days upstream by boat, from the venerable city of Mandalay, immortalized by Kipling’s famous poem. The enterprise’s large warehouse, where peanut oil and other produce are processed and stored, lies across the yard from our shady verandah. Accommodation is thrown in with the job, so he is the sole inhabitant and caretaker of the building, which used to be the headquarters of the British Club. The old colonial enclave was the centre of the local Anglo-Indian expatriate community at the time of the Raj.

Burma had become part of the British Empire during the nineteenth century as a province of British India, and George Orwell (né Eric Blair) spent five years from 1922 to 1927 as a police officer in the Indian Imperial Police force in what is now Myanmar. It was his experience in this isolated outpost that inspired him to write his first novel, Burmese Days, first published eighty years ago. It is a story about the waning days of the Raj before World War II and one of the greatest denunciations of imperialism ever written, a powerful critique of the colonial mindset that underpinned the system.

‘They arrive now’, Mr. Mg reported, interrupting my tour of the old building, still in excellent condition, despite its age. He had invited me to attend the afternoon remedial Maths session for the local schoolchildren. The classroom was downstairs, in what it used to be the old billiards room, then out of bounds to ‘non-Europeans’.

A group of about thirty kids started to take their places and listened to the explanations of the tutors, hired by the local education authority to help them to catch up with their school curriculum.

It was a surreal scene, trying to imagine Orwell and his workmates playing snooker in the evenings and toasting the King with a glass of gin and tonic or Indian Pale Ale. It had been transformed to a couple of dozen tables full of eager youth and a teacher pointing to a big blackboard with Burmese numerals, drowned by the cacophony of young voices reciting their tables.

‘Tennis there’… my host rescues me from the smiles of the diligent kids to steer me out of the house to point me in the direction of the outbuildings and the tennis court, also featured in the novel and still in use, as a free facility, by the neighbours. I thanked him and head off, after taking a few shots of a middle age couple doing warming up exercises before their match. The court and the changing rooms are well maintained, though the surface betrays a few cracks.

I am both confused and impressed. I had come to Burma to follow the thread of a novel by one of the most influential English writers of the 20th century. My pre-conceived narrative was fairly simple: Orwell condemned in this book and all his later work the twin evils of imperialism and thought control. I was going to put his exposition in the context of the realities of modern day Myanmar. The Raj is long gone – the country achieved its independence in 1947 – but it has been subsequently substituted by one of the most vicious dictatorships on earth, in the name of Socialism.

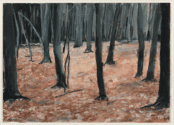

The destruction of the rain forest, started by the British and inferred in the novel (since some of the expatriates traded in timber) carries on at an alarming rate, although nowadays the main consumer is China, whose insatiable demand for raw materials fuels the deforestation of the countryside. I witness this at the harbour of ancient Mandalay, the second city in the country and the economic hub of upper Myanmar, where I went to photograph the constant loading of huge beams of teak unto boats of all sizes.

The precious cargo is heading up north, towards the Chinese border, before reaching its final destination inside Yunnan province on the Mekong River. A fat hardwood tycoon comes out of a fancy four wheel drive and challenges me:

‘Why some many pictures; you like my trees?’

‘Very nice trees’, I retorted, in total honesty. And, trying to buy time to get away without further trouble: ‘They will make beautiful houses’.

‘Oh, yes’, said the boss, evidently pleased with my compliment …’and look, more coming’. I turned to see another five lorries, weighed down with trunks, negotiating the dusty access to the terminal to wait for the next ship to dispose of their valuable haul.

China also controls the mining industry and is blighting the cities with hotels and shopping malls of the most dubious architectural taste. More importantly, the powerful neighbour is giving the ruling junta the political support they so desperately need, as they become increasingly isolated from the rest of the world.

The average Burmese continues to suffer from the greed of a neo-colonialist power; so little has changed in the last three quarters of a century.

Yet it is not easy to discover the ‘real’ Myanmar. I am travelling independently and have no official minders attached to me, though my whereabouts are obviously known to the authorities, since you are ‘logged-into’ the system from the time you buy a train ticket or book into a guest house.

But this is not necessarily the preamble to paranoia. On the contrary, wherever you go there is this warm sense of following a series of small serendipities, of being led to places and people who seem to have adjusted to the to and fro of history with peace and resignation.

Katha has a dreamlike air about it. The small town does not seem to have changed much since Orwell lived here. It has a fantastic setting high on a bank on a bend of the mighty Ayeyarwady – formerly Irrawaddy – River, Myanmar’s main artery, with views of distant mountain ranges.

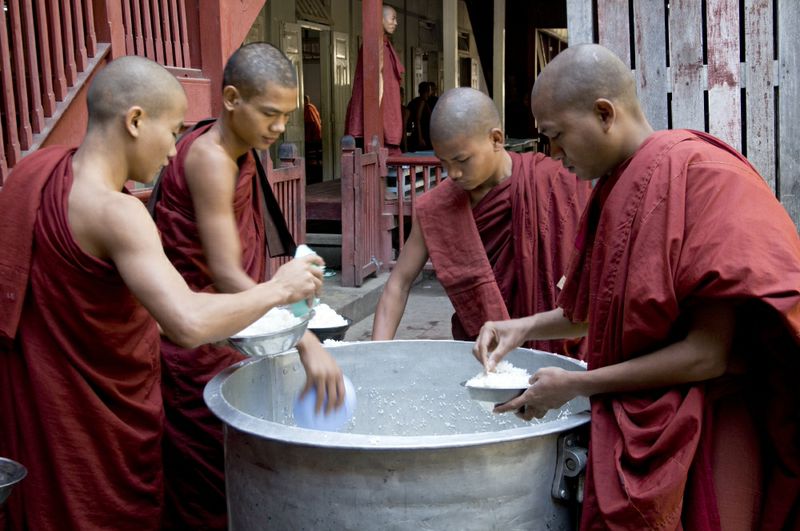

A number of Buddhist temples adorn the riverfront and I am moved to visit one of them on the far side of the main promenade. It turns out to be a monastery and the head monk greets me warmly and invites me to share their only meal of the day, taken around noon -heaps of rice and vegetables prepared by local people who take it in turns to cook for the monks -. We talk in French, which he learned in Laos during a long stay in the holy city of Luang Prabang. He is happy that the novices here don’t have the same temptations than the ones he mentored back there.

There is no Internet in Katha, so no chance for his young charges to get polluted with Google and Facebook, a favourite pastime for religious probationers in the rest of SE Asia, as I have witnessed on my visits to cyber-cafes in the region. The World Wide Web in Myanmar is confined to the main cities and even then, severely monitored by the authorities, with only selected websites made accessible. Since the monks have been at the forefront of the recent anti-government protests, I try to extract some comment on my host’s political views. But, alas, his remarks are oblique:

“Rien ça change ici en Katha…” which could be interpreted as a universal statement on the fate of any backwater, or as a profound analysis on the future of his troubled country, where the rulers won’t allow any dissent to flourish.

Satisfied with the rice and the blessings, I take a meandering path through a grove of fir trees to the site of another religious faith – St Paul’s Anglican church, which is one of only two Christian places of worship in town; the other is a catholic chapel. Although St Paul’s has been extensively rebuilt, it stands on the location where a crucial scene in Orwell’s book takes place. After a Sunday sermon, Flory, the central British character, is humiliated in front of the woman he loves, as part of an elaborate plot by a corrupt local magistrate to discredit him. As a result, she rejects him and he eventually commits suicide.

Through John Flory, a timber merchant who appreciates Burmese culture and becomes disillusioned with the Empire, Orwell portrays the first stages of his own personal transformation from a colonial policeman to a radical thinker.

It took me 15 hours of a very bumpy train journey to reach Katha from Mandalay.

I shared my sleeper compartment with three boisterous off-duty army officers who insisted in measuring out their ample supplies of food and local whisky with me. Unable to get any sleep, I joined them in an all night game of poker, ‘Las Vegas’ style, as they called it. Which meant, I ended up losing some 5,000 kyat, – about 5 US Dollars – but I guessed that paid for the roast chicken and the liquor. The only one of them who spoke any English, a captain in what he described as a ‘tactical unit’, told me about his exploits quashing the Karen insurgents, who have been fighting the central government in the east of the country, along the Thai border for more than three decades.

“I shot many enemies”, he boasted, emboldened by the firewater, “…and now we have peace in the Union of Myanmar”. It was a sobering moment and a reminder of the ruthlessness of a system that has consistently crushed the cry for autonomy or independence of the many ethnic minorities within its borders.

The company I kept on the train back to Mandalay could not have been more different: I was sharing a carriage with monks on their way to the capital, Yangon, as well as with a young family. It was inspiring to see the monks playing with the children and exchanging jokes with their parents. Members of Buddhist orders are venerated and deeply respected throughout Burma and ordinary people who come to help clean the buildings and feed their occupants visit their temples on a daily basis.

I wondered whether my fellow travelers had been involved in the protests that were brutally put down by the government a few years back. Human rights in Myanmar are a long-standing concern for the international community, although the situation has improved since the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

I visited many enchanting pagodas around the country. In the visitors centre of the main ones you always find photos of the ruling generals praying and paying their respects at the altars. Buddhists believe that you can partly expiate your sins by building or restoring temples. It reminds me of U PO Kyin, the corrupt magistrate in Burmese Days, who plots against Flory to himself become a member of the exclusive British Club.

He, too, believes he can get away with his wicked ways by financing new sanctuaries, but shortly after the unhappy expatriate takes his own life, Kyin dies, unredeemed, before building a single shrine.

Maybe the mysterious laws of karma, apparently understood by Orwell, will finally vindicate the inhabitants of this alluring land.

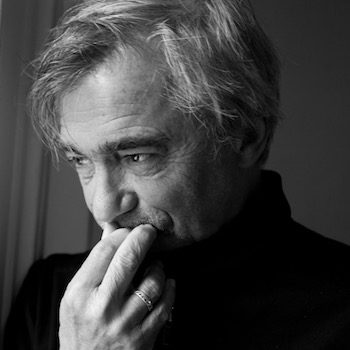

Words and pictures ©Julio Etchart

Julio Etchart’s Exhibition : Katha : In the Steps of George Orwell in Burma will be showing along with photographer Tom White and academic Dr. Li Yi: at Objectifs Gallery, Singapore as part of Burma: ‘The Golden Leaf’.

24th Oct – 15 Nov