[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t must have been the summer of 1995 when I had my mind blown in a field in Oxfordshire.

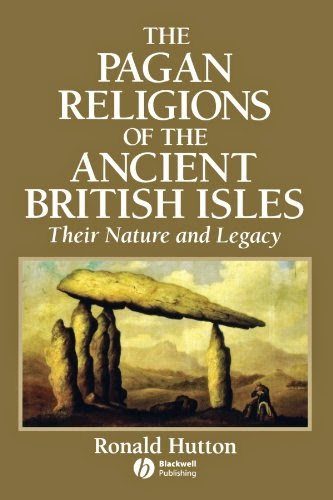

I was at the very first OBOD camp and went to a talk by the historian Ronald Hutton. In the space of forty minutes, and with his trademark élan and erudition, Ronald demolished every foundational belief of my naive paganism. I was left reeling with cognitive dissonance, and yet, come the end, I didn’t want him to stop. On my return home, I immediately bought and devoured his Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, a summary of the archaeological and historical evidence for what was then known about pre-Christian religions in Britain.

It’s possibly a universal human tendency to bend the past to our contemporary desires. We start with a theory, then cherry-pick the evidence to fit with how we want the world to be. Thus, throughout the twentieth century, all manner of evidence was assembled to support the Victorian idea that paganism was an ancient fertility religion, one with licentious and often heinous rites, and one that somehow persisted in secret against all odds and despite concerted efforts by Christianity to eradicate it.

This was what had made the idea of paganism so thrilling to me, though like most other pagans I thought the heinous rites bit a dreadful slur and chose to ignore that part of the story.

Hutton’s approach was so refreshing because he turned this approach on its head, assessing all the available evidence to find the most plausible interpretations, or being big enough to admit we don’t know in the many cases where the evidence was too equivocal. Under this kind of scrutiny the lurid Victorian view of paganism I’d inherited crumbled. The pre-Christian religions of Britain turn out to be far more rich, complex and nuanced than this simplistic story allows.

Published over twenty years ago, The Pagan Religions was well due a rewrite and that’s exactly what Hutton has done with his Pagan Britain. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

In this magisterial and interdisciplinary work, covering everything from the Ice Age to the Vikings, Hutton makes many of the same points as before but brings the evidence up-to-date. The chapter on ‘The Legacy of British Paganism’ justifies the cover price alone and is required reading for anyone interested in the subject. It’s all written in a far more accessible style than its academic-oriented predecessor, an acknowledgement of the fact that in the intervening period he’s garnered a keen, non-academic audience. To them his message is clear: within the generous limits imposed by the evidence you’re free to imagine the past how you like.

‘The Legacy of British Paganism’ justifies the cover price alone and is required reading for anyone interested in the subject. It’s all written in a far more accessible style than its academic-oriented predecessor, an acknowledgement of the fact that in the intervening period he’s garnered a keen, non-academic audience. To them his message is clear: within the generous limits imposed by the evidence you’re free to imagine the past how you like.

Interestingly, the two volumes have bookended my academic career. Back in the 90s, meeting Ronald heralded my return to academia. He encouraged me to embark on my second PhD and indeed ended up being my external examiner. I think his influence on my own work should be obvious and I remain extremely grateful to him.

Now, with our relocation to Dartmoor, I have left academia (never say never, though I can’t imagine returning) and I found on reading Pagan Britain that I am less interested than I was in defining the boundaries of what we know about the past, much more interested in dreaming up what lies in the gaps.

As I havered about doing a second PhD, Ronald’s advice was this: if you don’t like it, you can always go back to the fields.

I did like it, but the fields got me anyway.

A writer and a folk musician, Andy is the author of ‘Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom’ and has published a range of articles and academic papers on subjects as diverse as psychedelics, paganism, bardism, environmental protest, fairies, shamanism and evolution. A modern day troubadour, he plays mandolin, writes songs, and fronts darkly crafted folk band, Telling the Bees. A leading exponent of the English Bagpipes, he plays for brythonic dancing in a trio called Wod.