[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]s the Kiefer show ‘good’ or ‘bad’? Can we make such a judgement one way or the other?

Anselm Kiefer was born in Donaueschingen in 1945. To be born in Germany in the immediate aftermath of WWII was to bear the burden of a recent history in which you had played no part. The guilt over the atrocities of the Nazis was a crippling weight on the German conscience. A blanket cutting-off of all associations with the stain of that era was seen as the only route to purge a nation’s soul, and so Kiefer grew up in an education system too ashamed to even mention the war.

To emerge as an artist during this period was particularly problematic: Hitler himself had been a painter, and he had clear views on what ‘good’ art was, and its role. The Nazis shaped their identity around a particular rich history of German culture. Kiefer took up the challenge laid down by Joseph Beuys, who encouraged the next generation of artists to not ignore their history or Germany’s cultural heritage, but to engage with it and find healing in the confrontation.

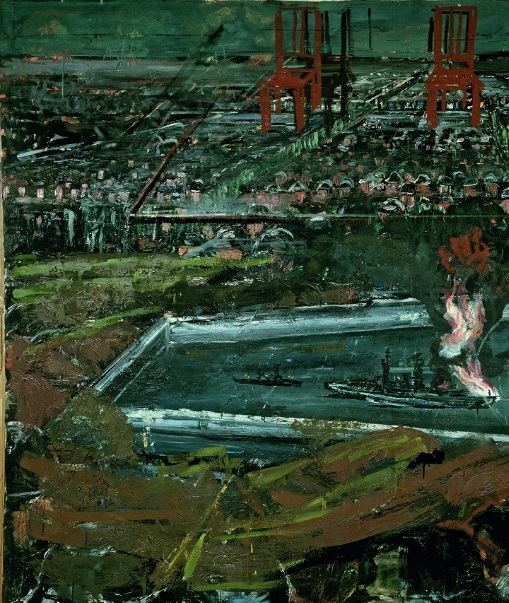

Anselm Kiefer Operation Sea Lion (Unternehmen Seelowe), 1975 Oil on canvas, 220 x 300 cm Collection of Irma and Norman Braman Miami Beach, Florida Photo Collection of Irma and Norman Braman, Miami Beach, Florida / © Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer Operation Sea Lion (Unternehmen Seelowe), 1975 Oil on canvas, 220 x 300 cm Collection of Irma and Norman Braman Miami Beach, Florida Photo Collection of Irma and Norman Braman, Miami Beach, Florida / © Anselm Kiefer

Dressed in his father’s army uniform, Kiefer staged a series of photographs at various locations (from his studio and home through to iconic venues and landscapes) in which he is seen making the Nazi salute. He made paintings based on these photographs. The salute had been banned in Germany since 1945, and outrage over Kiefer’s work led to some critics going as far as to label him a neo-Nazi. This absurd form of visual blindness was, paradoxically, exactly the reason that artists like Kiefer felt the need to aggressively confront what they had been told to forget.

Casper David Frierich’s ‘The Wanderer’ was one of the most iconic paintings from the German Romantic tradition. It was a tradition the Nazis happily appropriated in one of the greatest of art heists, stealing the gems from German art history and re-situating them to promote the values of the Nazi state. The Nazis had a very clear idea of what good art was, both in terms of taste and morality. There was a kind of state sanctioned neo-classicism.

Hitler had trained as a painter prior to entering politics. Art, he said, should not ‘wallow in filth for filths sake’. In 1937 the Nazis presented an exhibition of seized artwork that they labelled as degenerate. The aim of the show was to illustrate the poisonous nature of Modernism and Expressionism.

Kiefer conflates these various visual references, mixing the iconography of the Nazi’s salute and German Romanticism with a crude expressiveness, and a conscious ugliness that would have been at home in the exhibition of degenerate art. It is as if he is not only taking back the German history the Nazis stole, but also taking a central piece of their iconography and mockingly dressing it up in the ‘filth’ of ugly painting.

They are consciously bad paintings in aesthetic terms, but patently good painting in terms of artistic and moral worth. These early works feel like statements of intent, aggressive markers for a history that has haunted Kiefer’s career, and a grappling of identity that lies at the centre of his practice.

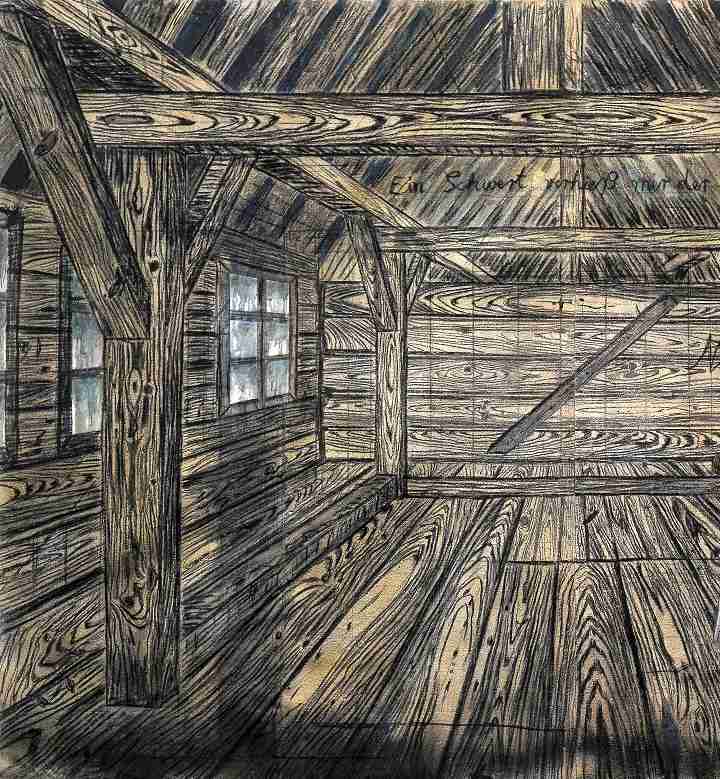

These ghosts are present in his attic paintings. In Nothung (1973), we stand in front of an attic space, wood-paneled from floor to ceiling. A ceremonial battle sword is plunged into the floor. The sword has been cut from cardboard and stuck directly onto the painting, crudely and with no intent to hide its separation. It asserts itself as literally lifted; sliced from one place and put into another – exactly what Kiefer has done in both physical and metaphorical terms. The Nazis aligned themselves to certain Nordic myths, in a form of cultural imperialism that looked to build narrative and iconographic models of heroism, and to promote the nobility their battles. Kiefer takes up the sword, looking to reclaim the grail, to rehouse it in the safe space of the attic – both of his studio and within his painting. He is saying ‘this is mine now, not theirs’. It is the plunging of a flag into new ground, but it is the flag, rather than the ground, that is the territory at stake.

Anselm Kiefer Nothung, 1973 Charcoal and oil on burlap with inserted charcoal drawing on cardboard, 300.5 x 435.5 x 4 cm Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photo Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photography Studio Tromp, Rotterdam © Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer Nothung, 1973 Charcoal and oil on burlap with inserted charcoal drawing on cardboard, 300.5 x 435.5 x 4 cm Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photo Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photography Studio Tromp, Rotterdam © Anselm Kiefer

It is useful to think of the attic in the context of Bachelard’s ‘The Poetics of Space’. The house is seen as a body of rooms, each carrying certain psychoanalytical – Jungian –weight. The attic speaks of the entire structure of the house, and thus of rationality and safety, of what is known. The basement, conversely, is seen as the dark recess of uncertainty and the irrational, a container of monsters and darkness. We might read Kiefer’s swords as grails found in the shadows and horror of the basement, which he has ripped from those nightmares and plunged into the safe, known terra firma of the attic.

The attic paintings are large, and feel like spaces we can walk straight into, as though Kiefer is inviting us in. Their configuration is much akin to neo-classical History paintings. In David’s ‘Oath of the Horatii’ for instance, space is very clearly, geometrically formed: frontal and symmetrical, positioning us at the frontier of the fourth wall. Such a space is constructed and then populated with figures in action, and consequentially with narrative. Kiefer gives us just the space and the sword. In ‘Oath of the Horatii’ a father holds three swords aloft, presenting them ceremonially to his sons, readying them for battle. Kiefer does the same. He plants the sword in the ground, calling us to battle. He calls on us to activate the scene, to take up the mantle and to form our narratives. Symbols cannot be owned, the paintings suggest, merely borrowed. Meaning is never absolute, but always awaiting new life, new contexts and new players.

In the 1980s, the suffocating intensity of some of Kiefer’s interiors is replaced with a breadth of landscape paintings. The tradition is broadly an expressive form of Romanticism: the landscape as the sublime. When they work the sheer weight of matter and substance in the paintings seems to overwhelm, to consume and to have a power and poetry to them. In Ash Flower (1983-1997) the ludicrously long gestation of the painting seems present in its very surface. Kiefer unites the strength of his architectural interiors with the power of surfaces in his landscape paintings. The entire architecture of the space and the surface of the painting seem to be on the point of collapse, through the sheer weight of breaking, cracking paint. It is impossible to not look at this and think of the photographs of post war German cities, the type of urban spaces Kiefer had grown up in, in which ash covered skeletons of bombed houses were the climbing frames and playgrounds of his youth. It is a simple but powerful painting, full of rich technique, poetry and pathos. This is Kiefer at his awe inspiring best.

But they are not always successful. At their worst they feel dead, mere illustrations of feeling and thinking rather than instigators. The Order of the Night (1996) sees a figure prostrate on the floor beneath some looming sunflowers. It is Kiefer painting a bad Kiefer.

[quote]when Kiefer is at his best

we don’t need the leaden symbolism

of diamonds, not when the mud

and filth of paint can carry the

weight of time and gold[/quote]

Kiefer’s symbolism is complex and rich, although often repetitive. He has various large studios: one just outside Paris is a huge industrial warehouse, another in the South of France occupies an area of countryside the size of a small town. These spaces are often already pregnant with material and history, and then become populated by Kiefer. He builds tunnels, collects huge amounts of objects (some obsessively categorized and others piled chaotically into rooms). Entire architectural structures are built from piles of shipping containers. Whole planes are constructed and shifted into huge greenhouses. Rows of paintings line walls so long that studio assistants require bikes to travel from one end to the other. These spaces are Kiefer’s laboratories, places for him to create and destroy passages of new worlds and to manipulate materials and iconography in the hunt for new forms. The libraries are full of a wide range of reading matter, much of it esoteric. The history of his work becomes a fertile compost heap for new beginnings. Books are everywhere, including piles of books found in one studio that appear to have been rescued from destruction. These playgrounds are where Kiefer’s work emerges, labyrinthine spaces in which things can be lost and destroyed, or found and recreated.

Failure is a key tenant of this process, and it lies at the centre of a work commissioned for the RA show. A room is filled with a pile of discarded canvases, as if prepared for a bonfire. Rocks weigh the paintings down. Debris is scattered around. Sculpted sunflowers emerge around the pyramid. It is new life from old. It is a dominant, powerful sculpture: another statement of intent.

Kiefer sees history as non-linear, as a network of cyclical connections woven together in a web-like matrix. For him, history is the grand sweep of geological time frames, not the brief window of remembered or written human history. There is clearly a depth and integrity to his thinking and feeling over this, and at its best seems to drive the work forward and to be infused into its being. At his worst it seems like faux philosophy, either in the form of trite ‘poetic’ soundbites, or projected loosely onto his paintings. This intellectual and emotional integrity is his strength but also, when it becomes too earnest and unfiltered, his weakness.

Much of his thinking seems to emerge from a potpourri of writings, with mysticism and alchemy often central. He explores the line between corporeal and ethereal realms, finding particular interest in the ability of art to turn base matter to gold. Sometimes this is present in the work in quite literal ways – he often uses lead and exposes it to a variety of chemical process to oxidize and age it. Kiefer is interested in finding processes that either accelerate the course of time, or that transform matter, shifting it to a higher state.

Tàpies, an artist with a similar spread of interests, is at his best when he manages to make the sheer weight of his materials seem to rise or float. Kiefer is at his best when the sheer weight of his materials seems to make solid gravity, and to condense time. They both look to shift matter in opposite directions, and both fail when the matter seems to sit flat and solid on ground, in no way denying itself. Both artists look to enact alchemy on their materials, in the sense of matter transforming. To study alchemy is to study the art of constant failure in the search for the moments of magic. There were a handful of paintings encrusted with diamonds, which were humorless and unconscious pastiches, as crass as Hirst at his recent worst. No amount of critical blather can hide the cynicism of these paintings, everything about which screams that they are made for the gauche, inflated belly of the art market’s worst excesses. Which is a shame, because when Kiefer is at his best we don’t need the leaden symbolism of diamonds, not when the mud and filth of paint can carry the weight of time and gold.

Anselm Kiefer Osiris and Isis (Osiris und Isis), 1985-87

Anselm Kiefer Osiris and Isis (Osiris und Isis), 1985-87

Oil and acrylic emulsion with additional three-dimensional media, 381 x 560.07 x 16.51 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchase through a gift of Jean Stein by exchange, the Mrs. Paul L. Wattis Fund, and the Doris and Donald Fisher Fund. Photo San Francisco Museum of Modern Art / © Anselm Kiefer

The penultimate room of the exhibition is filled with recent large-scale canvases depicting fields of sunflowers. It is a motif that runs through Kiefer’s career: rich tributes to Van Gogh. The sunflowers are nearly always dead, symbols of the legacy of history, which holds seeds in its husk ready to scatter the triggers for rebirth. This is what these paintings are about, the process of the new coming from old. Not all the paintings in this room work, which is because they are trying something complex. They are looking for that moment between chaos and order, when forms shift and emerge from surface. It is the moment anyone who paints searches for, to find the charged moments in the medium and the canvas, and to hold it there. At least three of the sunflower canvases are knockout – all amorphous forms, exciting passages of paint either holding onto or reaching for articulation. Perhaps we might push Kiefer’s geological timeframe further, to the birth of all life, when the universe first presented matter to us, and all time and all life was in that initial chaos. There is something of that process and of that magnitude in the sunflower paintings. They are odes to Autumn and a homage to history, time and painting, presented as epic visual poems. The canvases that don’t work are interesting but slightly mannered paintings, lifeless and empty of magnitude. On the surface so little differentiates them formally, but in that small gap is a sweep of meaning and feeling beyond comprehension.

Which leads to the episode of Imagine hosted by Alan Yentobb made to coincide with the show. It was beautifully filmed, capturing in particular the majesty and scale of Richter’s studios, and the sheer energy and scale of ambition of his creative energy. Yet the whole thing was fawning and sycophantic. Everyone interviewed and involved in the program and the show was in awe of Kiefer. It felt like one big advert. He gave some fascinating insights and is clearly a sincere man and a deep thinker. But he was also allowed to get away with pompous cliché and trite statements disguised as poetic intellectualism without ever being challenged or pushed. The program would have us believe that the cult of the artistic genius still lives on, as if everything that Kiefer excretes is artwork of the highest order. He spoke about how nothing is ugly, and referred to an Indian beach where the mass of shit from thousands of different people was a hymn to this fact, with the sheer range of colour and surfaces. That all filth can be gold is of huge importance to his work, but sometimes shit is shit, and it stinks.

Perhaps it is market forces. Kiefer’s work sells for millions of pounds, and huge favours at great costs will have been called in, in order to facilitate the scale of the RA show. A collector who forked out millions on Kiefer, in the belief it is both a work of the highest order and a sound investment, might not take too kindly to the suggestion that some of his work isn’t great. Which is a shame, because Kiefer is a great artist and the RA show is a powerful show. It is full of amazingly compelling paintings, which forced me to look with intensity, to think deeply and which moved me significantly. But some of the paintings lack power, and are stilted and boring. The empty and blanket praise for the Kiefer show would seem to suggest the institutional forces now at play have crudely decided we can just categorize him as good on aesthetic, philosophical and moral grounds. The truth of his work, and of his life and history, is far more complex and rich than such lazy binary judgements suggest.

To acknowledge this variety is merely to acknowledge how difficult it is to make great art. To deny it is to allow commerce and marketing, ironically, to reduce and simplify the scale of the successes.

Anselm Kiefer is on show at the Royal Academy of Arts, London until December 14th.

Sidebar image: www.freedigitalphotos.net/Simon Howden

[button link=”https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/” newwindow=”yes”] Royal Academy of Arts[/button]