Italian artist Luciano Perna’s solo exhibition, Psiche, at Marian Goodman Gallery features a series of eighteen colour photographs of objects and landscapes, each captured through flashes of lights against cavernous black.

Perhaps, it’s human tendency to anthropomorphise, to want (or need) to locate ourselves in what we see, but there is a mood in these works that seems to strike a chord with pandemic fatigue, and the general peculiarity of contemporary existence. This is especially the case with Perna’s photographs of drooping flowers and spiky potted plants. April 22, 2020, 6:46, for example, a flattened, sagging, spidery, monstrous, blooming plant, appears positioned on a pedestal draped in black fabric, the drama intensified by the light, illuminating the spine of leaves and casting shadows. It’s theatrical, and silent, dangerous and domestic; the very image of our daily lives, in confinement, the unbearable atmosphere of impending doom entangled in micro-dramas and suppressed emotions.

Of course, flowers have long been a subject of art and photography, and we view the work not only through our personal encounters but also through the shimmering gauze of all the previous representations that we’ve encountered. In a recent essay on Perna’s work, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh wrote, ‘every image of a flower projects the desire for an instant gratification, if not a reunion with an imaginary origin and wholeness, and every photograph annuls that very desire by decisively fracturing access to nature’s figments.’

Perna’s still lifes appear in isolation, in blackness, sometimes completely untethered as if floating up from the depths of our psyche (psiche is the italian word for psyche which stems from the ancient Greek psukhḗ, meaning soul or breath); ‘our’ psyche rather than his because there is a strong universal quality to the objects that he’s selected. We know and can name the things we’re seeing, even if they’re detached from their contexts.

Cosmonaut Glove and Seashell is one of the most intriguing images – not because of the objects’ obvious disparities, but because of their similarities. Positioned side by side, we notice their likeness through texture and colour; the glove could easily be a calcified formation from the sea. It’s a beautiful image, but it also bears the ominous foreshadowing of human extinction just as the drooping plants evoke the increasing precarity of the natural world.

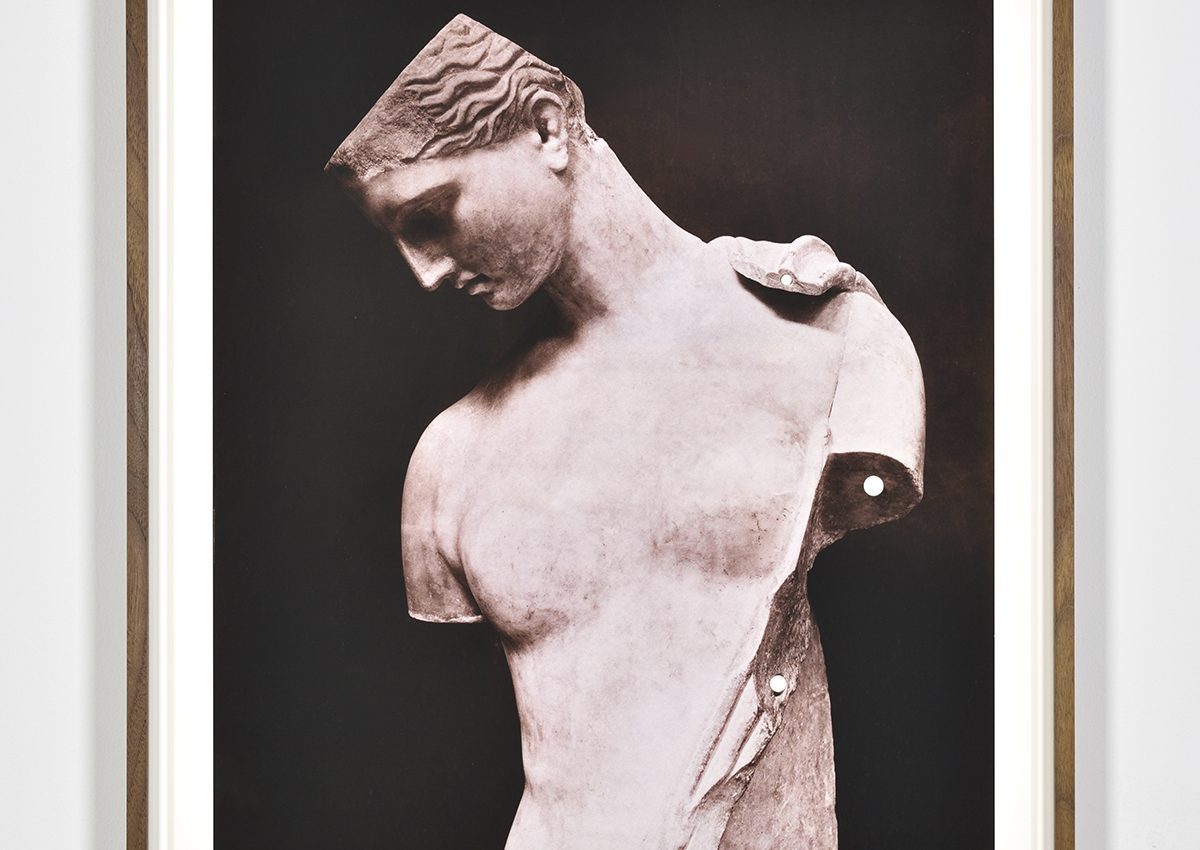

Images such as Psiche 2020 depict sculptural objects taken from the museums of Naples, Perna’s birthplace, and possess a pervading sense of nostalgia but also detachment. The sculpture in Psiche appears severed at the limbs; a mutilated corpse, from a long-ago era, a memento mori. This relates also to the artist’s choice of medium – the literal flattening of an object through the printed image, but also its enshrinement. Perhaps, then, this collection of work is an attempt at suspending time, clutching at the flimsy edges of experiences and memories, giving them shape through blaring light.

‘Luciano Perna: Psciche’ is available to view online: mariangoodman.com

Featured Image: Luciano Perna, Psiche, 2020. Photo by Rebecca Fanuele. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Copyright Luciano Perna and Marian Goodman Gallery Paris

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.