I absolutely insist that you have a look at this painting.

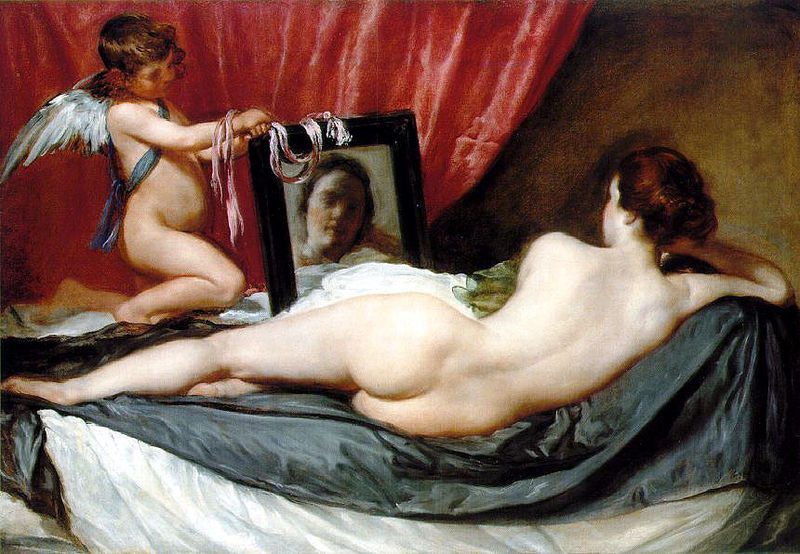

This beautiful glorious nude, Venus, the symbol of female beauty and sexuality, reclining, with her beautiful back, and that grabbable arse.

Lying, not in an ornate setting, but on a couch with a few sheets, with her reflection – ambiguous in terms of identifying the model, but staring directly at you. Not passive, but active in its engagement with you. Cupid, holds the plain mirror, the only allusion to the idea that this was a woman from mythology.

Not an explicit painting, but a painting which leaves you in no doubt that this glorious woman is there for sex. No fearful waiting, no timidity. Just a woman, a beautiful woman, in possession of her own sexuality, not as an object for someone else, but invested in what is happening. The face of the woman’s reflection blurred, so it could be any woman, but the directness of the gaze, unmistakable.

This ‘British treasure’ is not really called ‘The Rokeby Venus’. It is ‘Venus at Her Mirror’, painted by Diego Velazquez, a painter to the Spanish Royal Court around the middle of the seventeenth century. Britain ‘acquired’ it, during the Napoleonic wars, and its common name comes from the house in which it was displayed.

Velazquez painted his Venus at a time when the very sight of the naked female form, was ‘dangerous’. Spain was, and still is in many ways, a country where natural expressions of sexuality were quashed by the dogma of the Inquisition of the Catholic Church. Where a woman expressing sexual desire was guilty of sins which would damn her mortal soul, and demand her exclusion from society. The sight of her body a danger to anyone who saw it.

It is a shame that the only way this painting could have come into creation was as a commission for the King of Spain to ‘view privately’. I had an argument once with a friend who believed that the painting was nothing more than early porn.

This painting was commissioned for the private enjoyment of a very powerful man, himself an architect of a society where women’s sexuality was so sinful that it needed to be repressed. The repression of female sexuality, which has formed the basis of our morality for centuries, ensured that this painting could only be commissioned, or viewed, as an expression of something shameful and hidden. My friend was partially right.

Look at the painting itself though, this painting is as damning a response to the millennia long repression of normal female sexuality as I have ever seen. This painting may have come into creation for the private pleasure of men who didn’t care to follow the rules they set for the rest of society, but it is not pornographic.

Velazquez’s painting, created at a time when any threat to Catholic sexual dogma would carry a real risk to life and liberty – is nothing less than an absolute challenge to all those beliefs, and nothing less than a celebration of all women, and of sex.

When Mary Richardson, a young militant suffragette, slashed the painting in 1914 while it hung in the national gallery (in her own words, she had ‘tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs.Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history‘) – the British public were outraged.

She was vilified by the media as a mad woman for attacking this ‘national treasure’. The nickname ‘Slasher Mary’ was hers – a name which would not suggest to me, that this was someone who had vandalised a picture.

Mary Richardson was not a mindless zealot. The ‘national treasure” that she vandalised was so ‘dangerous’, that The National Gallery were following strict guidelines for its display, trying to avoid causing permanent damage to the morality of those who viewed it. Young women especially, would surely be corrupted by exposure to such an honest image of their own sexuality. This picture was a very clear symbol of the oppression of women, not through the intention of the artist, but through a society which turned it into something shameful. All the while, queues of people turned up to see the painting, in the very hope that it would somehow ‘corrupt’ them.

In the midst of this hypocrisy, it was ignored that Mary Richardson was part of a wider struggle. A struggle for the right to enfranchisement, in a society where women were truly denied power, and felt the effects of this powerlessness. Mary Richardson got on her bicycle, and went to The National Gallery to slash the picture in protest of the brutal treatment of a very real Emmeline Pankhurst. Sylvia Pankhurst, in her statement about the direct action of the Suffragettes, showed that she not only knew the painting, but knew it well enough to state that she didn’t really think it should be attributed to Velasquez. The painting was chosen BECAUSE of what it represented, and it is somewhat ironic that of all people, it was those who vandalised it, who understood it.

Through the story of the ‘Rokeby Venus’ we see the entire history of the ‘women’s rights’ movement.

Attitudes to women and sex still lag far behind what we see expressed so beautifully in Velazquez’s painting. We see this in debates about reproductive health services, contraception, and rape. But even four hundred years ago, there were people who could see past that. This image, this beautiful, unashamed view of a woman’s body was created, and even under the weight of the Inquisition and centuries of artificial sexual morality and repression, it survives.

When I go to The National Gallery to view this painting, I can see faintly the scars of the slashes that Mary Richardson left. The remarkable restoration of this painting means that Mary Richardson’s ‘vandalism’, has become part of the story this painting tells, not something which detracts from its beauty.

She is not the most famous of the Suffragettes, her actions brought her little more than national humiliation and vilification. She is only one of hundreds and thousands of women throughout history who have been willing to stand up and fight for the right of women to be allowed to exist as they are, and to be treated equally.

When I see this painting by Velazquez, I know that the ‘ideas’ that women like Mary Richardson fought for, are not new.