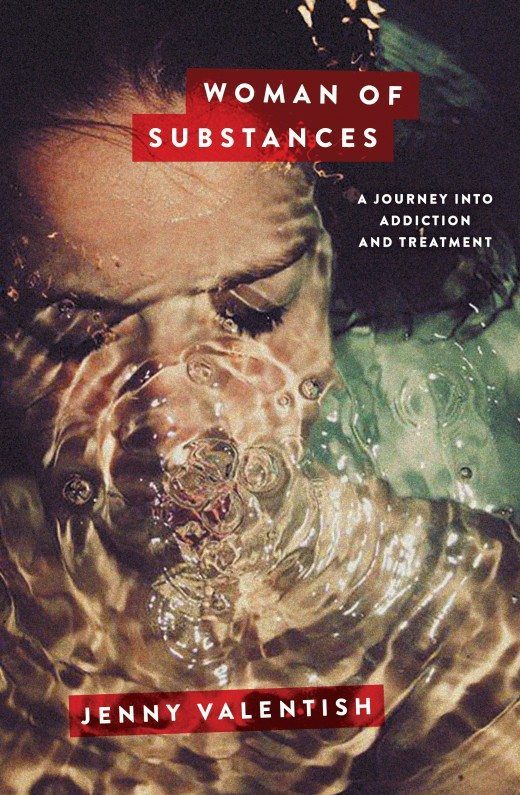

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]J[/dropcap]enny Valentish’s first nonfiction book Woman of Substances is part memoir, part in-depth investigative journalism about how alcohol and drug addiction and recovery are entirely different experiences for women.

While her research is mainly about addiction treatment in Australia – where she moved from England in 2006 – her point that much still needs to be done to help female addicts applies to medical establishments everywhere.

“The kind of issues that might contribute to a woman’s dependence on substances – more so than for a man – include shame and stigma; relationship problems; fear of losing children or a partner; lack of services for women, particularly those with children; and physical and sexual abuse,”

Valentish writes. “To that I can add post-traumatic stress disorder, which in substance-using populations is five times higher than in the general population.”

One of the events that started the addiction cycle for Valentish, not to mention for a staggering percentage of women with substance abuse problems (one professional is quoted as saying 70% to 99.9%), was sexual abuse by an older boy when she was around seven, a trauma she suppressed for years. She began getting drunk on a daily basis at 13, sneaking drinks from her father’s liquor cabinet at home in Slough. Alcohol initiated her into a masculine subculture where she enjoyed her status as a self-described “boy’s girl,” her internalized misogyny constantly reminding her – in the pre-riot grrrl era – that she had been born on the losing team.

Valentish found her way into drug culture in her later teens through friends she met through the penfriend sections of British music magazines like Kerrang! and NME, as well as through older male musicians. She includes a fascinating run-down of the little-discussed social hierarchy of drug circles, with men controlling the access and flow of drugs and women enjoying very little importance.

At 17 she wrote the hilarious and brilliantly subversive zine Slapper: The Groupie’s Guide to Gropable Bands, only to be excoriated in the Sunday Observer by the NME journalist she had contacted with her work in the hopes that he would become her mentor. Despite this setback she went on to become a successful music journalist and editor in Australia.

Her narrative becomes slightly disjointed at times, woven as it is in a non-linear storyline throughout facts, statistics, and interviews with researchers and addiction treatment specialists, who explain concepts like why some people are so bad at emotional self-regulation. But her writing style is consistently darkly funny and brutally honest: “Like many rejected, disenfranchised girls, I gravitated toward older men the way that rejected, disenfranchised boys gravitate towards the IRA or ISIS.”

The most useful section of the book for any reader struggling with addiction is the spot-on, outspoken week-by-week description of her first year of sobriety at age 34. She pulls no punches about the hormonal rollercoaster, mood swings, inexplicable acne outbreaks, weird periods, fatigue, appetite changes, beastly PMS/PMT, sugar cravings, and other physical and psychological symptoms she suffered as her body regained its equilibrium.

“If you thought you were a bit nuts before, now you’re nuts with the volume turned up,” she says. Basic information like this is harder to come by outside rehab centers than one might think, as is the kind of excellent advice she provides in the chapter Choose Your Own Adventure, such as “Hack your reward system” and “Set your own sobriety agenda.”

Her unflinching descriptions of new bad habits popping up as coping mechanisms after she stopped drinking – energy drinks, coffee, nicotine, Candy Crush, cold and flu tablets, an eating disorder, sexting, and porn – are a welcome change from the flowery, New Age epiphanies that addiction memoirs too often feature. Her take on Alcoholics Anonymous meetings is one of the best since the AA scene in Infinite Jest. She fortunately stumbles upon a women-only group, avoiding “13th Stepping” attempts by old-timers in mixed gender meetings (see Steve Jones’ recent autobiography Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol about his unparalleled skill at 13th Stepping) to pick up women new to the program.

By the end of the book it is clear that she leans toward the sensible UK and Australian therapeutic model of harm minimization rather than the puritanical 12 Step all-or-nothing definition of sobriety.

Valentish writes, “Addiction isn’t gender neutral, and neither is mental health. If this isn’t reflected in research, treatment and policy, then a huge chunk of the intended demographic will not receive appropriate support.” Woman of Substances might well be a much-needed call to arms for improved services for women struggling with substance abuse.