[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]B[/dropcap]enedict Drew presents his first major exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, The Trickle-Down Syndrome, conveniently in time with upcoming political change, or perhaps stagnation, in the United Kingdom.

The title of the exhibition makes reference to the trickle-down economic theory, which suggests investing on the wealthiest sections of society would also be beneficial to lower classes, as wealth ‘trickles down’, eventually resulting in collective improvement. Through this varied experimental installation, Drew calls into question the practicality of this concept, which evidently fails to function.

The exhibition explores what does trickle down, if not wealth, and whether all sections of society affect each other mutually, rather than accepting an exclusively downwards influence.

The entrance piece is visually impacting as film, sound, and painting are combined to represent a hive mind, thick black lines spreading off the edges of the walls and into the floor. The sound emitted by the television blends in with sounds throughout the exhibition, creating an immediate sense of curiosity and disorientation. Vibrant colours are constant throughout, creating a sensory journey.

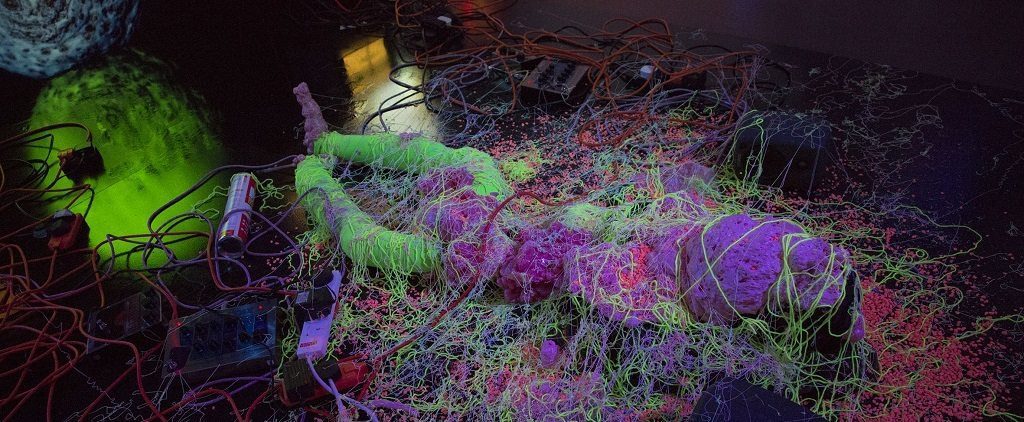

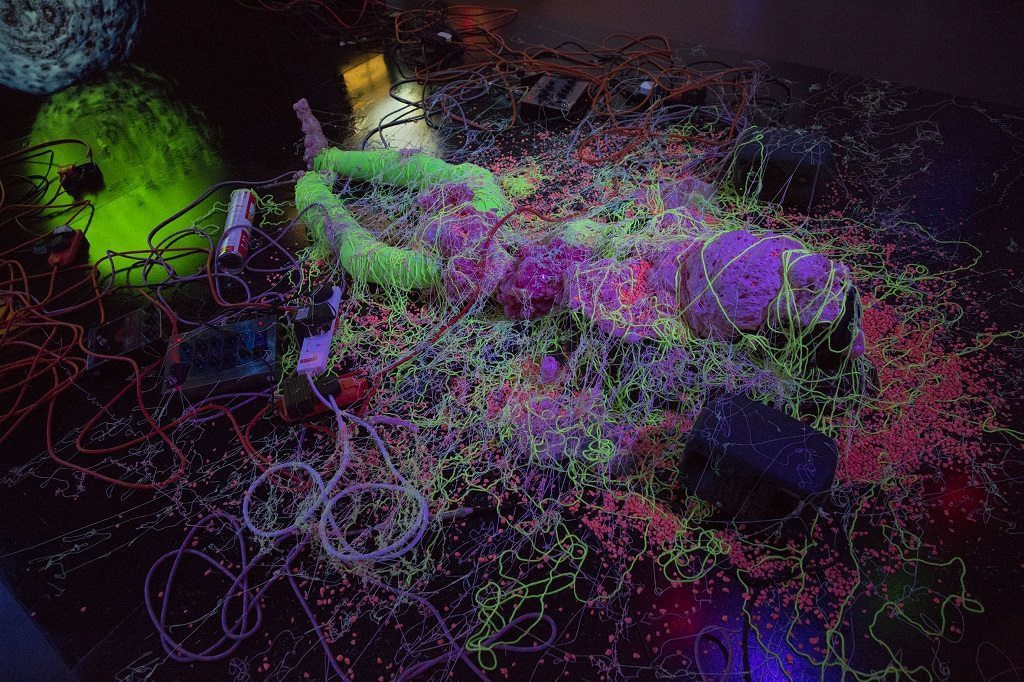

Our mood changes in each five connected spaces, progressively fading out of excitement and into unnerving discomfort. Large wall prints of wormlike drains or intestines hang on pipes on both sides of main room which at the centre holds the largest piece; the shrine.

Drew’s interest in the messy human quality is given emphasis through the handmade objects on the shrine. Papier mache eyeballs with broken strips of tin foil leap out towards the viewer amongst a series of televisions simultaneously reproducing a collage of film and kaleidoscopic colour.

Black and white cables are openly displayed on the surface; no effort has been made to hide the construction of the installation. The amount of cables, which seems almost too much for the number of televisions and speakers in the piece, again reveals the interconnectivity of peoples through media and technology; the invisible net is metaphorically exposed.

The perfection that is expected from digital art today, particularly with minimalist clean-looking works, is counteracted with the imperfectly playful sculptures and paintings. The golden gong at the centre of the installation creates a ritualistic atmosphere which, side by side with the televisions, suggest an almost religious tribute to the media.

A section of the film shows us a man struggling to crawl through thick mud draws us back to the questionable residue the drips down. The title of Drew’s LP Crawling Through Tory Slime, which is being released concurrently with the exhibition, enhances the visual concept as symbolic for the entrapment of lower classes. The answer of what trickles down seems to be a thick layer of slime that holds everyone in place; the drip tray at the bottom gathering the greasy fat from the upper-class’s juicy meat.

Mud reappears on film in the final section of the exhibition, comprising of a television surrounded by red screens. Although the final two spaces of the exhibition reenforce ideas raised in the prior sections of the show, they seem underwhelming after the visually overpowering installation. The overarching political theme is at points muddled between the flashy uses of colour and materials, making us wonder whether an overwhelmingly sensorial journey is the best approach in order to convey a particular message.

Nevertheless, Drew’s sometimes ambiguous stance pushes the viewer to negotiate between their own beliefs and sentiments.

Benedict Drew’s work contrasts starkly with the ISelf Collection and A Handful of Dust exhibitions currently being displayed at the Whitechapel gallery. His work takes a more playful and experimental approach, putting sensory stimulation before neatness of presentation or the conveyance of a clear message.

Until September 10th at Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Images:

Born in Barcelona and based in London, Anna writes about art, techno and psychogeography. She is also a lover of film photography and is slowly building an Olympus camera collection.