Sour-Puss, a quasi-autobiographical character created by Diogo Duarte and Jessica Mitchell, presents a ‘fantasy coming out story’. A collaboration presented in its entirety with this book, it provides a Gesamtkunstwerk that delves into unresolved sexual identity and feelings of anxiety in being one’s true self.

Bonding over a mutual dislike of ‘toxic positivity’, Duarte was drawn to photographing the ‘playful and experimental’ Mitchell. Five years later, Sour-Puss has evolved into a book now published by GOST and draws together various parts of their partnership including photographs, drawings, and writing by the artists and curator Anna McNay. Whilst at times a clash of styles prevents a cohesive sense of what the ‘Sour-Puss’ character is, the dynamic between the two artists nevertheless creates a compelling and surprisingly beautiful assemblage of material.

The collaboration is anchored by Duarte’s image-making. He uses light combined with a movement of the character between settings to develop a narrative surrounding Sour-Puss’s coming out. Tellingly the book starts and ends with a photo of the same setting and Sour Puss’ journey is described by the differences. Both show Sour-Puss at a restaurant table, but between the two they have emerged from the inside to the outside, moved from a dark space to a light, and shed a stiff buttoned-up shirt for a vest. Diogo gives us a literal ‘coming out’ that illustrates the journey of their character. However this is not overly trite, in both photographs, the character obscures their eyes indicating remaining traces of introspection and isolation. Essentially, Duarte is able to show the character’s progression without removing the sourness.

Because these images feel as though they could be self-portraits we can wonder about the dynamic of a man photographing a woman when the topic is around gender, sexuality and identity. In the book, both have made clear their reluctance to frame their images within the ‘male gaze’. Mitchell emphasises she has worked with ‘this man’ rather than ‘a man’ whilst Duarte dwells on not knowing what ‘masculinity means’ to him. Mitchell’s position is one of collaborator rather than muse. It never feels as though the camera is exploiting her, a testament to the equality and intimacy of this working relationship.

Mitchell’s drawings play at an attempt to give Sour-Puss a voice, but there is an inescapable autobiographical note to them. Colourful, crude female figures, often integrated with text fill pages and surround the book’s essays. They provide us with thoughts on the relationship between model and photographer, fertility, self-doubt and sexuality. A touching image features a smiley face surrounded by the words ‘I’m in a museum’ repeated over and over, mirroring Mitchell’s writing about how her younger self would be ‘proud and amazed at the photographs hanging of her on gallery walls.

While these drawings are emotive and visually engaging, they expose the problems with this collection. There is no meaningful integration between the photographic and drawn works. Whilst clearly a conscious choice to preserve the photographic narrative, their lack of integration does Mitchell’s drawings a disservice. At points, they feel relegated to decorations, part of the book’s design rather than the strong work they are in and of themselves. Allowing them space to interact and speak to one another would have emphasised their role as Sour-Puss’s thoughts and given depth to the characters experience.

.

Essays by the artists and curator Anna McNay provide a wider context to the creation and execution of the work, however this overly pedagogical explanation hinders the viewer’s own meaning-making. Mitchell and Duarte focus on their relationship and experiences of creating Sour-Puss. In the perspective of an autobiographical body of work the writings act as an additional string to the bow, becoming part of, rather than an addition to, the artwork. The problems emerge in McNay’s essay, which, while well written and insightful, acts as a contradiction to Mitchell’s emphasis on viewer interpretation. Both essays touch on the recurring ‘green stain’ that appears throughout the series, but while the artists leave meaning open McNay imposes meaning onto it. This is her job and she does it well, but including it here imposes an overarching meaning that no doubt influences the looker in their interpretations. It would have been a better and braver decision to bypass the academic essay and leave the interpretation up to the thus empowered viewer .

What next for Sour-Puss? Duarte has in passing expressed his desire to translate the work into an actual opera but thus far that’s talk rather than reality. They are both fairly definitive that they are done taking pictures of Sour-Puss so it does seem this could be the end. If it is, the collaboration is well served bound together here where the strands of writing, drawings and photographs are brought beautifully together. While problems regarding the integration between media stick at points, the essence of the cross-gender, cross-generational friendship succeeds. The project has allowed each artist to challenge one another’s perceptions and produce an insightful journey into self-acceptance.

Sour-Puss: The Opera, by Diogo Duarte & Jessica Mitchell, is published by GOST Books and is available now.

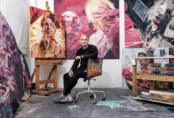

Main Image: Diogo Duarte, Sour-Puss: The Opera, GOST Books, 2021.

Ruth O’Sullivan is a writer and curator. Her work explores the impact of digital technologies on contemporary art practices and challenging gender disparity within the visual arts.