Jordan Ann Craig teases the infinite from the historic in her thunderous solo exhibition, though how did she get to displaying contemporary reworks of traditional Northern Cheyenne design in London?

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Craig has a deep connection with her Northern Cheyenne heritage. Since graduating from Dartmouth College with a BA, Craig has produced an impressive portfolio of paintings, prints, collages, textile prints, and artist books. Accruing seventeen awards and eleven international residencies came quickly to Craig, though staying true to her roots by representing the woman of Northern Cheyenne is still unfinished business. Subsequent to Craig’s first solo London exhibition Your Wildest Dreams, Trebuchet spoke with the up and coming Northern Cheyenne artist about space, time, practice, environment, identity and the conceptual mirroring of these in her October Gallery works.

“So Chilli was introduced to my work, the director in New Mexico. I happened to be in Europe while she was in New Mexico, but we made a meeting happen, lunch at October Gallery. I was here doing the residency in East London, it’s a really nice place, they got to me when I was there. Chile and I met a lot of the staff and got a sense of the community, the ambience, everything. That was impressive! It was amazing and felt so nice, and the lunch was so nice so we stayed in contact, and about a year later I was included in a group show called Portal Two.

That’s a long time ago, back when everyone had a life, right?

Right. It was before the shutdown, we went back in December. It was an exciting opening, I had five paintings in the show that took up the largest wall in the gallery so people really responded to my work, especially because they were being viewed in person. We had that group show and it was successful. Overall, a beautiful show with a bunch of really impressive artists. I went to a Bridget Riley exhibition with Elizabeth, who’s also the Creative Director and Curator here at October Gallery. She’s been here for a very long time, we went to go see the Bridget Riley session together which was a huge retrospective of Bridget Riley’s work. Elizabeth and I were really taken by it, by these huge geometric patterns. Anyway, on the way back I said cheekily, ‘Oh, it would be really cool if I came out back to London, and I made work here, you wouldn’t even have to ship it and we can do a show,’. I’m pleased I came back.

I imagine it must have been hard having the exhibition postponed. Did it have an impact on your practice?

When COVID hit, yes. It was hard enough to even paint, let alone plan an exhibition. It was so unclear, but the gallery honoured the plan even though I couldn’t make work here, I made the work in Santa Fe. The gallery has a lot of connections in Santa Fe so it felt right, we continued with the show, and now we’re here. A lot was happening in a greater context, we were having the Black Lives Matter protest, we had the fires in California. There were just so many things that were very heavy, the president, a president change, everything was just happening so intensely. It felt as if little old me, young me, in my studio, wasn’t a high priority. I felt making paintings was all about me, but when I tried to be a very active listener, that time was important.

Why was being an active listener important?

Being an active listener made me a better artist, since naturally I’m a very visual person, listening is not my forte. That being said, it is important to stop what you’re doing and listen to what the world needs. And at that moment it didn’t need me to listen, though that was in very early 2020, it was hard to get off the couch it was a weird time to think about anything. We’ve been scared to go to the grocery store, and toilet paper was running out. You didn’t have that issue, people were going crazy in America. People were getting aggressive and spitting on each other, it was absurd what was happening in the greater context, so it was really important for me to step back. I could make work that I could think about, work pertinent to what was happening. My little sister Bailey is my artist assistant and she told what you’re doing is important. She kind of picked me up off the couch and we made 14 paintings together.

Is this exhibition largely the COVID output?

Yes. And now everything has kind of changed a little bit, we had a lot of friends that already worked at home. And for me, I already work at home, I’m a painter, I work in my studio. Oh and a printmaker! I don’t go to communal printmaking studios anymore, but Alex, back to your original question. When you asked if all this work from that time, well it is. But, it’s newer, it’s my second body of work in the Roanoke Times during the pandemic. It’s all these besides one painting which was made from summer to fall.

I have two quotes from the exhibition, ‘I was hit by 1000 arrows, and I died happily!’ The second is ‘Jordan’s work is very precise, but there is poetry to it,’. What do you think about these quotes?

They are nice quotes, I feel it gives my work breath and heart, as if alive. They’re so precise and digitally rendered, almost rigid, almost! I’ve been called rigid before by an artist critique, I love that word now. Thank you, Brian. My sister was joking when we went out and said Jordan’s uptight, and then the guy said I’ve seen her art. Obviously, she’s uptight. And I know, but I take it with flattery because these are so precise. And you have to be a certain type of person to be able to execute this work. It is very precise, it is very constrained. You could say these are critical words, but I find them complementary. They’re challenging and they’re precise, it takes a lot of effort to make them so precise. So saying that they also have poetry to them, that’s a comment on precision. I would recognize the poetry quote as that they have something in them that makes them point beyond their precision.

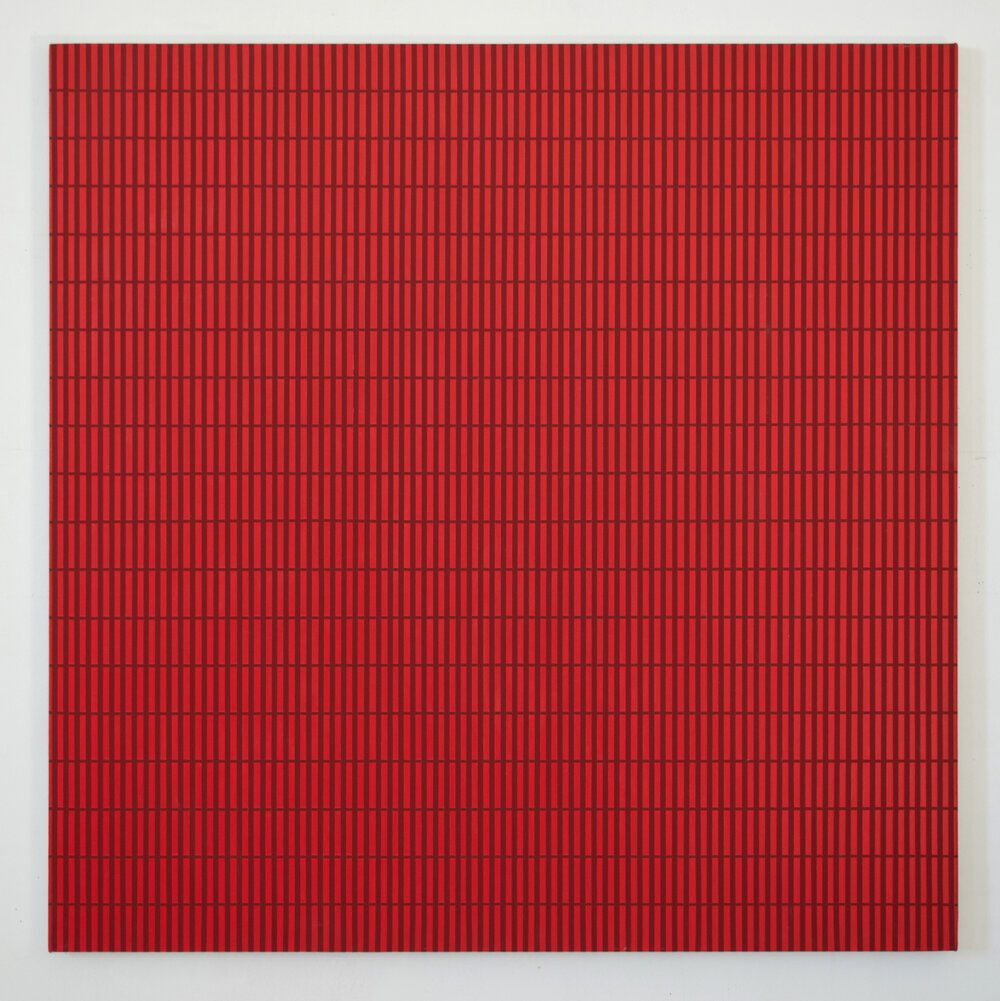

Are you influenced by fractal geometry?

I love the idea of wallpaper, I use a repetitive pattern that can go anywhere and expand to any size. These are kind of little glimpses of that, the thing about them, though, that makes them not so infinite, is I’ve placed them within a border. Or I have formed their structure very carefully, it’s all considered, everything from the density of the pattern to where the edge heads, to the colours on the edge, to how it gets framed. That’s all very thought out. That being said, they can go on forever, but I have put them into a box in a certain way.

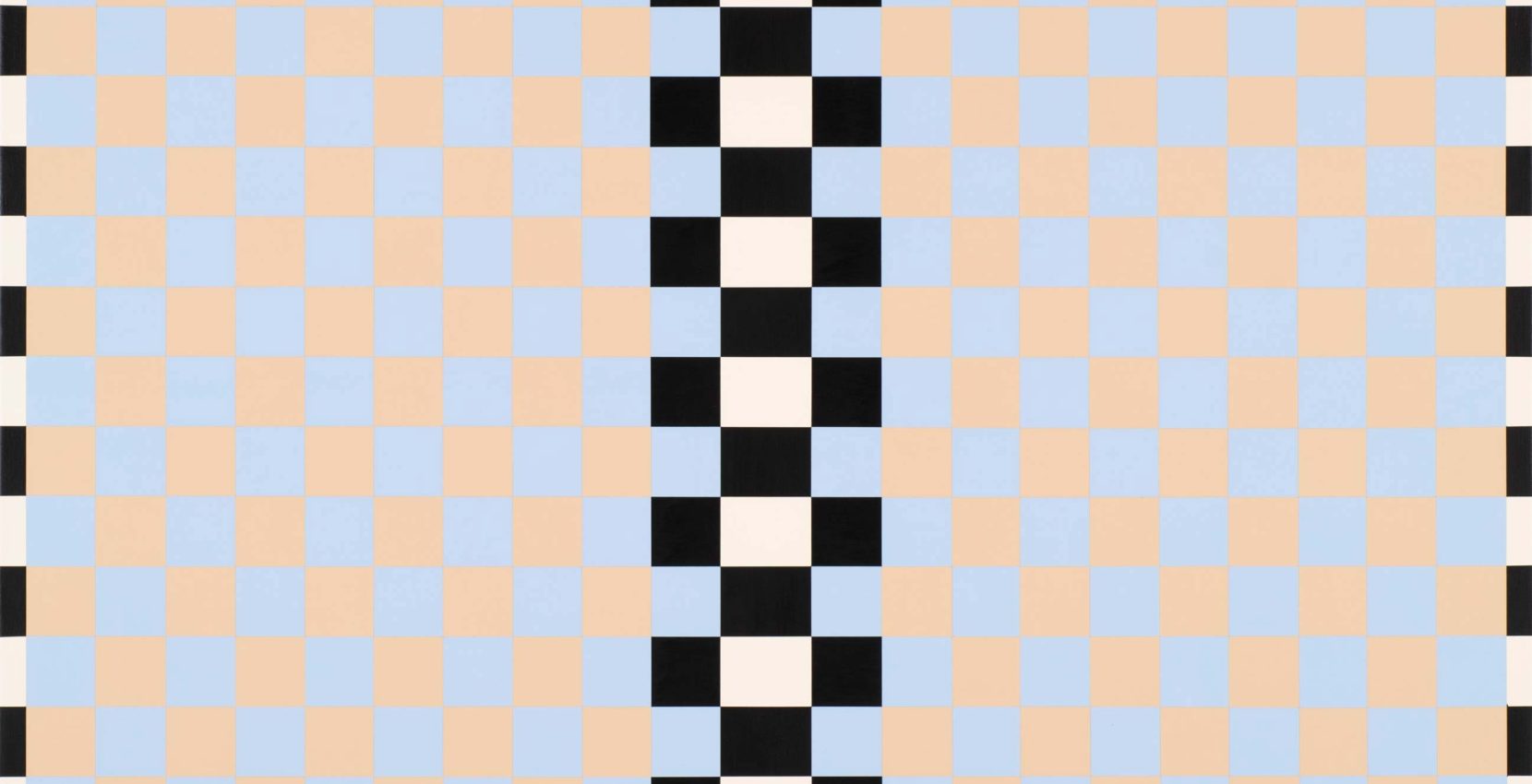

In Let’s Do That Again you use different shades of brown, and then you sandwich it with white and black, opposite ends of the spectrum. I thought that was really interesting.

Thank you, I’m always playing with colour, in that painting in particular with warm and cool. And then also dark lights, I use colour a lot when playing with the background. Brown is so cool and dusty. Oh, and green! Gold centres are really warm and rich, through playing with optical illusions I make some colours pop and some colours recede. These are quite flat, but they do something, they are pushing and pulling because of colour. And also because of the patterns, but the colour does play a big role in making this painting successful.

Can you tell me a bit about your piece Always Playing Games?

That piece is originally based on a Cheyenne moccasin. You will see this checkerboard pattern quite prevalently amongst Cheyenne designs, you’ll see it in a lot on moccasins, pouches and whatnot. During lockdown I saw it in fashion. It sounds ridiculous but the checker design became popular and trendy and all of a sudden it was in. People wanted checkerboard home goods, checkerboard tablecloths, even checkerboard pants became the thing. It’s a never ending fad, it comes out on repeat. I was seeing all these checkers everywhere and I wanted to be trendy, why not, right? When I started seeing these moccasins I thought wow, we’ve been doing this way before Gen Z. We had checker designs before millennials, you know my mum grew up with this pattern, and her mum grew up with this pattern, it just comes and goes.

Is it possible to verbalize the process of making a design?

I’m a printmaker, so everything is about the process to a certain extent. These paintings are very particular, I first start off by studying from different collections in person, contemporary and older pieces, and these are all based on Cheyenne beadwork and quillwork. I first start off by just looking untill I find something that I’m intrigued by, in this case I started seeing the checker pattern, so I honed in. And then I use Adobe Photoshop to make what was a three dimensional object with beads into a very flat two dimensional aesthetical pattern painting piece. I build it from there, it’s kind of a puzzle, and I have to put it together and figure out what feels right. Then I look at colours, the composition and how it fits on my square or rectangle. I want to figure out how it should feel, what I’m feeling. In this case, I saw the checker design, and I got an eye for a lot of these patterns which are divided with a centre pattern. It seems as if you’re interacting with a chessboard, that’s where these paintings are coming together conceptually, as well as visually. After I’ve completed the digital design, I know exactly how the painting will look, and then it just becomes execution. I have to prep my canvas first, and make sure it’s smooth and ready to receive the paint, then I build up the painting as it becomes another puzzle.

Do you need to make sure that you’re ready to put the paint on?

It takes a lot of labour and concentration. I have to be physically, emotionally and mentally ready to take on a painting, especially a gridded painting where it’s very arduous. I can get nervous sometimes, but once I’m ready to paint I feel excited, I have to want to paint it because it’s so much work. I was excited to paint because I had never made something similar. It’s very unique and it does stand out as a more unique painting in this show.

What makes Always Playing Games stand out?

The triangle border is a big feature, I started becoming more focused on the borders as opposed to the borderless infinite ones. That changed in this body of work, predominantly in Crying Over Spilled Wine. I made a border for the first time but many pouches and beaded pieces have a border, there is a signal that is also a sign, and a border. That started being reflected in my pieces. Instead of these aerial views or imminent patterns, I wanted to start constraining the pieces to see the definitive outcomes of having a border. It feels different.

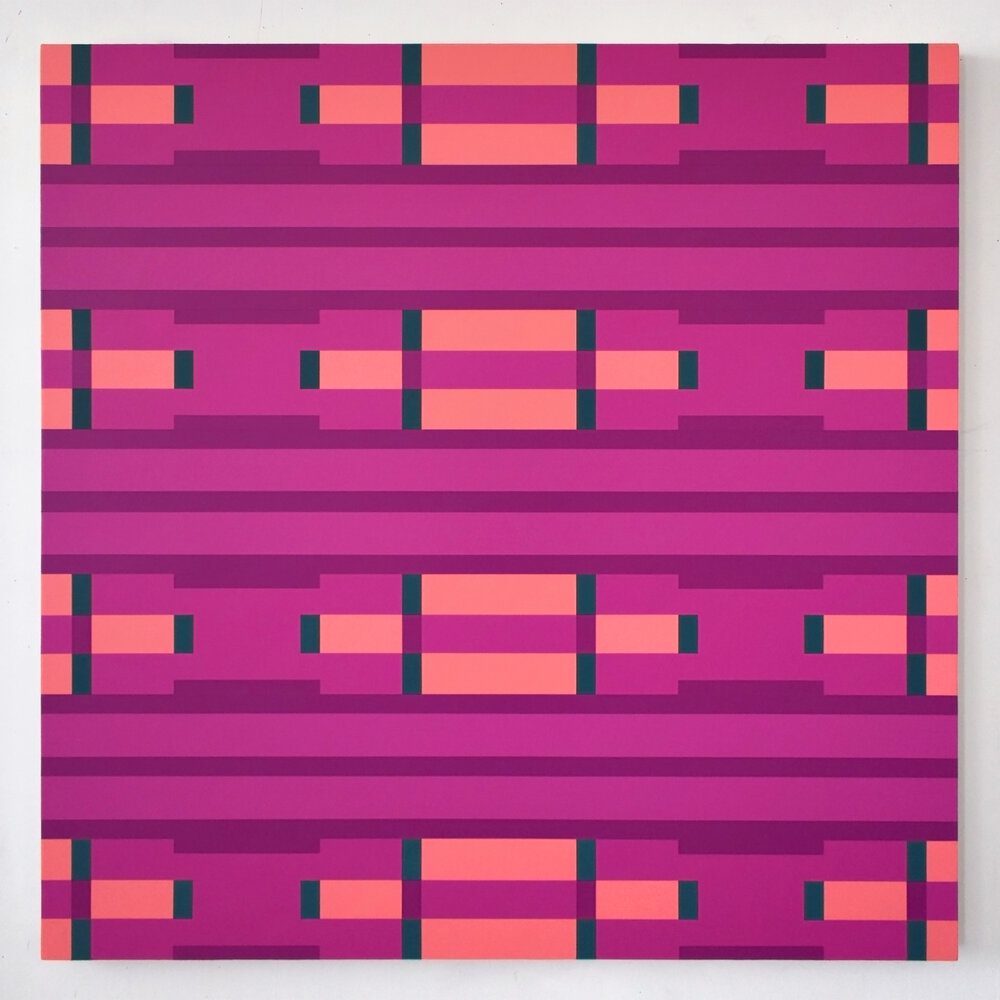

You were saying that Moth to Light, Baby came out of frustration?

The designing phase is the hardest part because that’s envisioning the work. Moth to Light, Baby was definitely made out of frustration, I made the painting in a much better mindset. Over a year later I saw it in my archives of designs and thought it’s nice, I’m going to paint it. It makes perfect sense because this piece, the original, got worked into the show. This painting was fixed in a panic, the other one was created in a panic but then painted in a very relaxed way. It was very easy to paint, everything went so smooth, it was different. I designed that out of frustration, She Got Work Done was an exploration. I sculpted it and it came together, some designs move a lot easier than others.

Moth to Light, Baby and She Got Work Done, are they the same pattern?

Everything has changed a little bit, but yes. I had to paint over this little line because it got chipped and I couldn’t fix it, I didn’t have the original paint to fix it so I had to cover the marks in She Got Work Done to salvage it. Not once do I expose them because I wasn’t fixing it, I wanted to keep the original intact, and these are the ghosts of the process. It covers so much paint, It was such a different looking painting before these were white. They were cream coloured and then I added these shapes because I had a big scrape. There are some remnants, you can kind of see it. If you scrape it then you stay away for an hour though.

What do you think of the Japanese philosophy wabi-sabi? Where imperfections are regarded as possessing beauty?

A lot of tribes, in textiles, leave a place for the pattern to escape. The pattern is perfectly enclosed and it’s a perfect textile. But they’ll leave one thing, a little opening which is a life line in and out. There’s something about it, is that it the same thing? Maybe not quite but you have this perfect textile, and then you’ll notice there’s a little line that goes off the border, it’s kind of like a path so it can keep being alive. Most of my paintings are pretty darn good, but I see all the mistakes.

I’ve read that to the Northern Cheyenne the environment is very important spiritually and is represented with geometric shapes. Is that something that you tried to do?

All of these shapes are rooted in the environment, in a meaningful place, in your home or in your community. When you’re wearing these patterns, it signifies what tribe you’re from, what family you are from, what your status is, it presents a picture of who you are. A lot of these shapes are found in nature and are incredibly important to the survival and the success of the Northern Cheyenne, rooted in nature and in Mother Earth. On top of that, there is my twist on things, so these paintings are influenced by where I am when I make them. A few of the pieces here were made in Wyoming and I can feel the colour is different, the feeling is a little different. I’m the same person, using the same exact tools, colours, paints, everything, but it feels different when I make them in different places. Santa Fe has a unique light as everyone talks about, so when I was there I looked at the colours, and also emotionally where I was at. After that I feel it’s two things, it’s the historical tradition and the patterns themselves. Where the patterns come from, the beads, and the work that went into that, and then it’s mixed with my experience.

Can you explain that a bit more?

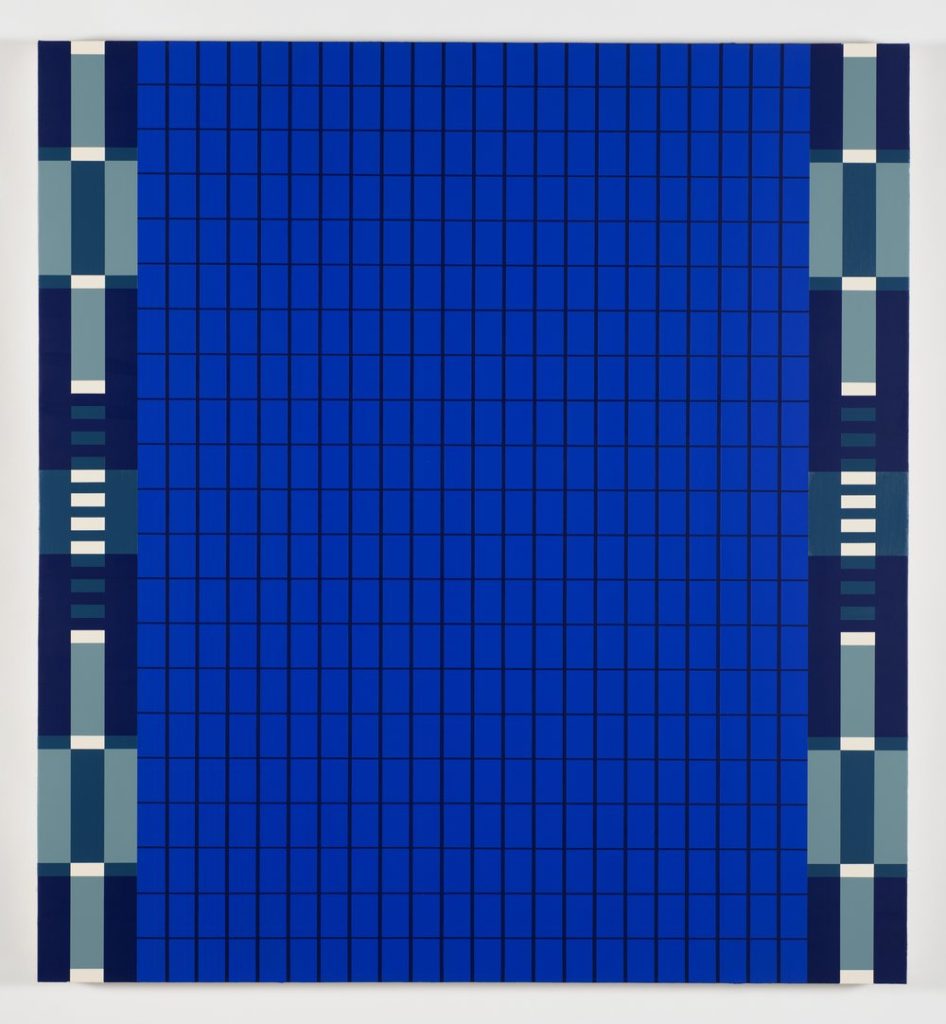

Sure, for instance when I mixed that blue for Baby, You’re So Blue, I used a baby blue. I already knew the title and I knew I wanted a baby blue painting. It was on a misty morning when I mixed the colour based on the sky, which I wanted to do but also didn’t want to do, because it could have been too blue and saturated. This colour is the sky of New Mexico, from playing in the planes, but when I saw that it was an early bright sky. It was unique and I wanted to match the colour to the sky, the same sky that I was looking at.

I’d like to ask you about existence, time, space, epiphany and cultural memory. These are your main conceptual influences. What do you want to tell the world about your art?

A few people hinted at it at the opening last night, that my work needs to be seen. More native women need to be in the spotlight, to celebrate them, to celebrate us. So the world knows that we’re here, we’re making work, we’re making beautiful things, we’re making big things and doing political things. We’re doing good and we’re doing good work, and it needs to be recognized which is why the show is important. The time and space and place we’re in, and bringing the work out of America and out of my studio into this big city, to be seen by a lot of people and to be recognized. It shows a different part, a different look at what it means to be a native person which I think is really important.

View Jordan’s portfolio: www.jordananncraig.com

JORDAN ANN CRAIG: YOUR WILDEST DREAMS, 2 December 2021 – 29 January 2022, October Gallery London.

Read Trebuchet article on her exhibition here.

Main Image: Jordan Ann Craig, Always Playing Games, 2021