[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]W[/dropcap]hy do drawings matter?

Commenting on his education as an artist at The Slade School of Fine Art in the seventies, restaurant critic, tv presenter, foreign correspondent, novelist, and sometime Call My Bluff panellist, A. A. Gill writes,

[T]eaching art, as opposed to teaching drawing and painting, is empirically counter-intuitive, almost an oxymoron, an impossible thing. With all the other arts you teach style and inspiration through technique, like learning to play an instrument is the way to learn music. But the last 100 years of the visual arts have been dedicated to extracting the art from the craft, leaving technique aside to set creation free. So rote teaching of skills can stifle, even strangle, creation (…)

Art and craft are obviously related and it would be a fool’s errand to try to categorically untangle them. But it is a salutary aesthetic truth that too much skill will make bad art (…) (Gill 2016, 76-7)

The nineteen seventies

In the seventies, we were at the backend of Modernism, with some schools of painting still attached to Clement Greenberg’s conception of abstract expressionism, its emphasis upon the flatness of the canvas, and the pure form of the painting, rather than representational content. Painting was all that mattered. No need for drawings.

The Conceptualists rejected Greenberg and his whole idea of formalist aesthetics. What they wanted was social content. Since social content can be delivered via newspapers and newsreels, it seemed that no amount of specific traditional skills training could deliver what art needed, hence the position that Gill mentions – back in the seventies.

It was in 1972, in response to the work with which Conceptualists were involved, that Oxford Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition entitled simply, [Drawing].

As an overview of many of the practitioners associated with minimal, conceptual, process and land art, [Drawing] put forward a case for the centrality of drawing within an era often characterised by the departure of both artistic skill and the physical art object (the oft-entangled ideas of deskilling and dematerialisation). (Straine 2018, 15)

The current exhibition

The current exhibition, the first at Drawing Room’s new premises since its removal from Bermondsey, is a collaboration with Modern Art Oxford – the latest incarnation of Oxford MOMA. It is an exhibition that focuses attention upon drawings.

Again, the concern is with the centrality of drawing. However, the curation has moved on to consider the activity of making drawings within the context of digital imagery and its ubiquitous presence in our lives.

Image manipulation software litters city streets with high-colour glossy nightclub flyers, pizza joint advertisements with gooey cheese stretching between the slice being lifted and the remaining pizza; and even images of saints advertising church breakfast clubs. The television bombards us with images of beautiful people in family settings or scantily-clad on beaches; or taking important decisions in board rooms; or driving sleek new German motorcars.

How can fine art drawings survive such a world? How can they continue to make themselves seen? Digital imagery has been appropriated by the fine arts and is used to further conceptualist ambitions; where the craft is far less important than the intellectual content.

Fine art drawings in the image flow

To sustain the pictorial in art – against what conceptual photo-collagist John Stezaker has called the image flow – the pictorial must engage the spectator. (Winters 2018) That engagement must call upon the spectator to grasp the presence of the ‘making’ of the image, as opposed to the ease and immediacy of the technology that threatens it.

The painstaking, absorbed, concentration of the act of drawing must offer the spectator an experience she regards as more valuable, in and of itself.

What the spectator sees, that is, must contain within it, more than the mere pictorial content. Something of the history of the picture must infuse the experience. How so?

A nightingale sings?

In 1790, Immanuel Kant considers our response to the song of a nightingale, a thing of natural beauty.

What do poets praise more highly than the nightingale’s enchantingly beautiful song in a secluded thicket on a quiet summer evening by the soft light of the moon? And yet we have cases where some jovial innkeeper, unable to find such a songster, played a trick – received with greatest satisfaction [initially] – on the guests staying at his inn to enjoy the country air, by hiding in a bush some roguish youngster who (with a reed or rush in his mouth) knew how to copy that song in a way very similar to nature’s. But as soon as one realizes that it was all deception, no one will long endure listening to this song that before he had considered so charming (…) (Kant 1790, Ak. 302)

Although Kant is proclaiming the supremacy of nature as a ‘free’ beauty, it is a clear example of how we can be cheated by our perceptions; and in so being cheated we lose all interest in that which we had previously found beautiful.

To the drawings themselves

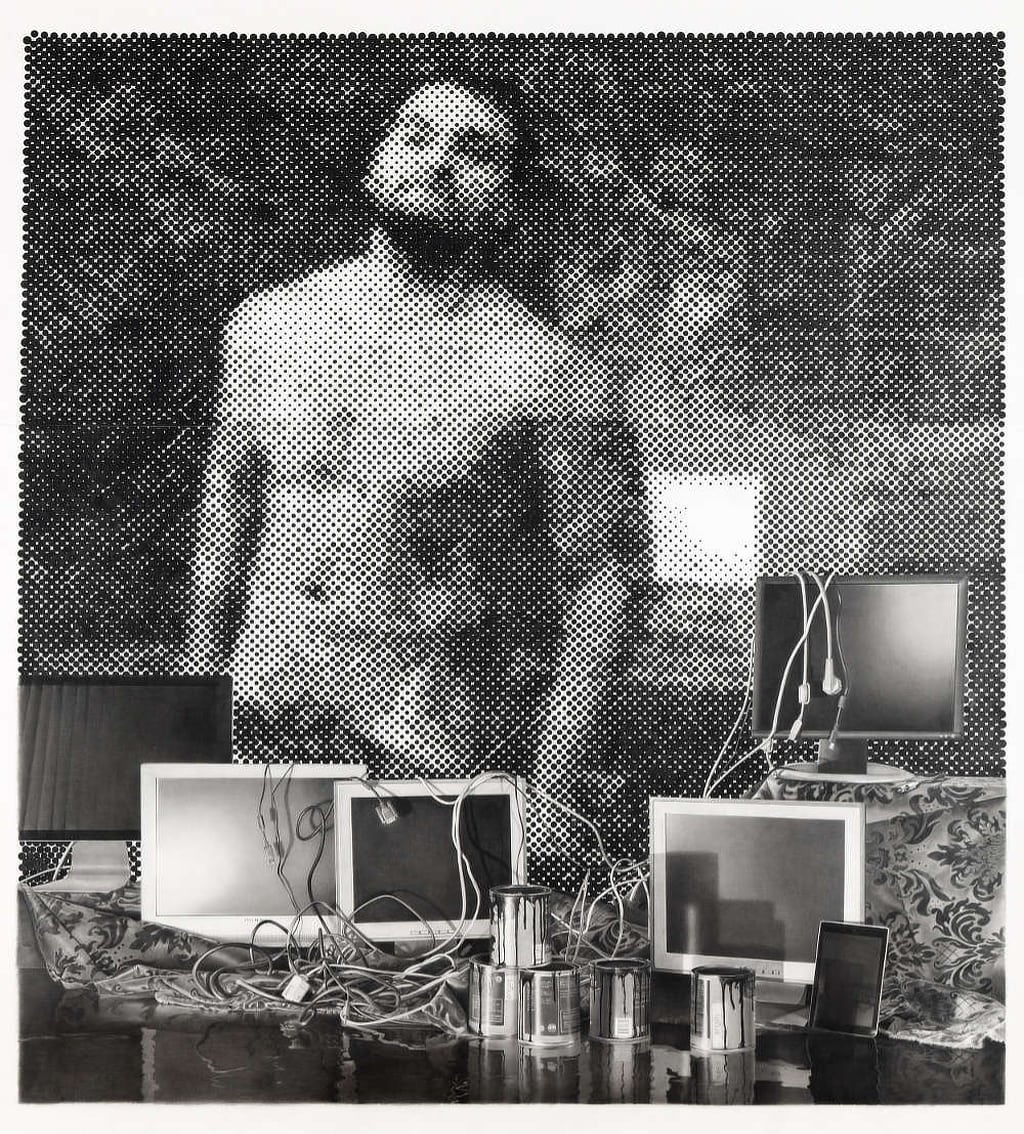

David Haines, in Your Fluffer, 2017, uses a drawn half-tone image that reverses this, whilst exploiting the very hierarchy. Half-tone was introduced to black and white photography so as to concentrate dots of varying diameter so that different densities of black ink would be spread across a newspaper page. Thus, giving the effect of tone. It enabled an image with ‘quasi-tonal’ properties to be printed only in black ink. Each of Haines’ half-tone dots is hand drawn.

David Haines, Your Fluffer, 2017. Pencil on paper (framed), 205 x 184 cm.

The Computer screens, their connecting wires, the i-book, the paint tins and the arabesque fabric are all drawn in hyper-realism. This gives a neat twist to the picture. The living man, the fluffer (or is he the fluffed?), is drawn as a picture of an image, whereas the screens and their supporting cables, the paint tins and the tapestry are all images (or the means of establishing images) that are drawn hyper-realistically. The screens show nothing – a negation of images where you might most expect to find them. One of the earliest forms of media depiction – the half-tone – takes us into the human presence. He is the fluffer. (A fluffer, in the sex-film industry, is someone who use feathers or whatever he can to stimulate the performer before he goes into action.) Perhaps, if not too attenuated, he prepares a sort of reality to be reproduced as pornographic image. And some have thought that all imagery is, in some sense, pornographic.

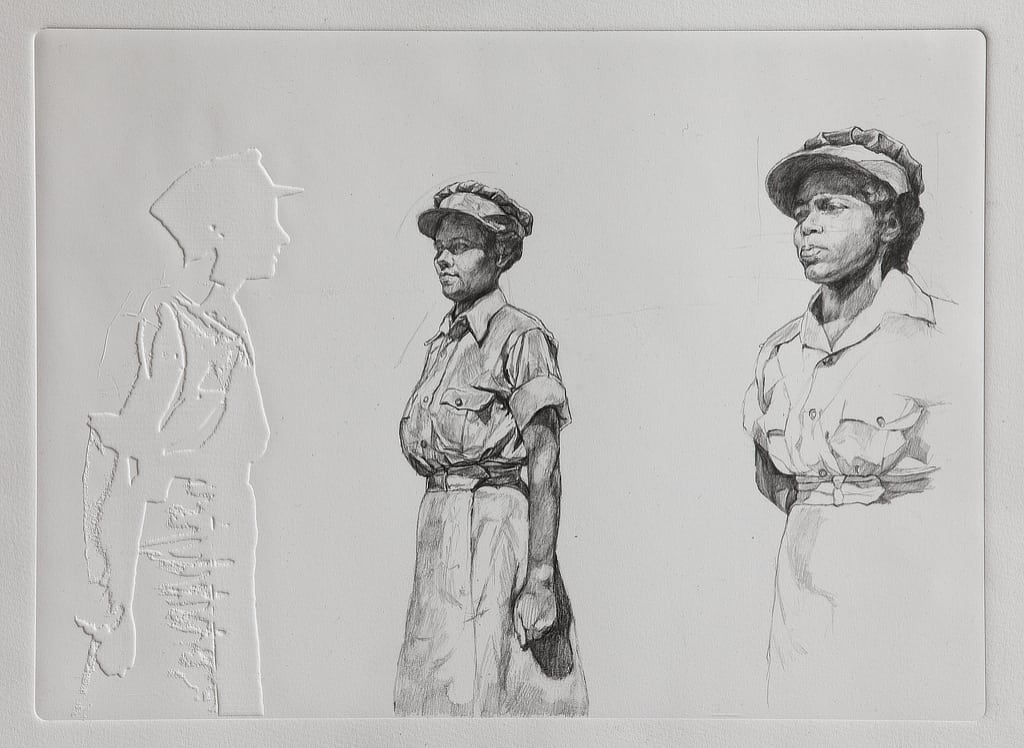

An image in the Oxford installation of this show is Barbara Walker’s Parade III, 2017. Two black servicewomen from the second world war are on parade. These are intensively drawn images that show their subjects bereft of background context, floating, isolated on the drawn sheet. To their left is their commanding officer seen barely present as an embossed shape on the paper – white.

Barbara Walker, Parade III, 2017, Graphite on embossed paper, 51 x 61 cm.

In Walker’s pictures there is something of the sensitivity of the monk at his desk carefully spending the time allotted to him illuminating manuscripts. The feeling is of atonement for the hardships of these women who stare ahead of themselves proud and strong.

On a video playing inside the gallery there was one of her works that showed graphite drawings of black servicemen wearing fezzes. With no information at hand, I imagined them to be recruits to Franco’s African Regiment, the moors who came across to fight for the nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. Not their war. But these men were rendered in their stoic beauty, lined up for inspection.

Art and craft; and the line between

Gill, being profoundly dyslexic, was a great dictator. It is unlikely he would have read Kant at The Slade. (It was not on the reading lists.) But his clever asides on art education as he witnessed, is testimony to how far we might go back to consider these matters. Kant tells us,

Art, is likewise distinguished from craft (…) It is advisable, to remind ourselves that in all the [fine] arts there is yet a need for something in the order of a constraint, or, as it is called, a mechanism. (In poetry, for example, it is correctness and richness of language, as well as prosody and meter.) Without this the spirit, which in art must be free and which alone animates the work, would have no body at all and would evaporate completely. (Kant, 1987, Ak. 304)

And later Kant warns,

Even though mechanical [craft] and fine art are very different from each other, since the first is based merely on diligence and learning but the second on genius, yet there is no fine art that does not have as its essential condition something mechanical [skilful], which can be encompassed by rules and complied with, and hence has an element of academic correctness (…) Now since originality of talent is one essential component (though not the only one) of the character of genius, shallow minds believe that the best way to show that they are geniuses in first bloom is by renouncing all rules of academic constraint, believing they will cut a better figure on the back of an ill-tempered than of a training horse. Genius can only provide rich material for products of fine art; processing this material and giving it form requires a talent that is academically trained, so that it can be used in a way that can stand the test of the power of judgement. (Kant 1987, Ak. 310)

It is odd that the schisms and squabbles, that have pre-occupied artists and theorists since Greeneberg’s mis-reading of Kant – as a basis for his adherence to formalist abstraction – should be traced back to so eminent a philosopher. The work on show at Drawing Room and at Modern Art Oxford, is testimony to the deep-seated worries that artists and theorists have concerning the making, and the nature, of fine art in general, and of drawing in particular.

References:

Gill, A. A., (2016) Pour Me, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Kant , I., (1987) Critique of Judgment, Indianapolis: Hackett

Straine, S., (2018) ‘Nomadic Drawing,’ in A Slice Through the World: Contemporary Artists’ Drawings, Exhibition Catalogue, Drawing Room and Modern Art Oxford.

Winters, E., (2018) ‘John Stezaker’s Photo-Collages,’ in Trebuchet, Issue 4, The Body.

Illustrations:

Barbara Walker, Parade III, 2017, Graphite on embossed paper, 51 x 61 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Chris Keenan.

David Haines, Your Fluffer, 2017. Pencil on paper (framed), 205 x 184 cm, Courtesy the artist and Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam

Exhibition:

A Slice Through the World: Contemporary Artists’ Drawings, is at, Drawing Room and Modern Art Oxford.

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.