I

From New York to Captiva, Florida

Spreads, is the title Rauschenberg gave to this series of work that occupied him from 1975 through 1983. In the catalogue essay, ‘Roots Spreads,’ Elisa Schaar tells us that the sequence of work is occasioned by the installation of his mid-career retrospective show that toured America during 1976 (Schaar 2018). The preparation for that exhibition gave Rauschenberg the opportunity to look at his work to date and take stock.

It also coincided with the move from New York City to Captiva, Florida; signalling a lightening of mood, compared with the still thriving existentialist cry of the expressionists in New York. Captiva, to where he moved in 1970, was an opportunity for rejuvenation.

Rauschenberg is an American artist – Americana, his material. This needs some context. European artists, from the early twentieth century, had looked to transform the way that art was made and, thus, perceived. Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Francis Picabia had begun to include ‘everyday’ signs and images in their paintings.

Collage in European Modernism

Artists collaged, assembled or otherwise constructed works out of everyday flim-flam. Arte Povera, Dada, Surrealism, Constructivism, and Conceptualism all proceeded by agglomerating found objects and images, recombining them into new works. In the process of assemblage, they stripped these objects of their everyday function, thus revealing their (bracketed out) phenomenological aspect.

These conscripted objects offer up their visual interest in and of itself. In 1912, Picasso incorporated oilcloth printed with the pattern of chair seating into his cubist painting, Still Life with Chair Caning. Kurt Schwitters made compositions out of bits of detritus, sometimes painted, sometimes not. The American ‘outsider’, Joseph Cornell, fashioned assemblages in small boxes from materials bought in penny arcades or from second hand book stores or flea markets. No longer representations, the everyday objects were recruited to the status of material. So, under this conception, ‘everydayness’ was promoted from aesthetic theme to aesthetic object – the compositions might call for aesthetic control, but with freely available tickets, posters, bottle and packet labels, newspaper and magazine images, bobbins, glass marbles, test tubes, corks, and watch springs, the aesthetic of the everyday object now played its own part in the construction of images. The line between the visual fine arts and the everyday visual world became porous – permeable.

The Internal Frame

Apollinaire would call “an internal frame,” … the projection of the outside into the inside of the work so that art and reality would change places and the observer would not know where one began and the other left off. This was the principle Apollinaire saw in collage, with its structural condition of mise-en-abyme: a hall of mirrors in which the real – the bit of newspaper – becomes the “ground” for a “figure” that in turn becomes a figure of the “ground.” (Krauss 1998)

Christopher Green, expanding the notion of the internal frame, writes of the moment Apollinaire identified two innovations recruited by the cubists to the art of painting:

In the section [Apollinaire] devoted to Francis Picabia (b. 1879) he tackled Picabia’s habit of writing his titles on his paintings. They must, he said, ‘play the role of an internal frame, as do authentic objects and precisely copied inscriptions in the pictures of Picasso’. In that moment in March 1913, the poet-critic pinpointed two factors newly introduced into painting which were to have devastating effects: the object and the word. (Green 2000)

The use of text and found objects act as internal frames in two ways. In the first case, they appear to us as flat and, therefore, part of the flatness of the painting to which they contribute. In this they limit the depth to be seen in the painted surface. In the second case they act as an internal limit upon that which is depicted. So that their appearance inside the picture pulls attention back to the relation with the external frame. The internal frame, in other words, acts as a surface around which depiction operates.

II

Art and Everyday Experience

The philosopher, Arthur Danto, himself a painter, would be encouraged to bring philosophy to bear upon modernist art. In his paper, ‘Artworks and real things,’ Danto focuses attention on the line to be drawn between the world and those parts of it, somehow quarantined off into a separate realm: art (Danto 1973). Art, according to the ancients, provides us with the world in imitation. As such, Danto suggests, art has been thought ontologically inferior; a mere copy of the real thing; a dilution of reality.

Danto locates the original diagnosis in Plato’s famous attack on artists in The Republic (Plato 1928). ‘Bedness’ is an ideal bed, the one and only bed, toward which beds-in-the-world approximate. Each instantiated bed in the world is a shadow of that ideal bed. An artist’s representation of a bed is a shadow of a shadow of the ideal bed. And so, ‘artists have sought a way towards ontological promotion, which means of course collapsing the space between reality and art.’ (Danto 1973, 2)

Rauschenberg to the Rescue

If mimesis is the correct theory then we are led to a dilemma: ‘Art fails if it is indiscernible from reality, and it equally if oppositely fails if it is not.’ (Danto 1973, 4) The way forward ‘is to make non-imitations which are radically distinct from all heretofore existing things. Like Rauschenberg’s stuffed goat garlanded with a tire. It is with such unentrenched objects, like combines… that the abysses between life and art are to be filled!’ (Danto 1973, 4-5) Rauschenberg’s combines belong to this conception of the everyday in art.

“Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two,)” – Rauschenberg

In an essay on Rauschenberg, Rosalind Krauss describes his work as “a form of collage that was largely reinvented, such that in Rauschenberg’s hands the meaning and function of the collage elements bore little relation to their early use in the work of Schwitters or the cubists.” (Krauss 1974)

If Rauschenberg and his contemporaries sought ‘ontological promotion’, Minimalism goes in the other direction – and achieves ontological relegation. Artworks become mere objects – for there is nothing but painted surface. The flat painting really is an object – its ‘objecthood’ comes to the fore. The ‘painting’ just is a three-dimensional object amongst others. There is no longer a kind of ‘seeing’ that might be called upon in order to ‘get into’ the picture.

III

The Reinvention of Collage in America

In Spreads, Rauschenberg has developed the collage of European Modernism and used it as a way of both heeding and deflecting the American Modernism of Clement Greenberg. Greenberg had insisted on the abstract formal properties of the painting as its aesthetic basis. Representation was not held to be a formal property and so, it is no longer to be considered as a necessary feature of painting. Indeed, given the contingent nature of representation, it might be thought an encumbrance to our connection with the aesthetic. Greenberg thinks that it is because the old masters have aesthetic formal properties that they are great works of art. Their representational properties are simply irrelevant to their aesthetic worth. The flat objecthood of the painting, with its colour arrangement, is all that counts.

Art’s Practice and Appreciation

For each art, I take it, there is to be some characterization of what constitutes its practice, and, by extension, what constitutes its appreciation. Concerned with the art of poetry, T. S. Eliot writes of the constraint upon modernity exerted by tradition. Each artist must fit herself into the history of her particular art. In so doing, she adjusts that history, renewing it, refreshing it and readjusting it. Through this process, her work is thereby situated.

In painting, by analogy, the spectator’s willed experience includes attention to features of the paint surface in her achieving her aesthetic experience. Those features would be excluded from, masked out of, her experience, were she to direct it toward another pictorial ambition. It is here that we recognise Eliot’s claim that the artist, in providing a work for her audience, situates that work within the tradition in such a way that the spectator can appreciate her intention. The viewer’s imaginative experience of the work places it within or against other works and thereby sees it as striking up an attitude to those other works, so to speak. It is as if each work gestures toward other works and that recognising these gestures affords one dimension along which meaning in the arts can be developed and appreciated. Eliot offers resources for an account of the importance of assumption and expectation in our appreciation of works of art within a specified medium.

IV

The Achievement of Spreads

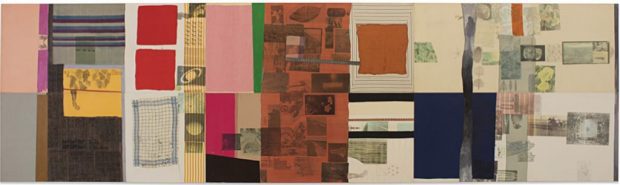

This body of work provides scope for regarding the paintings as flat whilst inviting the spectator into the pictorial world collaged. The title suggests the flatness of the designer’s table upon which photographs are littered, perhaps we might think of the page designer’s studio in some busy press office or in some upmarket fashion magazine.

Robert Rauschenberg, Half a Grandstand (Spread), (1978)

Half a Grandstand (Spread), (1978), has an aluminium ruler that follows the line of a slightly angled (from the vertical and horizontal) rectangular picture. The ruler is seen to be ready to make a cut, rather than to measure the the picture; and so the whole of the work looks like that of the studio work table. As if we are looking down and about to perform an operation – slicing into the edge of the picture. This has the effect of flattening the image. We see it as a paper print lying on the flat cutting table: a thing.

Robert Rauschenberg, Shroud, (1979)

Rauschenberg’s use of text and repetition of images adds to this disruption of the depicted scenes in his paintings. Text is something that is looked at; and not looked into. The uses of text serve to place the pictures on level ground with the pictures; so that looking at the texts encourages us to look at the pictures in the same way.

The repetition of images, often juxtaposed, serves also to flatten each instance. It does this by reminding us that the image is only an image and (pace Plato and the ancients) not a mimetic reproduction of the scene depicted.

The technique, however, of silk-screening and of solvent transfer further conspire to flatten the image, so that the picture looks like a photograph first and foremost. It is only after we have accessed the photograph as graphic component that we see in it the Americana content. Then the juxtapositions begin to take on a poetic, associative dimension.

This contrasts with the cubists’ and Schwitters’ European collage. The cubists used bits of found stuff and text to contribute to a single image project, albeit a fragmented picture, it was still a single image assembled from multiple points of view. Schwitters used found material to build abstract compositions. Rauschenberg builds diverse images and so breaks up the entirety of the whole composition into discreet pictures, each of which, as a flat coloured object, contributes to the wider composition.

In this, Rauschenberg’s refusal to let go of pictorial content puts him at odds with Greenberg’s modernism. However, his refusal to collage coherent composite pictures and his refusal to discount entirely the pictorial content provides a way of correcting Greenberg in a way that blocks the relegation of the painting to mere object – in the way that Minimalism demanded.

Robert Rauschenberg Spreads 1975-83 is at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, November 28, 2018 – January 26, 2019

References:

Danto, A C. (1973) “Artworks and real things,” in Theoria, pp. 1-17.

Eliot, T S. (1975) “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” (ed.) Frank Kermode, London: Faber & Faber

Green, C. (2000) Art in France1900-1940, Yale University Press, p. 128.

Krauss, R E. (1974) “Rauschenberg and the Materialized Image,” pp. 36-43.

Krauss, R E. (1998) “Dime Novels,” in her The Picasso Papers, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 218.

Plato (1928) The Republic, Book X, (Trans.) B. Jowett, Oxford University Press.

Schaar, E. (2018) “Roots Spreads,” in Exhibition Catalogue, Robert Rauschenberg, Spreads 1975-83, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.