On first being led into Soho’s notorious Colony Room Club, the guest of a habituated member asked in dismay ‘What’s that smell?’ Without looking up, another member, stooped in a corner, muttered, ‘Failure’. The old salt stared into his wine – just a sailor fathoming his mermaid. ‘Failure,’ he mumbled again more faintly, this time not joking but sinking.

***

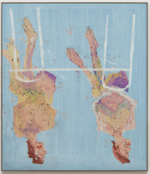

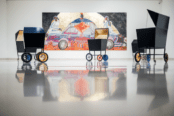

Darren Coffield, artist, author and former member of the Colony Room Club, has re-created in significant detail the seedy first-floor bar. The once much-loved (but now sadly shut down) members’ club in bohemian Soho opened its doors in 1948, when lesbian mondaine Muriel Belcher paid the then unknown Francis Bacon £10 a week to fetch ‘interesting’ drinkers into its embrace. It was a speakeasy frequented by homosexuals, artists, prostitutes, writers, politicians and petty criminals. Its latest incarnation is as a work of installation art, occupying a basement just off Regents Street. How best might we think about such work?

I

More than two hundred years separate two important books on the philosophy of art. Peculiarly, the most recent, Dominic Lopes’ Beyond Art (Lopes 2014) makes fresh the illumination we might find in Immanuel Kant’s eighteenth-century Critique of Judgement (Kant 1987).

Beyond Art has two novel (and controversial) arguments. One, is that any work of art, in order to be a work of art, has to belong to an art-kind. That is to say, there are no ‘free riders’. There is no intellectual space for works of art that do not belong to art-kinds. Thus, the question ‘Is it art’ has to be passed on to the individual art kinds. It becomes: Is it painting? Or: Is it sculpture? Or: Is it music? Et cetera.

The book, at least in part, is motivated by Lopes’ ambition to underwrite conceptual art in a way that systematically places that body of work within the critical discourses of the history of the fine arts. The early twentieth century avant-garde had determined the default position that anything can be a work of art. Duchamp notoriously stated, ‘If I call it art, it’s art’ Lopes challenges that position. At the same time, he confers fine-art status on works that had attempted to defy classification. He licences, for instance, Robert Barry’s Inert Gas Series (1969), regarding it as a work within the art-kind he calls conceptualism. To do this, he has to provide a medium-specific profile for conceptual art and, thereby, make room for it as a legitimate art-kind. That is another matter, but it serves as a model for how we might cast light upon Installation Art.

Beyond Art’s second argument is that, in providing a medium profile for an art-kind, we delineate what lies inside the specification and what lies beyond. The medium profile must contain within it the network of connections between works that together constrain the art-kind as a coherent whole. This is not to say that a painting is made of paint; and it is certainly not to say that if anything is made of paint, it is a painting. Lopes exemplifies the problem as ‘the coffee mug objection’. If a piece of ceramic art by Grayson Perry is to be admitted, then why is not my coffee mug – since both are made from ceramic slip? (It has been claimed that Clement Greenberg unwittingly gave minimalism warrant by permitting such a weak conception of a medium. Thus, minimalism attacked abstract expressionism from within, whilst conceptualism attacked it from beyond .)

A feature of Lopes’ point of view is that there is nothing that binds each of the art-kinds to all the others. In the eighteenth century, for instance, Abbé Charles Batteaux had sought to explain the unity of the fine arts by claiming that each exhibited mimesis: what legitimises each art-kind’s inclusion as a fine art is that it in some way copies beautiful nature. Lopes’ rejection is of such a unitary explanation.

An art-kind’s medium profile must internalise its history and, thereby, its suitability to pursue aesthetic ideas. In the case of painting, for instance (pace Greenberg), the case is made that painting pursues its aesthetic ideas in the fabrication of representational content. That said, if we are to consider Installation Art as an art-kind, we must address its medium profile.

II

Kant, writing at the time of the systematisation of the fine arts, argued for a distinction to be made between the mechanical and the aesthetic arts. The mechanical arts are those which require a degree of technical skill and which give rise to art products that we might nowadays regard as crafts. The aesthetic arts are then subdivided between the agreeable and the fine arts. The former are thought to be those pastimes we enjoy but do not require intellectual reflection. These include witty and jovial conversation over dinner; furniture music, as conceived and composed by Erik Satie, over which dinner guests might talk; card games; parlour games, including billiards and anything designed for enjoyment, but which are not made to last. Nor are the agreeable arts undertaken with any serious reflection. We might add to this list, for instance, football and reality television.

The fine arts Kant regards as having individual natures, some of which might have overlapping features. For instance, painting, sculpture and architecture might each employ drawing as a constituent practice within their overall medium profiles. What the fine arts have in common, but which does not unite them, is their suitability to convey aesthetic ideas. Such ideas have a technical meaning in Kant’s aesthetics… (read the article in full on Trebuchet 15)

Read more in

Trebuchet 15: Installation

Featuring:

Installations as theatre

Giuseppe Penone

Michael Landy

Annette Messager

Karolina Halatek

Sounds Art as Installation

Jean Boghossian

Jon Kipps

Chantal Meza

Photos by Peter Clark © Peter Clark

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.