Despite valiant efforts to rebuild and repurpose, the city of Hamburg is still visibly scarred by the high tonnage impact of WWII ordnance. Gaps open abruptly in the city’s mid-rise urban squeeze. They’ve been artfully converted to pleasantly wooded public gardens, dog parks, meandering walkways and hillside viewing points, but there is no mistaking the channels of bombing runs carved through the city from its warehouse district up the steep banks of the river Elbe.

Defiantly countercultural and threadbare in parts (Sankt Pauli), comfortably bourgeois in others (Othmarschen), Germany’s second-largest city has strong bones; the Elbe’s south bank spreads to the horizon with shipping containers, wind turbines, serried loading cranes and the constant glide of behemoth freight ships. A stinging riposte to the deprivations of the 1950s, the almighty scale of Hamburg’s mercantile dominance is a showcase of post-reunification Germany’s economic flex.

The Altonaer Balkon, a tract of leafy parkland overlooking the ordered industrial energy of Hamburg’s port area, is almost aggressively European; cyclepaths, recycling bins, pre-schoolers nestled in the loading bay of cargo bikes, alfresco kiosks serving rosé in stemmed glasses (with a one-euro deposit). Here, in June, it’s a panoply of greens, from lush grass to midsummer oakleaf.

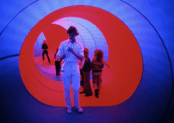

Emerging from the greenery, LUAP’s Pink Bear looms assertively vibrant in tones of bubblegum, magenta and plum. Scaled up from a six-centimetre plasticine model—itself a re-imagining of the bear suit the artist wears in his photography/painting works—what is on show at the Altonaer Balkon is, in effect, a detail. Assembled from 3-D printed panels around a sparred plywood substructure, the four-metre-tall head is disembodied, protruding from the soft Hamburg grass as if buried to the neck. As evening sun sidelights the jumbo-corduroy grooves of the extrusion process, glittering highlights of gold outline depressions in the surface. Fist-sized shadows deepen to bruises of violet.

“I don’t need it now,” Paul Robinson says, watching as visitors tentatively touch, explore, and ultimately enter the not-quite-toylike structure. He means it in a therapeutic sense, rather than professional. The bear has two points of significance to Robinson. One, in that it’s the defining, recurring avatar of his current artistic output, but secondly, it’s the lifeline that pulled him out of a self-destructive psychological spiral that threatened to destroy him.

Long story short, the idea came as a result of a series of cognitive behaviour therapy sessions. Asked to pick a mental image to conjure up times of past happiness, Robinson fixed upon a pink bear from a photograph of himself as a child.

From there, the tale grew in the telling. Working under the artistic name LUAP, Robinson took the motif and ran with it. First came the bear suit; a lifesize costume in which to meet the world head-on. “I had an inability to connect with people. The bear suit helped with that”, he explains. LUAP’s early practice involved travelling to extreme points of the planet (Mongolia, Patagonia), capturing photographs of the shocking pink bear in situ, from which reference shots Robinson painted photo-realistic (or, to be more accurate, reality-enhanced) canvases.

Collaborations with Christie’s, Nikon, a sponsorship deal from Mariott International, and now an associated €250,000 award fund established with the University of Europe for Applied Sciences…suffice to say that the pink bear’s soft power polemic has hit upon a formula that captures the attention of institutional art patrons.

Is it simply a corporate logo? A universally unobjectionable mascot created by a brand-savvy fine artist with a background in corporate design? It’s tempting to write it off as just that, and to feel smug and sophisticated for having identified it as such. Closer examination, though, reveals otherwise. In the context of public art animals, Pink Bear’s vulnerable expression owes more to the plaintive slump of Urs Fischer’s ‘Lamp/Bear’ than to, say, the witless populism of Jeff Koons’s “Puppy”. The bear itself is too ambiguous, its features too nuanced, to be easily dismissed. Where is the expected smile? Why does its eyes convey hurt? Is there also a hint of hope there?

Nuances like these are red kryptonite to corporate branding. “If it had a smile, it would be cheesy,” Robinson confirms. Instead, Pink Bear’s ambiguous features prompt a reflex for concern rather than the dopamine soothe of a cutesy cartoon sprite. “I’m not,” he emphasizes, “trying to make a Disney character.”

In fact, the artist’s intent was to replicate the Pink Bear costume, not the character. Hence the woven effect of the eyes, the texture of the nose, the divots of the surface to suggest plush fur. The technical challenge of convincingly transposing those details to a four-metre public installation involves laser scanning, 3-D printing, interior frame carpentry, freight transport, and panel-by-panel assembly onsite, but it is in the precision of the process that the artwork transcends the more usual molded glass-fibre approach to such projects.

The costume, then, is where the significance lies. For Robinson, it was a second skin that overcame his disassociative inability to connect with others. Pink Bear was the vehicle that pulled him from the downward spiral that his life had become. From that early idea as a mental image of happiness, the costume became an enabling tool—a superhero outfit to enhance abilities.

“The bear pushes you to go further than you could. Like, I was frightened of horses, but [wearing the suit on horseback in Mongolia] let me confront that. It’s not about hiding, it’s about standing out and pushing further. It’s not a mask to hide behind.”

And while the intricacies of scaling Pink Bear up to installation size are certainly of technical interest, the artistic challenge is in taking that personal connection to a larger audience. “When I started Pink Bear, I didn’t imagine having a giant bear head in Hamburg,” he admits. “For me, the bear is more of a vehicle now. A figure that I use to navigate current thoughts. The suit was a safe space for me. This is a bigger safe space for other people.”

Robinson’s intent for the piece comes through when he speaks of it. The Grimsby man’s description of process, biography, and intent are direct, lacking the deliberately quotable soundbites of a media-primped self-marketer. His commentary is underpinned with a survivor’s wry stoicism. While Pink Bear will almost certainly become a bigger project as it gains exposure in the higher echelons of the art world, there is substance beneath the polished veneer.

“It’s for everyone, not just kids. Watching people interact with it, people of all ages are delighted by seeing it. Everyone rubs the nose! But lots of them have been asking me what it is, what it’s about.”

For Robinson, it’s simple “It’s about healing, about overcoming. If it gets people even talking about mental health, it might help other people address their own. The bit I really love is the painting, but bigger projects, galas, more exposure… it hits more people.”

Unexpected, but not entirely incongruous against the post-industrial backdrop of Hamburg’s cranes and containers, the benign curves of LUAP’s signature motif gather the curious and the charmed. They take fewer selfies than you’d expect—it’s still an artwork rather than an Insta prop—but smile more often.

Take the win, LUAP.

LUAP’s Pink Bear is currently on show at the University of Europe for Applied Science’s Berlin campus.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.