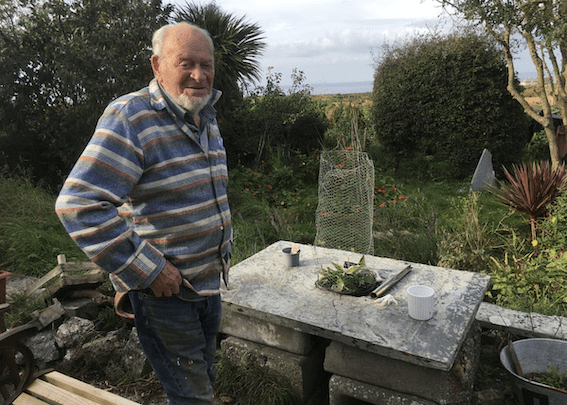

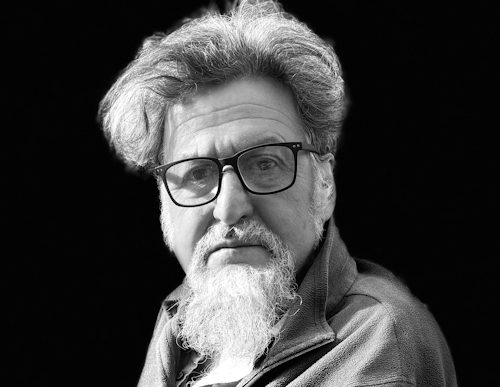

Part three of an extensive interview with performance artist and painter Ken Turner talking to former Action Space member and curator/writer Rob La Frenais, who joined the group in the early ’70s before going on to edit the ground-breaking Performance Magazine in the ’80s.

In part two of this interview, Turner reflected on the development of Action Space from its beginnings. In this, the final section, the artist ponders the influence the movement has had since its demise.

*****

I wanted to go into how Action Space connected to contemporary art institutions as opposed to galleries. And we have two examples. One is the Serpentine and the other is the ICA. And I think key to that engagement was Action Space and yours and Mary’s decision to actually collaborate with those institutions might have come from the individuals involved. Sue Grayson Ford for example, who is still active. I remember you launched an inflatable rocket at the Serpentine in Kensington. Gardens.

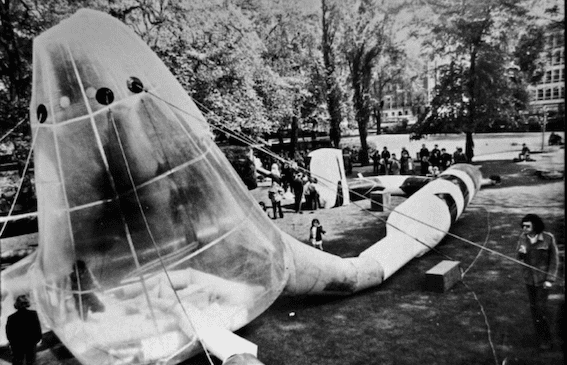

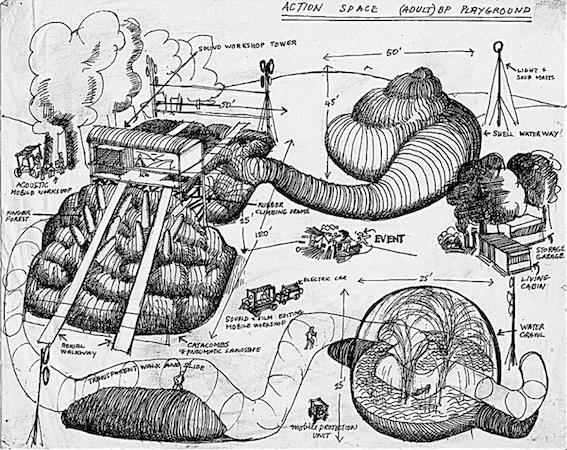

Yes, Royal parks. It was beautiful weather. Bank holiday, three days and setting up. Four or five days setting up because we had the scaffold inside the arena and as a photograph show with performances. It was the end. It was 1978, right at the end. That’s when I resigned. To the shock and horror of everybody. It was the culmination of my dream, actually. Not so much the philosophy, but it was all there. And the cooperation I had from everybody there, even though they knew I was ending it. They all collaborated and performed and made things. And a whole set of Arts Council guys were sitting in the gallery. In the gallery looking out to the garden. And then we as Action Space set the rocket and did a launch, and I climbed right at the top and looked out to the Serpentine itself, and they said, oh, it’s lovely. They really like the growth, the erection of this almost phallic rocket. But we did a performance of astronauts afterwards, and they said they didn’t like that. So that was performance art.

Well, there was actually quite a big prejudice in the Arts Council against performance art at one point. So let’s go on to the ICA now. I remember the friendly person there would have been Ted Little, the director at that time. And like all ICA directors, he had a lot of problems and ended up leaving. But it was as if he had invited Action Space in for a building takeover.

The Soft Room (at the ICA) was really quite amazing. Because Caroline was doing the introduction as people came in, and she had these sparkling eyes, boring into people. So we were performing as individuals as well as we did outside and inside that gallery. We took it over. The performance was people going in and the performance was the inflatable to themselves inside a blow up structure with lots of big spheres and big objects, things flying around. And I think Robert Stredder disrobed.

Yes Robert took his clothes off. He’s very much from the counterculture. Very different.

Well, he did, because it gave him the freedom to come in and do what he wanted to do. Just like that. And it was great. I mean, his bicycles and his circus things were amazing. He was a good raconteur.

So the nature of the engagement with the ICA — was it problematic? Was it easy? Was it difficult? I’m trying to remember — nothing’s easy.

It was more comfortable. And then we invited the kids from Wapping. Do you remember that? They broke the windows and stole from the café, but the ICA took it on the chin. They didn’t complain, they just said, ok, that’s what it is. So the kids from Wapping were amazing. They loved us, we were their heroes. And they said, oh, we’ve come up to London, we’re going in the ICA and we’re going to Trafalgar Square and do some pickpocketing.

This is something I remember about working on the estates. They were so separated, those council estates, even though geographically they were about as central as you could possibly get in London. Even though it was close, it was like going into a different country.

Yes, it was like an invading. It was like an invasion group going in and getting spoils from people’s pockets. They said, they came back when we were in Wapping, they came back and said, look, sunglasses — worth a fortune!

Very funny. And also, I remember we marched up to Trafalgar Square and did something up there, didn’t we?

We did an event. We got permission from the council, because you can hire it or you can just say, I want to use it. And they say, okay, fix the date and you can use it. So we did. And we gave speeches from the plinths, from Nelson’s Column and had a microphone set up there and told the crowd about the arts and what was happening in the arts and that we were avant-garde and all that kind of stuff. And we did jousting in Trafalgar Square, which was amazing, the photographs of this crowd.

But that’s the thing, you see, it drew people in and, okay, we were at the same time spectacle and entertainment, but they didn’t know we were artists. That’s a sort of really interesting thing, because we had the confidence of being avant-garde artists, if you like, or going back to revolutionary days of the arts. And whether it was from Russia or Paris and Dada or Bauhaus, that was our link. We were linked up through centuries back to Russia.

At the ICA, during that conference that we organised and invited people we knew would object to our position, such as Ed Berman, for Interaction. We had a conference on art and the community. That was the moment when that battle, if you like, was formally declared, I felt, is that not right?

It was officially pronounced. This is a viable form of discipline in art as a community artist. But they downgraded it finally to ‘art workers’ .It was working for social benefit and not for artistic advancement. So they opened up a big rift between the artists who were performing firstly as revolutionaries or rebels, working outside the arts scene and going into streets and parks and whatever, schools. Don’t forget that we went to schools and we were carrying a banner which said, we are artists in a new realm, in the new territory of the outside, from the gallery system and the corruption that goes on there and all the argy bargy of money.

So, the Arts Council was showing their ignorance of not looking at the possibilities that we were setting up — not just Action Space, but Welfare State and even Ed Berman, if you like. But people like us were doing things which were spearheading some kind of real modern movement and development, relating back, as I said, to Russia, to Bauhaus, to all those things that had been going on. And it was also part of the ’60s spirit where we were anti-institution.

Now, of course, after Brexit, we see this excessive instrumentalisation.

What they were actually doing was putting a kind of knowledge around that artists could work in the community and they could work in the community to the benefit of the community and themselves and to the artists. That was the idea. But it failed with the artists because the artists were second-rate. All they were interested in was craft and design. It’s what Boris Groys said about design and art, he said that’s what happened in the Russian revolution. It became design rather than art.

I’m not sure if it comes down to artforms or genres.

It is! It’s not like design or ‘I design this object’, it’s design in the mind. It’s a philosophy of design. So the philosophy of design is very different to the philosophy of art. And that was where we separate. So the community artworker is a designer. He designed for the community using aesthetics. Because they want you to design things rather than artistically form things autonomously, intuitively. imaginatively. And be autonomous. Painter. I’m a painter. I’m autonomous. Nothing interferes with my work. Right?

It wasn’t about going in with a formula. Isn’t that right? It’s intuitive engagement.

Intuitive is a funny word. I mean, where does the intuitive come from? Where does the message come from? Where does your direction comes from? It comes from a deep feeling about an unease, about an established position, the establishment. And that unease propels you because you’re pushed out of it.

You would come up with a response that would maybe surprise and shock people, but you would intuit the correct thing to do. You knew the correct thing to do. That’s what you were trying to say. Is that not right?

Yes. Well, you had to. You had to rely on your own resources, and your resources were something deeply felt within you. Call it intuitive, you call it unconscious desires or whatever, but it’s like improvised dance. So when you’re doing improvised dance, you see the space before you go to it. And so that is how it works. It’s using your mind and the facilities of your brain to actually envision something real beyond yourself. Right. And beyond the situation that you find yourself in. So if you call that intuition, fine, that is the definition of intuition.

At the conference at the ICA, Ed Berman and others stood up and said, we can’t go on like this. Basically, he said, you can’t carry on doing what you’re doing. You anarchists, you don’t have a methodology that’s suited.

He was a sensationalist. He would say anything that caused a sensation, a vibrant sensation. But the conference was organised by Action Space. I let him speak! Because I should have got up and realised that he was going to take over, like a domineering spirit. He wasn’t an anarchist, he was a plutocrat. So he goes and gives a whole speech, stirring like a politician. Artists are not politicians. They don’t play with words like he did. It’s rubbish. Just rubbish. Rubbish, concerned with what real art forms are about.

Well, the main thing is he worked with actors, and they would go into these community situations with a script.

They had a script formula. Like a book of games. We made up our own games as we went along. And that going along with our own ideas of a game meant that people became involved in it quite naturally and organically. It was an organic sort of situation between people.

Well, that’s what I thought we were doing with the events in Action Space. We were trying to create other realities for a moment.

That was right. (laughter) I laugh when I think about it.Do you remember the time we sent the Bubble out in Stratford on Avon? The Bubble went out and Caroline went into the bubble and waved to the Queen as she passed in her launch. There probably were scuba divers underneath. But nobody was around to touch to stop us doing this! It was hilarious. I couldn’t stop laughing when I saw the Queen coming. Put the thing out! Come on, Caroline, get in there! It was amazing. And there were no police about, nobody stopping us doing anything. We could have launched a bloody submachine gun or something. Oh dear.

Can I ask you about what happened to Maurice Agis and what happened with the accident with the inflatable and the subsequent trial?

I should have gone to court and defended him. I was so horrified. And he died. It’s just tragic. He was such a good technician. He was doing a lot of commercial work as well. Building inflatable elephants. That was a great shock. I should have gone because he was a friend of mine, really. And I don’t know why. It’s because London is so far away.

I mean, you’re this age and you’re down here and I don’t think you can blame yourself for that but tell me what you would have said.

Well, I would have said, look, I’ve known him for several decades, and we kind of collaborated, but only in ideas. And I knew him and trusted him. And I also trusted him as a really absolutely fine engineer and technician and the way he built things. I think he built very complicated structures in inflatables by electronic means, not gluing. I would say he was one of the finest technicians of that discipline. And I would vouch for that. I would swear on it. He was one of the first to face the GLC with fire regulations and he invited the GLC into one of his inflatables. He quite dramatically got the Times newspaper, set it alight and put it into the side of the inflatable inside and it burnt a hole and the air rushing out, put the flame out. So I would have actually stated that because that was a detail of his competence, really.

The problem is, when you’re in the field with a lot of people, some of whom may be a bit rough, you do always have the issue of potential vandalism.

I think, as you remember, the reason why we did performances around the structure was to police it. The last thing I did was the Citadel. And when I did that, I had to manufacture it in a field just outside London that belonged to my accountant. Actually. It was a Scouts field. And he said, go there and do your work. So I did that. And then when I was in the field and I had a tent and I was cooking some sausages and a man in a suit approached me and gave me a letter and it was a summons to the court, the Bow Street court. The GLC has said — I learnt later — that they said that we have to take you to court because we believe that your structure is unsafe. And I said, okay, I’ll appear in court.

So I appeared in court at Bow Street, and I stood in the foyer for a moment or two, thinking, how should I face the judge and everything? I didn’t have a solicitor. I thought, well, I can argue this case on my own. I can say how I deal with the safety regulations and so on. And then a couple of guys came up to me from the GLC and said, can we come to an agreement? Because they didn’t want to go into court.

They settled out of court?

Yes. I said, well, what is the agreement? What are you suggesting? And they said, would you say and stipulate that you would only let professional people into your environmental structure? I said, yes, of course I would. That was the end of my contact with the GLC. When I put the structure up, I put a big notice up and said, only professionals allowed in here and they include unemployed and so on! A whole list of professionals. (laughter) And they didn’t get at me. They let it go. I mean, I knew immediately. They said, only professionals. I said, yes, sure, that’s great. Yeah, I’d do that.

A big occasion I can also recall was when Joan Littlewood was setting up a program in Victoria Park in London against the Vietnam War, and she asked me to join in her football match, Americans versus Vietnam. I said, yes, I’ll join in, but only momentarily, because I’m setting up an inflatable. And that was interesting because we set up just a square, big, square house, just the red one. And I got ballet dancers from the London school of Ballet to come, youngsters. And they went circling around this inflatable object. And I had a white rope, a nylon rope around, held by the public, held to keep everybody out of the arena, as it were. And then very gradually, this rope came in, into the inflatable.

I had flares, the old flares, orange flares in my pocket. And some of the boys larking about, pinched them from my back pocket and lit them. So we had orange flares. And then the boys, about ten of them, closed in into the inflatables. And so you had then a performance of those boys. With the dancers and the audience a little back from it. Giving them space to be involved in that way, whether they wanted to do it or not. I was saying to them, I was talking to them like mad. Yes, okay, that’s very good. I want you to enjoy this and join in with the dances. And they actually tried to do that instead of puncturing it or having a running battle. And then I gradually let the inflatable down. And as it went down, they all piled on top of it. And it was just a happy occasion, finally. But the police actually said afterwards, we could see that you were handling that incident very well. So we didn’t interfere. But they were there because we had told them we were there.

One of the things I remember very well was that we used these psychodramas in order to diffuse situations.

Psychodramas?

Well, I call them psychodramas that were dramatised in a certain way that also involved their own problems where they were. And those problems kind of got redirected through this anarchic focus in a sense.

I mean, their problems were alleviated because it was about spectacle and it was also about drama and theatre. It was kind of an open theatre, environmental theatre, if you like. As I was an environmental artist as I call myself, not a community artist. That was powerful enough to subdue or to change the direction of thought, feelings. It was about feelings saying, oh, what’s that figure doing? What’s that figure? And doing this. And then they would talk to the figures. That was then involvement within the drama of the whole environment.

Exactly what I’m saying. And one had to also use, like you did with those boys, strategies in order to distract people.

Well, the strategies on the spot. Sometimes you had to be intuitive, you had to be wide awake, and you had to sort of rely on your own courage, actually, and be fearless, you see? And that was exciting. That was exciting for me because I thought, well, I could deal with this. And in a flash of a moment, you could do this or that or anything to stop something awful happening. Although at the same time, we’d always say to the police where we are and what we’re doing. And in Sloane Square, for example, we could see them parading police dogs on the edge of the Square and they weren’t going to interfere until something happened — and nothing happened.

I’m thinking of more situations where we were perceived as posh or outsiders or something like that, where we really had to fight hard to actually get accepted.

Can you remember anything like that?

Yes a lot. Quite a lot. I can remember being beaten up (in Liverpool).

I was faced with knives, but then miraculously, nothing happened, in Wapping. I was challenged because not on the field or what we were doing outdoors, but inside the youth club. I took four women, including Mary, into the youth club, there was Marion and Catherine and two other people, I can’t remember, there was a youth club and the Wapping youth club had invited people across the river to come and join in. They had bands or celebrations of some kind. And then during that evening, and there were sort of low lights and music and everything, and I looked around and said, where are these ladies I brought in? They’re not here. So I went into a corridor and they were all kissing, being kissed by members of the invited group. And so I tapped everybody on the shoulder and said, come on, Action Space, we are now leaving. And so they disengaged themselves and I went into the open and the leader of that group — I described it like a Western in the book — and the young West Indian or whatever sort of leader of the invited group stood in front of me and challenged me to a fight!

The whole gang of people, audience as it were, retreated and left us two facing each other like that. And he said, I’ll only fight you alone, nobody will interfere, which is quite wrong. That was just a lie. And then I thought, how do I deal with this? I’ve done some jujitsu, how can I deal with this? And just at that moment, I wasn’t frightened. I just thought I was amazed, my amazement at what the ladies had done, being acquiesced to being taken off. And I just was annoyed at that. And I was just thinking, what could I do now? And I thought, well, I could use some of my techniques, which I haven’t really practiced, but will it be a fair fight? And I thought, no, it won’t be. And then just that moment, the locals, big boys of 17, 18 years old, crowded around me and crowded around the guests. And he took me out and the guy, the guest guy, said it would only be me he would be fighting!

Amazing. So what were the women doing? Were they using some sort of distraction technique? Why were they kissing? What were they doing? Maybe this was an early feminist kind of action. I think when we went into an event, this is my memory, we bundled into the back of the vans and the ambulances, no seatbelts and all that. We’d drive in and on. And in a funny way, it was a little like berserking or going into battle. You had to build up a sense of anticipation.

It was. We knew that if we saw tall tower blocks and little areas of scrubbed glass, we knew that it would be tough.And all the time I was thinking to myself, bloody hell, is this what an artist should be doing? Yes, we should, because there’s a motive behind this. It’s probably idealistic, but it is something that drives us on. And the excitement of the encounter, also.

There was also this issue that I feel that this public, the council housing, the way it was designed, was to almost re-emphasise the drabness of these people’s lives.

The criticism was that we would only be there for an afternoon. But in Wapping, we were there for a week. And that worked. Because the mothers, the families, understood what we were doing. The bigger boys understood what we were doing, and the men, the fathers, understood what we were doing because we knew that they had a pub just outside Wapping. And we scraped one of their cars and we dashed away hoping they wouldn’t know. But they followed us. And they said, we know you’re doing good work, but just pay for the damage and we’ll call it quits. I said, okay, there was a bond. You could build up that kind of bond and trust and that was the reason why I was escorted out of the youth club. Otherwise I wouldn’t have that bond. But if I did, then they honoured me. I mean, they realised that it would be a disaster if they let it happen.

I also want to bring this good and evil thing in because I was looking at Mary’s book and I saw this very startling picture of myself dressed as one of the Rippers. Jack the Ripper. And I was thinking, what were we playing with there? What was that about, this is violence against women?

Do you know where I was? I was up in a flat above, looking down. And all the people up there were Arts Council people. The flat of Adrian Heath, the painter. So I knew him. So I got access to it to look down on what was happening. And I could see what was happening. And I said to the audience in the flat, I said, I’m just going down to turn round the audience. And they looked at me and said, turn around. Wow! So that they could have a better look at what was going on. And I went down and moved the rope. Just by moving the rope, it moved the audience. So that the upstairs window could see what was happening.

But it was serious. We had two mirrors. And it was about that, the two mirrors reflecting what was going on. So it was like looking into the mirror and seeing another reality. That’s what it was about. It was a philosophical approach and an artistic approach to it. So that was the aesthetic. It had the moral right to perform. That was important. And the performance was conducted in such a way that it had a geometrical structure of figures moving in space. So it was both a drama in space and an idea behind it. According to the mirrors. And why the mirrors were used. If Jack the Ripper approached, he would face the mirror and see himself. And see himself doing some harm to people. I’ve got a book with about 20 or 30 outlines of performances for Action Space. And they were quite detailed, saying, entrances and exits and structures. Some idea of the title of the piece, what it was about.

I just think that in terms of depicting things, particularly political and historical things, using them for the dramas that we set up around the structures, one of the issues for me with Action Space was sometimes this can lead to a form of burnout. Sometimes there was too much. Too much in-role emotion and action, that it becomes too powerful. It goes out of control.

This is my painting. I can be terrified with painting. When images occur, quite kind of almost by magic, they come through the paint. The way I use paint is that I manipulate it so that it is allowed to speak for itself. And I think that’s what happens in any kind of drama. You go into a drama as a character or another personality, and that personality takes over and you step into it, but you know you’re in control. And I know I’m in control or with paint, but I’ve made a video recently, asking the paint to tell me something. I’m putting it into the Dada thing in St. Ives, and it’s saying, tell me. Tell me, show me how. What can I do? Tell me, please. I need you to tell me what to do with the next image, and that’s done in a very dramatic way.

It’s very powerful because that’s kind of a principle of painting and really allowing your instinct, intuition and imagination to come through to play with this. And play in Action Space is very important. So this idea of play, which you can get from Derrida and Heidegger, how important it is, because it’s the imaginative creativity. It’s not just being creative, it’s the creativity of play, which a child knows about intuitively and is drowned by successive years of education. And so that’s why playgroups are important and why we were interested in playgroups. It works.If you go in with the strong idea and you’re quite buoyant yourself, you know you’re going to enjoy it. And you know that. You know that the audience are going to enjoy it. How do you make it work? That’s the thing. So your entrance is important. It’s like any kind of drama. Entrance, or the first sentence in a book, first, where you set the scene. So if you set the scene, then you can go on from there. But if you don’t set the scene, it’s weak.

So you had to be very strong. And that’s what we did. The strength, actually was partly the inflatables and partly the voice. And I had a voice, if you remember, and I could go into any situation and talk to people in such a way, in almost a shorthand voice. You use your voice. I used the vehicle, I remember driving the ambulance around a field and we had the audience all set up already there because they’d been advertised. The whole thing had been advertised. We went round this field, I circled it twice, sounding my horn, making a noise, pulling up, got out and said, ‘Hello, everybody!’ and said, ‘I want young children to come here with me to help unload this van!’ And they came. I got their confidence and they worked with it and then they were excited.

When it blew up and everything, same thing. So it was easy in some instances, but another instance, yes, it was a bit difficult often, You need to plan, which is we talked about it, we got together, the group members, the meeting, remember, you’d meet about it, how to do it, where to enter, who had roles and so on, and who handle the sound or the fans, the electricity, the cables. Everybody had a role to play as well as their own role as a specific character. Then they could be individuals or we could work together as a drama which was sometimes spontaneously exploded.

Yes, I remember that.

So that was how we did it. It’s actually the mechanics of how such an operation should happen. And I believe, I mean, circuses know how to do that, outside entertainers know how to do that. But we were more than that. We were an art group!

You can visit the Action Space Archive at the University of Sheffield, UK here

[Read Part I of this interview here.]

[Read Part II of this interview here.]

Rob La Frenais is an independent curator, artist, writer and lecturer and works closely with artists on original commissions. He founded Performance Magazine in 1979 and became an independent curator specialising in performance and installation in 1987 and continues to work and write internationally.