Renowned US performance artist Marilyn Arsem has created over 200 performances and installations since 1975, when she also founded Mobius. Inc in Boston, which has presented thousands of artists’ works in its 50-year history. She is known for leading intensive workshops, more like masterclasses, on durational performance art.

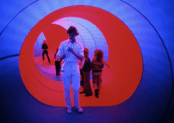

Curator and writer Rob La Frenais, who has recently returned to performance work, participated in her Considering Time in Performance workshop at Milford House, the home of Live Art Ireland in rural Tipperary. The workshop culminated in each participant devising a three- or four-hour durational work presented to the public and some pictures of these are shown with this conversation. (Descriptions of all the works are here). She is soon about to lead a workshop On Practice and make a new performance in London as part of Future Ritual‘s festival Ceremony. Rob La Frenais started the conversation by asking about the headlong political chaos engulfing her home country, then moved on to recall the actual workshop experience itself, discussing the nature of time and the meaning of performance art.

*****

So, how’s the craziness?

Marilyn Arsem: It’s pretty harrowing. There are five to ten horrific things every day that Trump and Musk and their henchmen are doing. I’m going to be performing in London in April as part of Future Ritual’s event, and I’m trying to think about what kind of art I can make now, when I’m living in a collapsing country. I think that all I can do now is design a structure and then leave the choice of my actions open until April. How can I know now what the world will be then?

My original questions have been slightly eclipsed by what’s happened in your country.

Let’s not think about that for a while. I’d love a break.

Going to your workshop we all did together back at Live Art Ireland in June last year, it seems like a long time ago. Those exercises for considering time. How did they develop from your own performance practice?

That’s a complicated answer. I’ve made a lot of performances, and I’ve been making durational work forever. When I was teaching at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, I regularly taught a class on durational performance. So the exercises have been developed over a long time, probably over 20 years. But I keep tweaking them, based on my own experience of performing durational pieces, but also on how the participants in different workshops have done the exercises.

I try to design exercises so that the artist has a lot of leeway in how they interpret it. There might be technical requests, but I rarely talk about content. In fact, there’s only one exercise that you did that actually had an element of content. You know which one that is, don’t you? It’s the 30-minute walk across the room. Besides the technical problem of NOT working in slow motion, but simply going slowly enough, with pauses, to take the full 30 minutes to move across the room, I also suggested that you think about the notion of leaving. That is content. Nevertheless, there is space in that task to do it in a way that allows you to think about your own life.

Yes, it was very impressive to realise that I could actually do it. It’s the first time I’ve ever done anything like that in my life. So, generally speaking, we were a mixed group of different artists, and in my case, a curator going back to being an artist. How did we do as a group compared to, well, you were in another workshop in London shortly afterwards? Be honest.

You all were great! What I really love is to have a broad range of people in age and backgrounds, because they bring to the work different perspectives, and that helps the other artists reflect on their own choices. I’d much rather engender that conversation, or private writing, reflecting on all the possible choices that people can make in performance, and on choices that are often so different from your own.

So we’ve been at a very evocative place. Milford House (the home of Live Art Ireland) which was this old mansion that had got a lot of history to it, even having been an IRA hideout and various things. How did the environment affect the kind of exercises you chose to give us?

It didn’t so much change the exercises per se, but rather the environment affected the choices that the participants made in what they did in the exercises. Participants were inspired to work with the historical content and in different sites, especially in their final performances. The opportunity to work outdoors, and within very different kinds of spaces challenges our understanding of space and time. Think about how you feel when you can look up into the infinity of the sky above you, or when you have the opportunity to walk for miles through the fields. It gives you other ideas about how to make actions in public.

The artist I was partnered with (for the final performance) who was a much, much younger artist, did a very interesting historical performance with the spinning wheel. So you did allow people, I think, come with the things they had in their heads already, but they were changed by the exercises. Moving to being a bit personal. I think the expectations of who comes – for example myself – had quite a lot of trepidation, of just literally handing over my day to somebody who I hardly knew, and say, you know, okay!

Thank you.

So I suppose the question here is, how do you come across different expectations from people? I mean, I had a problem with it in anticipation, but once it started, it seemed to be perfectly natural. But how do the expectations work? Generally speaking, do you have any interesting experiences or stories that might feed into that?

An early exercise that we did was estimating the time of different types of actions. I also use it as an exercise for the group to get to know each other, through play. In another workshop that I taught, one of the participants had to take time off from their job to be with us. They were initially ambivalent about the value of what we were doing, how useful it would be, and whether it was worth losing their income for that period. They questioned the value of the playful aspect of that initial exercise. I ended up speaking about the value of play, about how much we learn through play, and that pleasure is not a terrible thing to engage in with artmaking. It was probably the first time I had ever talked about, articulated, the value of play.

But those early exercises are a way of helping the participants feel comfortable with each other, and to be willing to take risks together. If you do something goofy in front of someone, then you are probably more willing to take other kinds of risks later. These initial exercises are intended to build camaraderie in the group, to engender trust between people, and to encourage a willingness to try something new that might not necessarily work. It’s one way to learn that you can take risks in public with an audience and establish a relationship with them in which they are supportive and forgiving.

Those first exercises also allow me to gain insight into the participants, not just by seeing their sense of time but also seeing the choices that they make for actions to do with the others.

We had some interesting experiences where you were able to manipulate that. I suppose you could say that if somebody went to all your workshops they wouldn’t be tricked.

I have had people repeat the Considering Time workshop, and even when they know the structure of the exercises, they have actually paid even more attention to what impacts their perception of time.

How about the art and science aspect of this? Because if you can show that people have a different perception of time, how does that that connect with our scientific observation of time by physicists or cosmologists, or people who really are looking at Einstein’s theories. Have you had those kind of dialogues about the way you’re able to manipulate time with scientists who question whether time is, in fact, a constant?

I haven’t so much talked with scientists other than people in my own family. I come from a family of scientists. So, I’ve talked about time with them for sure, including my brother, who is a thermodynamicist. Or, as he once described himself, a metaphysicist who incorporates metaphysics into mathematics.

What does he have to say about the flexibility of the notion of time?

His short answer is simply “Time has to do with how energy equilibrates.” He dismisses notions of time and space and the big bang theory, for instance, and simply says, “Energy is eternal, energy is change, and it existed before time. Change is continuous and infinitely differential. It has no beginning or end.”

I admit, when he starts to talk to me about the mathematics behind it all, it definitely goes over my head. By the way, he is also an excellent painter as well.

But I think some scientists do question or consider the human notion of time as being artificial.

I have also read many books on time. When I did 100 Ways to Consider Time, an important aspect of that work was that every day’s performance lasted six hours. But depending on what I did, it felt completely different. It was useful to have that one constant as part of the structure.

One of the days I read aloud Einstein’s Relativity: the special and the general theory and discussed it with the audience for the six hours. I read other books out loud during those performances, including ones on time and space, stars, black holes, and deep time. I read texts by Stephen Hawking; The Life and Death of Stars, by Kenneth Lang; and a very interesting book by Adrian Bardon on Western concepts of time called A Brief History of the Philosophy of Time. I never did find a book on Eastern concepts of time.

I can’t say that I fully understand all those writings. I have trouble wrapping my head around the concept of infinity, for instance.

We’re both at a point in our lives where we’ve done seven decades. How does that affect in your case your concept of time? Has it changed since you were younger?

Now, that’s an interesting question, isn’t it? There was a long period when I behaved as if I would live forever and had all the time in the world. Now I’m much more careful about how I use my time. And I’m much more willing to do less, taking my time to enjoy it. I don’t have the ambition I had. It allows me to let things go in their own way.

Another artist who is about our age, Laurie Anderson, has very famously become a Buddhist. And I’m wondering if you have ever had any inclinations towards that kind of thing through your practice. Could you make any comment about Buddhism, if there’s any connection?

I remember that I was actively reading about Buddhism in my late teens and early twenties. I would expand on that just to say that growing up in the Unitarian church, we studied many other religions in the world, and that included their concepts of time. I think that since a young age I have always been interested in how time operates. Or how we live in time, or through time.

I was doing durational pieces in the seventies, though they weren’t identified at that point as ‘durational.’ It’s only looking back at my work that I see that I have been examining the same questions about time always. So, while I don’t actively practice Buddhism, I think that the degree that I absorbed certain concepts within it are reflected in the work that I do.

Another aspect of time I remember from the workshop, being late back to a session and you said that we had lost time that we will never get back. What exactly did you mean by this? Does it mean specific nature of time in your workshop has a different value to the time we had wasted?

No, in that context it had more to do with the fact that all of the work we were doing was as a group. We had to wait until everyone got there before we could begin, which meant that someone being late impacted everyone’s time. And since I had calculated how long we would do different exercises in order to fit them into the allotted period for the workshop, I had to keep adjusting the timings of the exercises.

Well, I get that practically. But you said this thing about we’ll never get back that time.

Oh, that’s true! No, you have less and less time in the world. Period. You know that at the end of every day you have one less day that you will be alive.

Even if it’s just a few seconds or a minute?

Yes. Use it wisely.

So that would imply that we have a finite amount of time. But then we don’t know when we’re going to die. So I’m just interested in the reflection that you had on the fact that expression had, because you used it several times in this workshop making us think about the finite nature of time.

The finite nature of our time.

Okay, time as a group as opposed to time as each person.

No, even more specifically, the time that each person has. You don’t know how much time you have left in this human form. We can put it that way, too.

I found it was interesting, because we kind of got used to it a bit like monks having prayers at a certain time. We got used to the fact. That you specifically measured everything we did with the little (timer) device that you had. It actually introduced a sort of stability to what would otherwise be felt like, feel like kind of quite long durational bits of time. How did you develop that idea? And what can you say about the idea of being very, very specific?

Most specifically, you’re referencing timing discussions after exercises, right? It has developed over the years. But I do have an early teaching memory of being in a class at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts where I recognised that there were certain students who would dominate class discussions, essentially highjacking the class’s time to focus on their own needs.

It’s a levelling device.

I realized that one person comandeered the discussion, it meant that the quieter or shyer students didn’t talk. By expecting each person to speak, and by limiting the time that they have for a response tends to make everyone much clearer about what is important to say to the group about the work. Of course, it is still coupled with the private writing that everyone does, which are reflections on the personal impact of the work which is often less useful or appropriate to share with the group.

To be continued.

[Main image (starscape) by Pixels/Pixabay]

Rob La Frenais is an independent curator, artist, writer and lecturer and works closely with artists on original commissions. He founded Performance Magazine in 1979 and became an independent curator specialising in performance and installation in 1987 and continues to work and write internationally.