In 1985, in a new introduction to his novel, Queer, William Burroughs wrote: “The death of Joan [his wife] brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and manoeuvred me into a life-long struggle, in which I had no choice except to write my way out.” (Burroughs, 1985)

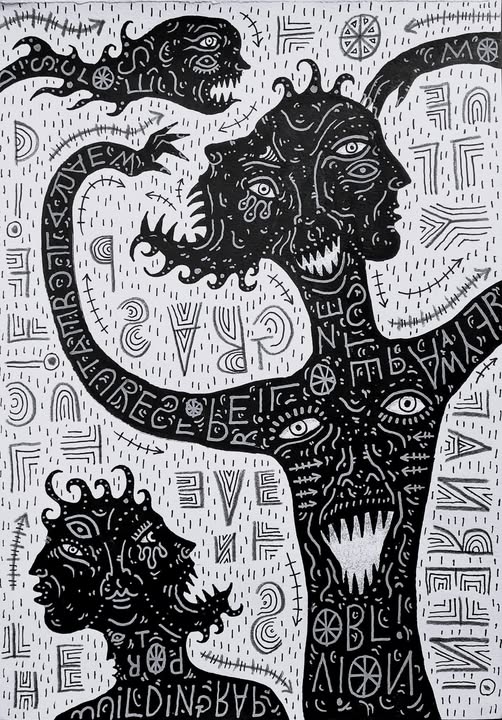

Something like the Ugly Spirit pervades Greg Bromley’s art, but he calls them “dread devils” – shapeshifting monsters embodying threats, fears, anxiety, distress. His burn-out after decades as a social worker and mental health caregiver clearly drove him to express these feelings, to tame his demons by trying to depict them: “Instead of being in it, I’m looking at it,” he explains. (Bromley, 2024b)

Projecting the demons onto paper separated him from them, at least enough to ponder what he’d been through. “I experienced workplace trauma a number of times whereby I was at risk of assault, or on a couple of occasions feeling like I might be killed… By illustrating these trauma narratives, I was teasing them from my mind and removing their power.” (Hodge, 2023)

Illustrating might suggest literal representations of specific situations, but that is not the case. There are secret references to specific incidents, but the images are made fantastical in response to the cumulative emotional impact of dealing with crises in other people’s lives. That partly explains the shapeshifting and composite anatomies of his devils. Bromley treats them as self-portraits.

His degree dissertation included a small but pivotal drawing:

“I made this image in response to module material pertaining to the concept of vicarious trauma. I had a profound realisation that my burnout as a social worker had a definable cause, and the discussion around vicarious trauma had opened a Pandora’s box of reflection… this simple image reflects a couple of metaphors for how I felt about this realisation. The character is falling, it looks like it has tripped over, or it could be that the character is laying prostrate on the floor. This is symbolic of how I became as a social worker; I had fallen. The head looks as though a mask (possibly the mask of the social worker) has slipped as the retrospective-looking head now sees what has tripped the character – the shadow of vicarious trauma is written on the body…” (Bromley, 2023, page 27)

The figure in that drawing is alone, with a blank background. But adding a second or third figure invites speculation about their relationships or an explanation of what brought them together.

Posca acrylic markers and pencil on heavy paper

The addition of collage for colour and texture – as well as drawn ornaments and word fragments (“language dust”) – gives the demons a context – not a place so much as a vague fluid hybrid space, which over time grows more assertive, pushing at the figures as if to swallow them into a place behind the collage. Like Burroughs, Bromley uses cut-ups and collage to form relationships that are only partly intentional and thus not completely tame. “Whatever manifests in the image is what needs to be known,” he says.

In “Never the Twain Shall Meet Met”, two multi-headed creatures with red-hot tentacled bodies are in confrontational dialogue – not exactly a fight, as there is still some distance between them. Their bodies are stout as tree stumps, strengthened by black outlines and cellular partitions. They flash pointed teeth. Each seems a composite, hosting half a dozen heads which don’t agree. So not only do the figures seem to argue, they suffer from internal dissent. Tiny arrows with cross hatches flow around the figures, as if describing winds or ocean currents. Larger black arrows carry words. One says “STATE OF FLOW”. Another says “SUM OF ITS PARTS”. Another reads “TOO BROKEN”. Like zen fortune cookies. This painting was reproduced on the cover of the International Journal of Art Therapy’s special issue on trauma (March 2024). (Bromley, 2024c)

In a letter to a collector interested in the how and why of his work, Bromley described his evolution:

“Nobody I have known in my personal life gives a shit about art, and where I grew up you would get the piss taken out of you if you referred to making art as a teenager (1980’s).… I started making art obsessively in 2011 after my dad died, and during a stressful period as a social work team manager. I was totally mindless about the reasons for making art during this period… Whilst at times the escape has been liberating, it has also equally been a descent… since training as an art psychotherapist, and really digging down on my personal expressions…, I have realised that the artifacts I make are in fact messages to myself.

“My figurative compositions are a consequence of 20 years working with hundreds of people in profound and cataclysmic distress. Social work really is an incredibly hard job… Much of the work is crisis intervention and… repeatedly interfacing with other people’s trauma, over a protracted period, eventually manifests as your own trauma… I think the art making during this exposure provided some relief to my professional experience, but I also believed that I was sublimating the raw feelings into an image, providing me with a sense of exorcism.”

— Greg Bromley (quoted in Hodge, 2023)

“My initial paintings/artifacts were naïve characters (which reflected my limited skills) set within cosmic compositions. I made them big, on thick MDF wood. I used homemade collage, blowing up aspects of photographed B&W drawings on colourful collages… . I moved very quickly to large canvases and started using abstract backgrounds to create the bodies of creatures, adding features with collage and words… They were my inner demons, whispering, biting, and undermining me. During my art psychotherapy study I dropped the B&W characters as I no longer needed them, they didn’t represent my inner world anymore…

“I moved up to Scotland in 2021 and started an MSc in Art Psychotherapy in Edinburgh… During these 2 years of study, I became so much more enlightened about myself, the reasons why I make art, and I developed a much sharper focus to my oeuvre. Whilst studying to be an art psychotherapist I was also in personal therapy (still am), and again revelation after revelation flooded my senses…” (Bromley, 2024a)

Words broken into individual letters appear in all of Bromley’s paintings. He explains this as representing language failure due to emotional overload, and equally the result of a clash between wanting to explain the image, and at the same time not wanting to explain it – confusion about whether it is better to expose or bury smouldering thoughts. He resolves his uncertainty by having it both ways – leaving clues in plain sight, but scattered and obscured. “I reverse and invert letters to make the words less obvious, requiring greater scrutiny from the viewer.” Interestingly, he distinguishes between words inscribed inside his figures and words in the space that surrounds them. The interior words are “metaphors for how we define ourselves [that] prevented change, crushed hopes, and perpetuated the sense of being frozen in the headlights of trauma.” Words in the background are “internal dialogues [that] escaped the coherence of speech bubbles.” (Bromley, 2023, pages 40-41)

Most of Bromley’s devils have jumbled anatomies with multiple eyes and mouths: they are prepared to surveil or bite at any moment. Thorns and sharp curls protect their bodies. They are monsters, but also stained-glass colourful and intricate, inviting study. On closer look, their insides become cavernous and jewelled.

Bromley now recognises humour as an antidote to awfulness in life. “My characters are redeemed by humour. There is a quality to them that I find offsets the darkness… Humour is the light”. (Bromley, 2024a)

His images are layered, in meaning as well as literally, with pen-marks, paint and cut paper defining gerrymandered contours. They are ornate but grotesque, poised but delirious, with a folk-punk quality that has made Bromley a star in the world of “outsider art”. Yes, he is self-taught, but he is hardly a primitive who lucked into a saleable style. Seeing his work in a group show of outsiders (which is mostly how he’s been seen so far), you realize immediately that he is different. He has absorbed Basquiat and added intelligence. He absorbed Picasso and added urgency. He is still absorbing indigenous art and making it universal.

REFERENCES

Bromley, G. (no date) The Cosmic Wormhole (website). Available at: https://www.cosmicwormhole.com/

Bromley, G. (2023). The Monsters of Metaphor. Master’s degree dissertation, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh.

Bromley, G. (2024a). Unpublished letter to David.

Bromley, G. (2024b). “Out of the Shadow of Trauma”. Interview recorded 2 December 2024 and 1 January 2025.

Bromley, G. (2024c). International Journal of Art Therapy, 29(1), cover. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rart20/29/1

Burroughs, W. (1985). Queer (1985), Viking Press / Penguin Books, page xxiii.

Hodge, M. (2023). Bromley interview for “Where there is art there is light” (online exhibition, 21 September 2023 – 24 January 2024), The Outside In Collection. Available at https://outsidein.org.uk/exhibition/where-there-is-art-there-is-light/

After writing feature articles for Artforum in the 1970s, Robert Horvitz joined Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before relocating to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at museums and galleries in Europe and the US, including MoMA in New York and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.