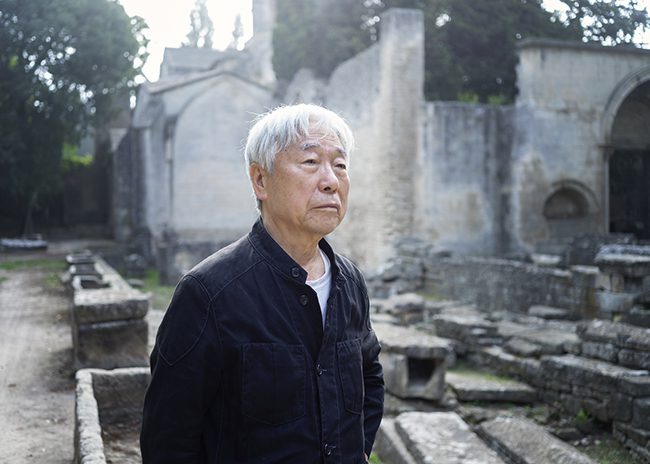

Lee Ufan came to prominence in the late 1960s as one of the major proponents of the avant-garde Mono-ha (Object School) group in Japan. He is known for his minimalist sculptures and paintings, which explore the relationship between mark-making and omission, occupied and empty space. This Spring marks the opening of the Lee Ufan Foundation, a permanent exhibition centre for the artist’s works in Arles.

Here, the artist speaks to Millie Walton about his working processes, posture and repetition.

Before you begin making a work, is it necessary for you to prepare yourself mentally, or physically?

Before I begin my work, I practice basic stretching exercises and deep breathing to soothe myself both mentally and physically. That is my long-term, trained habit.

You paint by lying above the canvas, on a wooden board. When did you first start using this method and how does it affect your relationship to paint as a material?

Since youth, I learned to work by either bending my back or sitting. These postures define my attitude toward the object, namely how my body responds to the object, as opposed to my ego directly facing the object. I value such a relationship between the two more than my own ego.

Given your close perspective to the canvas while you’re working, are you often surprised to see the work when you step back from the canvas?

While working, I sometimes step back from the canvas to see how my work has progressed. That is the moment when my ego kicks in, so I sometimes close my eyes.

What was the starting point for your recent series of paintings Response (shown at Lisson Gallery, London from 16 November 2021 to 22 January 2022)?

The concepts of “encounter”, “dialogue” and “response” largely share a common meaning. Now that a long time has passed, I would like the concept to be the resonance exchanged among everything.

How often do you scrap a piece, and begin again?

In my younger years, I often scrapped my work to start over. These days, I try to complete most of my work but still scrap one out of ten unfinished or even finished pieces on average.

What guided your colour palette for this latest body of work?

I do not have any specific criteria for my colour selections. I feel that my colour palette was mostly light a decade or so ago, whereas it is darker and cloudy these days.

How important is the repetition of gesture?

Right from the beginning of my creative process, my production has always centered around repetitions. Unlike the repetitive movements of a machine, those of a human intend to achieve better results by relentlessly honing and enhancing one’s skill. These incremental improvements enable me to continue my work.

Where do you see your sculptural works and paintings interconnecting?

Sculpture works are about materiality and external space, whereas paintings are about concepts and internality. Yet, both art forms are in a mutually complementary relationship.

In what ways does your writing inform or inspire your visual art?

Basically, writing and visual art are two different things. But I think somehow they might mutually influence each other.

How do you think your approach to making art has changed over the years?

I am not conscious about any change in my own approach to making art. Nevertheless, I notice that my recent art pieces display more diverse approaches than in the past. Perhaps my consciousness has gotten a bit lax.

Featured image: Lee Ufan at the Alyscamps, 2021. Photo by Claire Dorn. © Lee Ufan, Claire Dorn. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.