[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]magine there was a law machine that could swallow ordinary people’s ideas and transform them into legislative proposals written in official legal language. The machine would look like a large sculptural construction with a system of pneumatic tubes that sends all laws written by people into specific reception boxes, each of whom is dedicated to a specific area: gender equality, climate, education, the right to privacy or to free speech. Well, such a machine does exits and is part of Law Shifters, a participatory itinerant art project conceived by Danish artist Stine Marie Jacobsen.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Law Shifters, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, 2018. Foto: Per Wessel

Until May 13th, 2018, the machine is installed and available to be used at Nikolaj Kunsthal in Copenhagen – once one of the oldest churches in the city, today a leading center for contemporary art. That’s not all: the new law texts that will come into being will be on display in Strasbourg from April 4th to May 11th in occasion of the Danish chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. Art and politics hand-in-hand.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Law Shifters, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, 2018. Foto: Per Wessel

Along with her engaged and prolific art practice, Stine Marie Jacobsen has questioned how far a certain given structure (language, legislation, media or others) should go in regulating our behaviour and society. Starting from the premise that we all have something to say, but we might not be able to communicate it, her projects depend on the audience’s contribution and act as enabling platforms for people to initiate their own dialogues.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Law Shifters, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, 2018. Foto: Per Wessel

Interview: Paola Paleari & artist Stine Marie Jacobsen

PP: There are many aspects of your practice that I find fascinating, I start with the first: irony. Your works address very serious issues, but you seem keen to defuse them in favour of a larger accessibility of discussion. For example, in the video that is part of Do you have time to kill me today? (2007), you act the part of a blonde driver who is constantly attacked from the backseat by an elderly man (in fact, your neighbour when you lived in Los Angeles), with the purpose of reworking the normalised scripts of victim and perpetrator roles. What is the reason behind this approach? What are its pros and cons?

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Do you have time to kill me today?, 2007

SMJ: A humorist approach places any didactic or patronising element in the background. Which unfortunately a lot of people still find art is doing. Accessibility is important to me, because the content I work with is often also of interest or importance to a broader audience. I often use humour to create this accessibility for a non-art audience in my projects. Even though a lot of my works are humorous, they are really dead serious. You would know this if you heard me talking about it in person. I shift between humour and seriousness a lot. What lies behind this is an understanding and experience of how cruel and insensitive humans can be(come).

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Do you have time to kill me today?, 2007

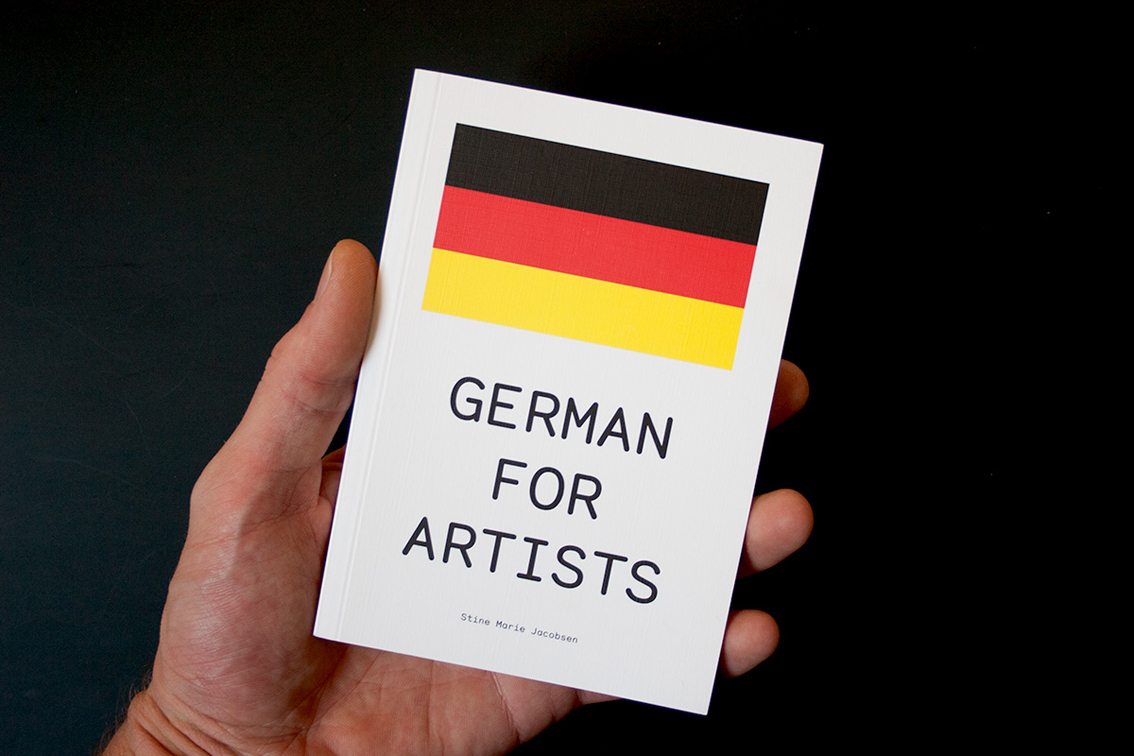

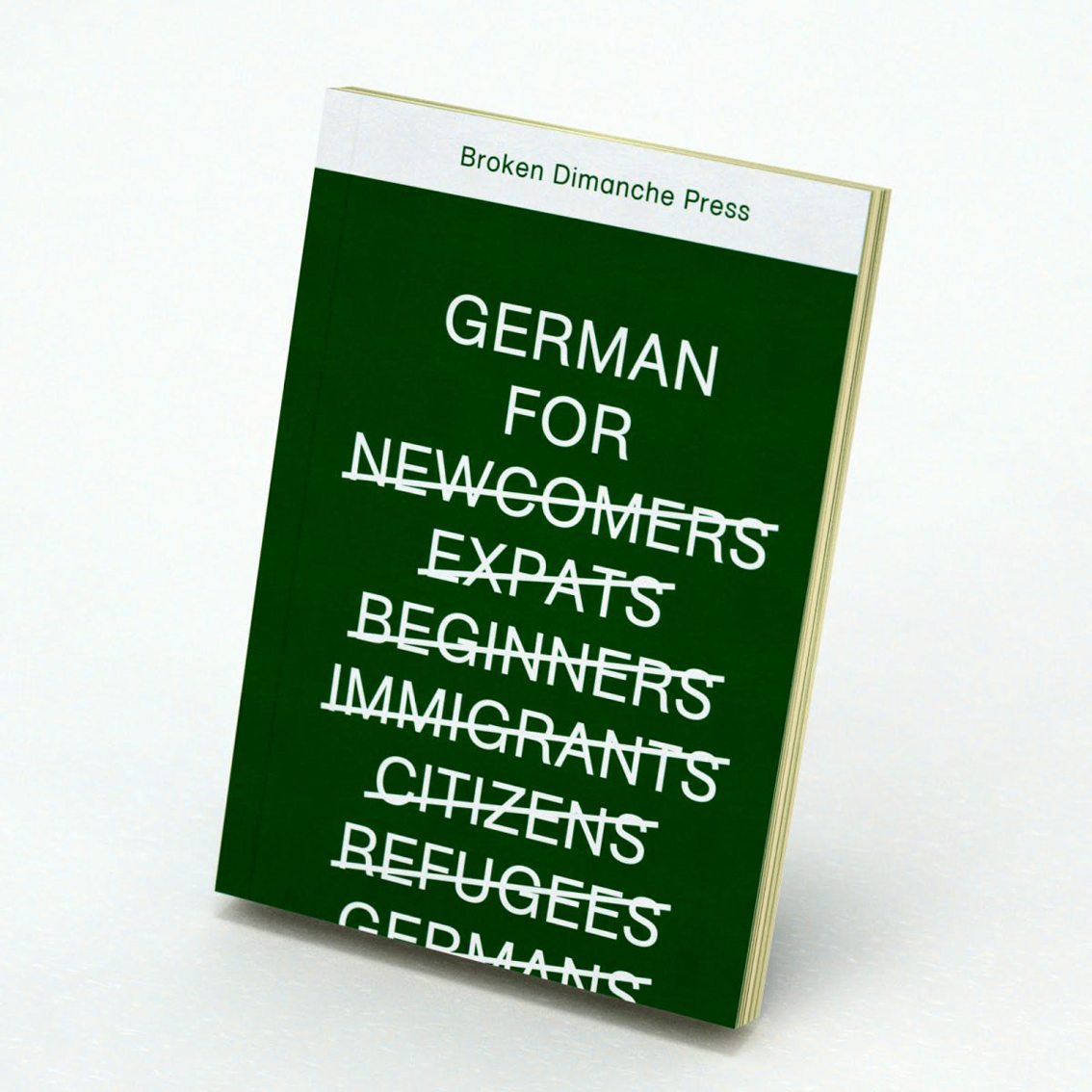

PP: German for Artists (2015) and German for Newcomers (2016-) are based on years of experience in teaching German to expats. Your practice revolves strongly around the idea of language and of its influence in determining our position in society. Notions such as Marshall McLuhan’s in ‘The Medium is the Massage’ or Fabio Mauri’s in ‘Linguaggio è guerra’ (Language Is War) come to mind, but you want to look at language as an empowering tool for the citizen rather than a way to numb the masses. As an Arab proverb goes, “learn a language, and you’ll avoid a war”.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, German for Artists, 2015

SMJ: I also always hope my massages reach people well 🙂

Yes exactly, thanks for noticing that. I think we need to train our skills of argument, because if we want to claim or request something (from our governments, let’s say) we have to be able to explain why. The power of “why” is important. For example, what paragraph § do we want to abolish, and why? Said that, of course we need power to speak and have influence in first place. That’s the hardest part. What’s your weapon of choice, Paola?

PP: Uh, I was not ready to be asked this question back! Well, I don’t know if this can be properly called “weapon of choice”, but I’m in the process of learning Danish as my third language and I can see how multi-layered this activity is, and how many social possibilities and implications, but also political tensions, it contains in itself. I’m definitely gaining a 360 degree awareness while carrying this task out.

SMJ: Your answer is so encompassing and compassionate. It shows that you know that learning a language is learning about “a people”. We actually need to stop arming our words by saying “weapon” when there is actually no gun. To learn a language in these days of closing European borders and a de-globalising world is so important, and that we learn it based on interpersonal relations and acculturation. To shift between languages to feel more yourself when you are being integrated through a language. Nationalism can easily hide in language implementation.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, German for Newcomers, 2016 – ongoing

PP: Another interesting feature of your practice is that the artworks are often presented as embedded in a participatory system or a set of tools. What you create is almost like “strategic design for the visitors”, who are asked to complete the frame you set up for them. How difficult is it to communicate this aspect both to the audience and the institutions, and to make them understand what you do?

Stine Marie Jacobsen, German for Newcomers, 2016 – ongoing

SMJ: Sometimes very difficult… for many reasons. Either the non-art institution and I don’t have the same language or expectations, or I can’t explain my idea, because it isn’t fully developed before I met all the participants or involved people. Communicating with my participants is the easiest part, because I am with them in person and they can directly ask me what I mean. The biggest part of the activity happens prior to the exhibition and when the audience view the art projects, they are invited in either as learners or onlookers – and most of them react like I prefer, that is, by continuing the political discussion and dream scenario; by acting on it.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Direct Approach workshop at District, Berlin, 2014. Photo: Malene Korsgaard Lauritsen

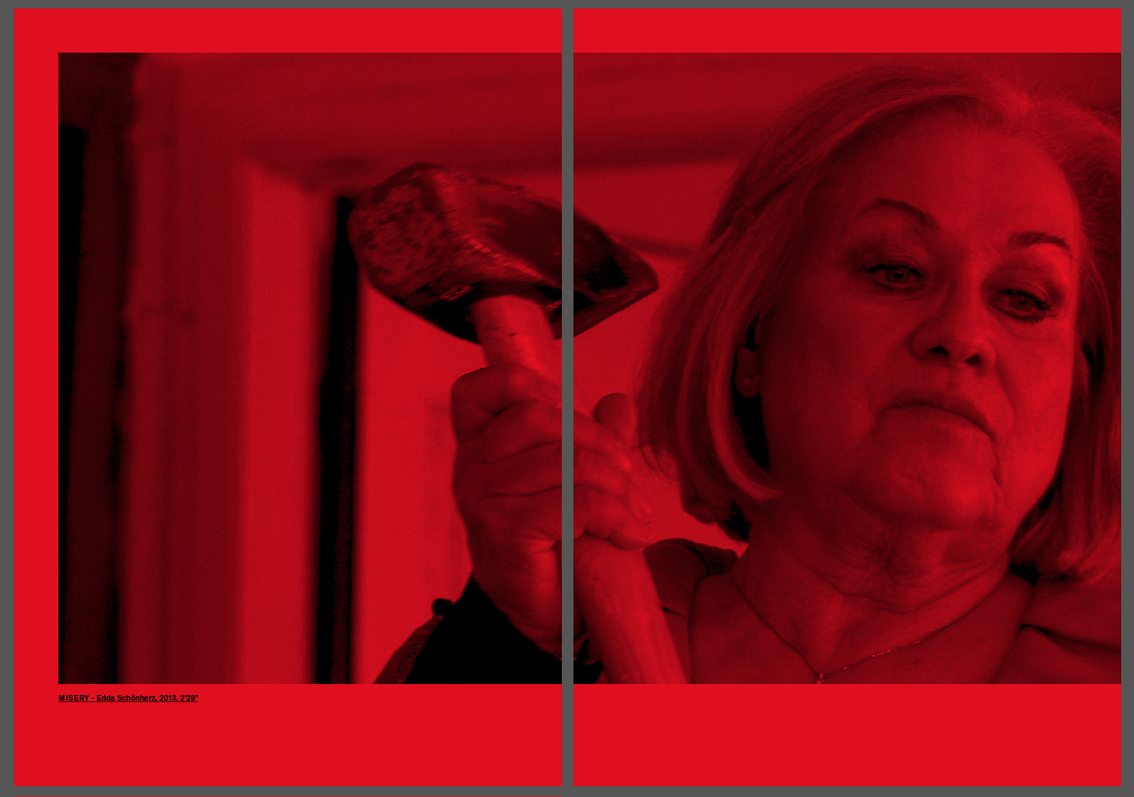

PP: Talking about onlooking: Direct Approach, that you started in 2012, is a participatory art project that aims at mapping civilians’ relation to violence through their identification with self-selected scenes from violent horror movies. The project’s outcome is actually a series of films directed and reenacted by the participants themselves in workshops next one being in New York City as part of your residency at ISCP. More generally speaking, many of your projects have a very strong visual component that draws from popular imaginary, and you often play with the intersections between staged and real life. Where does this particular interest derive from?

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Direct Approach workshop at District, Berlin, 2014. Photo: Malene Korsgaard Lauritsen

SMJ: The outside global world has always presented itself to me through television and popular media. Fiction and reality are very closely linked the violence we see, read or feel in a fiction does in many ways relate to reality. Or the fiction will remind you of what you have experienced. Or sometimes it’s the other way around: people who have lived through violence don’t want to watch it or they don’t want to speak directly about their stories, and use the fiction as a “protective shield”.

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Direct Approach, PSYCHO by Karl Schlarb, 2013

PP: When visiting big art events such fairs and biennials, I often feel a considerable distance between a large part of the contemporary artistic world and the social and political reality it relates to. What are the biggest challenges connected to your decision to squish these two spheres up?

SMJ: Great question. The hardest task now is to change the current attitude from “the activity is there when the artist is present” to a sustainability for art projects. It’s damn hard as an artist, because we are not entrepreneurs and I surely don’t want to be. But I have recently had more collaborators taking over my role and conducting workshops for me. This is a positive direction.

I don’t want to start any NGO, which I have been encouraged to do many times. I would drown in bureaucracy and I would potentially become victim to lobbyism. Relating your question more to the art scene, I often try to negotiate more time. All projects, art and political, suffer from too little time. I have even heard peace builders in Beirut saying that they would prefer less money if they could use them over longer time.

PP: My last question is a recurrent one when I have the chance to converse with a “female artist”: how do you relate to this label, and do you think it conditions the way your work is presented and perceived?

SMJ: Of course it affects how my work is perceived. I can even myself be gender biased in my thoughts. I try to work against it, though. We humans like gender categories and think unequally about gender. I very rarely experience the labelling of “female artist”, but I am aware of how sales and museum archives do not historically favour female artists. Look at general salary (in)equality: the art world mirrors the rest of the world. I don’t need or support any “identity politics” label because it stops a slower understanding of what art is about. Categories end dialogues. What do you think we can do about this inequality?

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Direct Approach – The Guidebook, Antipyrine Editions, 2016

PP: Once again, I think that language and dialogue are key to it. Many things that we take for granted today were taboo until a few decades ago, and if they started being accepted is because people have been talking and talking about them. I agree with you on the necessity of spending time, active time, on certain topics. I don’t think we will be able to experience a real and definitive gender equality, at least within our generation’s working lifespan, but I hope that my children will look at the salary statistics from 2018 and comment: “oh gosh, see that gender wage gap, isn’t it ridiculous?”

Stine Marie Jacobsen, Law Shifter workshop with students from Hjemly Friskole, 2018. Photo: Liv Møller Kastrup

SMJ: Hopefully in the future people will say: “wow, look at that gender go!” when a gender binary person walks by. I agree, we can get there by becoming sensitive to how we use language towards gender in our laws and common communication…. the future is non gendered, slow and rhizomatic. I’m a dreamer, we have a far way to go! But I do recommend, that we talk and work more outside our normal safe art zones.

PP: Well, if we “art people” stop dreaming or thinking outside the box, then we are really only left with procedures to follow! If we look at our position from this perspective, it’s a big privilege, but also quite a responsibility. Thank you so much for this exchange, Stine! Would you like to leave us with some reading or other kind of tips?

SMJ: We are super privileged indeed, we have to be shifters and live as the dreamers,magicians and lovers. Yes, sure, I can share with you my biggest inspirations and some afterthoughts: if you use your audience as co-creators, consider if it is a collaboration or cooperation. This will clear participatory things up a lot.

Names I would suggest to check out if you are into participatory projects are Artist Placement Group; Raivo Puusemp (especially his project The Dissolution of Rosendale, N.Y., which could be called the biggest public sculpture ever made); Group Material; Suzanne Lacy, Annice Jacoby and Chris Johnson for their project The Roof is on Fire.

As for the readings, I could not go without Gordon Allport’s Psychology of Rumor, Allan Kaprow’s The Education of the Un-Artist, Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, John Durham’s Speaking into the Air, Grant Kester’s Conversational Pieces, Helen Fulton’s Narrative and Media and Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells.

Stine Marie Jacobsen is a conceptual artist working to decode violence and law both individually and collectively through participatory means. She lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin, graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts with an MFA in 2009 and a BFA from CalArts, the California Institute of the Arts, Los Angeles, USA in 2007.

https://vimeo.com/stinemariejacobsen

Paola Paleari is an Italian independent curator, editor and writer, currently living in Copenhagen. She is Deputy Editor of YET magazine, a publication dedicated to international photography, and member of FSK – Foreningen for Samtidskunst, the Danish Association for Contemporary Art. Her main area of interest is the photographic language and its relations with the contemporary visual culture and art practices.