T

he Institute of Contemporary Art has, since its founding as a foil to the establishment Royal Academy, sought to present a programme both radical and forward-thinking. FRAMES of REPRESENTATION has quickly become a stalwart of the ICA calendar. Running since 2016, it has grown from a handful of films to this year showing 14 titles selected from around the globe. Spearheading the festival is the ICA’s head of cinema Nico Marzano. Since joining the ICA he has pushed and successfully achieved the move to bring cinema planning back in-house and fostered the success of FRAMES of REPRESENTATION.

This year’s festival was based around the theme of ‘Communality’ and celebrated collective action and artistic endeavor. In the run-up this year’s festival, Nico Marzana spoke to Ruth O’Sullivan about his role at the ICA, and what goes into making FRAMES of REPRESENTATION.

Let’s start at the beginning. What’s your own background? Were you always destined to work in cinema?

My background is actually quite eclectic; my BA is in criminal law because I wanted to be a judge and fight the Mafia in Naples. But while I was completing my undergraduate studies, my passion for cinema grew and I decided that I wanted to pursue a career in writing, curation and ultimately in programming. I then moved over into cinema by completing an MA in Film Studies at Dublin City University, which is a city that I still have a strong connection to.

How did you end up at the ICA?

When I moved to London, the ICA was really the only place to go and engage with the kind of independent cinema that I had always been interested in. I started at the ICA in 2013 when programming was outsourced to an external commercial company. It took me 2-3 years to build a vision from within the institution and convince the ICA that the best course of action for us was to return to being fully independent, which is what we finally achieved in 2016. Since then, we have been able to develop more radical experimental programming. We have also resumed the film distribution arm and founded a film festival, FRAMES of REPRESENTATION, the first edition of which took place in 2016.

What led you to set up FRAMES of REPRESENTATION?

I wanted to create a festival that would be a space for discovery and collective sharing, showcasing films that are not afraid to be daring when it comes to cinematic language. I truly believe that cinema is, in most cases, a political art form. For me, FRAMES of REPRESENTATION needed to become the space to bring this strong connection between aesthetics and politics to the foreground. A place where filmmakers could all come to the ICA to share their films, their ideas and their vision for filmmaking – the conversational aspect of the festival being paramount. These are, in essence, the ideas that informed the conception of FRAMES of REPRESENTATION.

How has it evolved since its inception?

The festival has expanded in size and scope. It started small, with 6 or 8 films in the first edition. Now we are approaching the seventh edition – which will take place between 5-12 May – which includes 14 titles. We will have 11 full-length features and 3 short features that all explore the thematic focus of ‘Communality’. Every year, FRAMES of REPRESENTATION not only presents the most engaging works in the cinema of the real, it also strives to look at different languages. For example, this year we have curated a strand that will embrace all aspects of sound – sound of course in relation to moving image and the films themselves, but also sound as an art form in itself. We will welcome back Radio alHara and Sonic Liberation Front to discuss sound and moving image within the seven days of FRAMES of REPRESENTATION.

What is the process for selecting filmmakers to include?

The films at this festival belong to the idea of the cinema of the real. These are films that depart from reality – certainly – but they also dwell in different forms of fictionalised filmmaking. How we select the films is through two different channels. First of all, either from the research I undertake or from the first 2-3 titles we select, a thematic focus emerges organically, which helps me to shape the programme as a whole. Films also come to the Cinema Team directly from the filmmakers and also from the film festivals that we attend. Overall, the selection is completely informed by the idea of having films that explore cinematic languages and social, political, and environmental issues.

In putting together the programme for this year’s festival, have you noticed any interesting or surprising trends in emerging practices in documentary cinema?

This connects to the reason why I set up FRAMES of REPRESENTATION a few years ago. For me, the cinema of the real – all the films that are between fiction and nonfiction – are constantly innovating, not only in terms of form but also geographically. This edition includes three incredible features from Latin America beginning with the opening night film, Dry Ground Burning, a Brazilian film. There are incredible trends coming from that region, but also all across the globe there is a desire to explore and investigate reality while also taking a very creative stance towards storytelling. This year, I’ve noticed a very strong use of archival material. As part of FoR22, we have Arnaud des Pallières’s American Journal, Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville USA and Eric Baudelaire’s When There Is No More Music to Write, and Other Roman Stories, the closing night film. These all use archival footage but in a very personal, original way, by reworking the archive to create a mode of storytelling that departs from the archive. Every year, FRAMES of REPRESENTATION presents us with new possibilities to create important and exciting moments of discovery for the audience that attends the festival. This year’s theme of ‘Communality’ tells us a lot about the need for collective spectatorship and collective responsibility. It calls for action and looks into the accountability of filmmakers, curators and audiences. As I said, if cinema is a political art form, accountability needs to be assessed across all areas of filmmaking, both behind and in front of the camera.

Why did you decide on ‘Communality’ for this year’s theme and what does it mean exactly?

‘Communality’ resonates as we are finally allowed to return to cinemas to experience films together. But ‘Communality’ also came to me as an image. There was this image of a filmmaker in the middle of a crowd and I could not distinguish whether the crowd was made up of the audience going to experience cinema or the subjects that are framed by the filmmaker. For me, ‘Communality’ is a matter of being together – yes – but also about taking some level of action and responsibility. ‘Communality’ also refers to our space in society, which is not an individual space but one we share; it belongs to a group of people. FRAMES of REPRESENTATION aims to be a safe space for care, solidarity, supporting and nurturing new emerging voices. For this reason, I cannot see a better theme than ‘Communality’ for this seventh edition of FRAMES of REPRESENTATION.

This year’s festival features a curated space and residency with Radio alHara – can you give us a bit of background to this collaboration?

The collaboration started last year with Radio alHara as a sound platform that started in 2020 to display sound material that Dirar Kalash, the Director of Sonic Liberation Front, was gathering when the latest attack of Israel on Palestine resumed. The idea of this collaboration came about not only to give space to amazing sound artists but also to look at how radio and sound can play a major role in connection with the moving image. We are now amplifying this collaboration because in this edition of the festival, Radio alHara and Sonic Liberation Front will be with us every day in the ICA Studio for research sessions that are open to other artists, filmmakers and the audience, to promote collective experimentation. We’ve also commissioned Radio alHara and Sonic Liberation Front to bring amazing opening and closing nights of sound and togetherness to the ICA, on the 5th and 12th May.

How do you view the cinema of the real’s relationship to “truth” or reality?

I don’t feel that the cinema of the real or FRAMES of REPRESENTATION as a festival pursue the idea of truth. For me, the idea of truth is completely personal and is often a matter of point of view. Reality is a matter of opinion. What I’m interested in is not the truth as such, because philosophically, morally and ethically I find it a problematic concept. I’m interested in how filmmakers capture reality. In this sense, reality in the cinema of the real is a concept we depart from. In capturing reality, we might catch glimpses of something that might resonate as truthful with audiences. It’s a relationship that takes different forms and shapes. It does not want to present facts or factuality but represent a point of view.

If you had to choose just one film from this year’s festival line-up, what would you recommend?

FRAMES of REPRESENTATION is always a labour of love and the result of committed, engaged research throughout the year. The lineup not only represents the best of the cinema of the real but is also very interconnected; in a way, the films speak to each other. The festival tries to foreground an overall conversation about different ideas and different languages so it’s very difficult for me to single films out. The festival is also very compact; if we think about the 14 titles we have this year, I think it’s very beneficial to follow the 7 days of the festival throughout the week.

A few key thematics will emerge. As I mentioned before, we have three Latin American titles: Dry Ground Burning by Adirley Queirós and Joana Pimenta, The Delights by Eduardo Crespo and My Two Voices by Lina Rodríguez.

I’ve also already mentioned the archival themes that we will find in a few films: Miryam Charles’s This House, Arnaud des Pallières’s American Journal, Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville USA and , Eric Baudelaire’s When There Is No More Music to Write, and Other Roman Stories.

There’s also an emphasis placed also on family values and environment, for example in Brotherhood by Francesco Montagner.

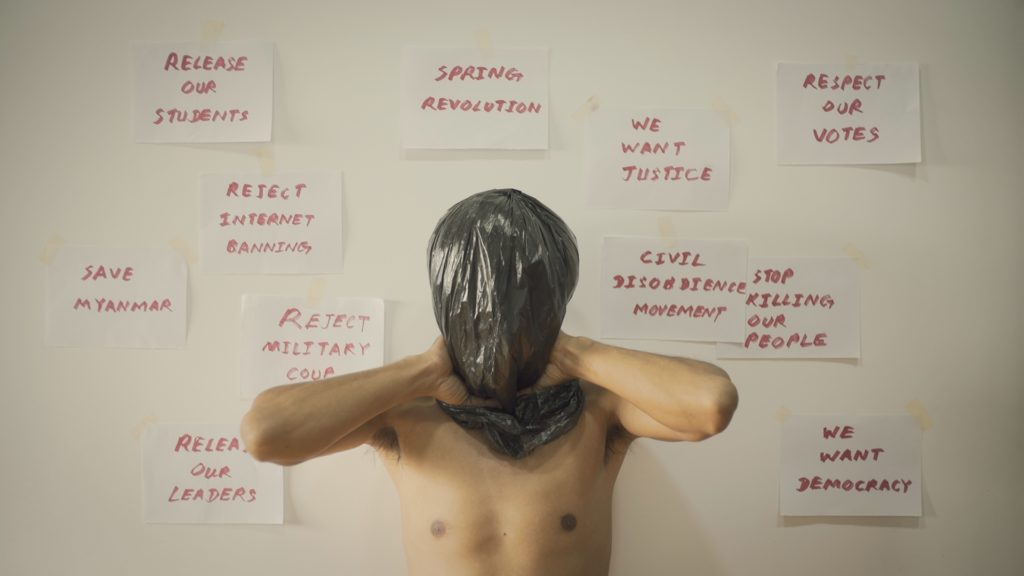

There is an important moment of actual collective filmmaking that will manifest itself through films such as Myanmar Diaries – a collection of footage from anonymous filmmakers about the attempted coup that took place in Myanmar in 2021. We also have We, Students!, which is a film directed by Rafiki Fariala but was made by a collective of students based in the Central African Republic.

Finally, we have an important selection of short films that will look at the cinema of the real – as per our usual curatorial approach – from different points of view; from a more ethereal, mysterious, fictionalised approach to nonfiction to a more observational one.

Current ICA Film Programming can be found here

Featured Image: Dry Ground Burning (Mato seco em chamas), dirs. Adirley Queirós & Joana Pimenta, 2022.

Ruth O’Sullivan is a writer and curator. Her work explores the impact of digital technologies on contemporary art practices and challenging gender disparity within the visual arts.