[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]”B[/dropcap]ut somewhere a piece of our disguise still sticks to us, which we forgot. A trace of exaggeration remains on our eyebrows; we don’t notice that the corners of our mouth are twisted. And this is how we go around, a laughing-stock and a half-truth: neither real beings nor actors.” –Rainer Maria Rilke

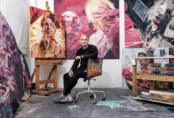

Stuart Semple has become an established artist who reviews ephemeral media images through his painting, placing them in the context of an emotional historical collage. His use of what some might call ‘saturated’ media symbols owes a debt to Warhol and the pop art generation. However the contrast between their work and his most accurately describes the differences between Baby Boomer political egocentrism and Generation Y’s apparent modus operandi of using fame and celebrity as the pinnacle of personal statement. A position that Stuart ambiguously mocks, deifies and defines. At the time of the Fake Plastic Love exhibition he had become at once an overtly celebrity focussed painter and also a media savvy celebrity whose bio reads as a hagiography of a hardworking outsider given an insider pedestal.

While this posturing may appear commonplace, which is precisely his point, Stuart Semple is amongst the most successful artists of his generation as his bio illustrates:

“Commercial success soon followed with Stuart’s London exhibition ‘Epiphany’ (2006) taking over $1 Million in sales. However, it was his curatorial projects “The Black Market’ in NYC and ‘Mash-ups’ at The Design and Artists Copyright Society (London) that caused critics to sit up and listen to Stuart’s argument that “pop culture is a powerful vehicle for real meaning… after all it’s an almost universal language that we are most fluent in”.

The paradox within his bio hinges on his emphasis on empowering hard work versus serendipity or patronage and the elevation of disposable images and icons almost in an effort to ‘save’ fame from the transience of its nature. In Semple’s world the viewer seems driven to ask whether we have failed the fame monolith by being fickle, rather than simply walking away from what might appear to be the shallow, impersonal and exploitative nature of advertising. Given that these images and modes of being are inescapable in a consumer society Semple’s take has to be seen as an empowering one.

Days prior to Semple’s Fake Plastic Love exhibition Trebuchet caught up with Stuart on a noisy East London fire escape to discuss his choice of imagery and meaning in his paintings.

Stuart Semple: I make use of familiar images from the 80s, using icons as well as taking snapshots of things. I think the process of taking snapshots of momentary things, firstly making them strange and then making them permanent through the process of painting.

In a number of ways, it’s not just about preserving them but putting them back to what they were. They were seen as disposable, throwaway, by painting them it is sort of like claiming them back from mass media and putting them back into art again. On a personal level this enables me to make sense of things that I grew up with.

Trebuchet: Revaluating them?

Stuart Semple: When I was growing up in the 80s these things were – I don’t know if it’s quite right to say they were aspirational, but they certainly gave me my first feelings of something larger. But as you get older you get more jaded so now when you look back at these ‘nostalgic’ things, you’ve lost something. Here I’ve tried to look at them again in such as way as to rediscover that sense of feeling.

Nostalgic? Your paintings seem for more forward looking.

Stuart Semple: When you look back at symbols from the 80s, in a way they become rarefied, they become more special. They seem more ‘hi impact’ as opposed to now when things are more homogenised.

But is that the case? Perhaps this sort of nostalgia for a less homogenised, more meaningful past perhaps this is more of late 20s things rather than something characteristic of the 80s?

Stuart Semple: It could well be! But branding is different now. Advertising is different as when we were growing up things did change. Before, people bought washing up liquid based on whether it made their hands soft now people buy things based on it making them sexually attractive. The slant from where brands are more than what they sell is normal now and manufactured pop bands fell in from that and it did make things more homogenised in a way. However, powering it was a real creative impulse, almost a genuineness which is mostly lacking now. Those were the days of dissatisfaction, poverty, the Thatcher years and all that. Now we have the 5 minute celebrity.

Thunder in Our Hearts – Stuart Semple (2007)

This change from functional to moral basis of advertising/branding, the change in advertising from softer hand soap powder to soap powder that makes you a better person, is reflected in this series of paintings? For instance how is this reflected in your painting ‘Thunder in Our Hearts’?

Stuart Semple: Well you’ve got two women and you can’t see their eyes. They’re obvious catwalk models, the Castle Grayskull, Pinky from Pinky and the brain, and a pentagram with a logo in the middle.

[Silence]

So, the pentagram… ah. You made some Alastair Crowley t-shirts didn’t you?

Stuart Semple: Yes

Are you familiar with his work?

Stuart Semple: Yes

…The book of the law…

Stuart Semple: Yes

Does that inform your work?

Stuart Semple: Not at all! For me that is just something I read as a teenager. What I liked about Crowley was his use of symbolism, strong images that are strongly iconic.

Similarly though, your work is strongly symbolic where you use juxtaposed images to convey a sort of resonant meaning by placing different things together.

Do you think that identity is formed in the same way?

Stuart Semple: If we’re in a landscape, a cultural landscape, with strong references to TV it puts the individual in a different arena depending on who they are. Each person has a different cultural make up and a painting might describe who they are. I might be 50% punk, 20% Emo, 30% Castle Grayskull and this might describe someone better than painting them in bark or whatever.

So there are no absolutes when it comes to a person’s identity then?

Stuart Semple: No there is no absolutes. I think for my generation, take Myspace for instance there is a need to update a photo of yourself every five minutes to validate what you identity is. I think people need to see their reflection in something for it to be real.

Is this replacing some other, more physical way of creating identity?

Stuart Semple: I don’t know. Perhaps it has something to do with celebrity obsession where people feel the need to see themselves external media to feel part of something?

This reflects a general sense of meaningless in society as a whole?

Stuart Semple: Perhaps there is certainly something there where people think ‘I physically look like a pop star that’s why I’m as valid as one’.

On eve of what, I think will be a landmark show what do think about becoming a public person. Are you constructing a public persona?

Stuart Semple: I don’t know. I think of people like Damien Hirst and the Young British Artists (YBA) and what they did with their confrontational approach but try and make things, or find something more internal and externalise it. Like using the idea of branding and brand images that works well in that way. I think people have a real distaste for branding as something evil but I think there can be something very artistic it in. Take someone like Andy Warhol who played with image and branding in what he did.

Is that what you aim to do, control an image of yourself as a brand?

Stuart Semple: I don’t think you can control it but you have show something genuine. You can try.

When you smuggled a painting into the Saatchi gallery supporting the YBAs whre you trying to do something revolutionary, are you trying to energise people in the art world?

Stuart Semple: I was genuinely really annoyed. I was thinking ‘what is he on about’ all these artists who he’s championed or whatever are brilliant and suddenly he’s saying that they’re irrelevant or not important. I mean he’s made millions out of it and then to say that it’s crazy.

So does price equal value in art?

Stuart Semple: Well I think there is a point in the art world where it becomes about money and not about work. There is an ‘art world’ where you can put on a show in East London and other artists come and see your work and that’s great and then there is another art world where all the right people attend and the prices go up etc. and then it isn’t about art anymore and that’s the kind of thing that I have a problem with. But then once an artist as a brand becomes more desirable and that sells then the sort of people you become involved with means that it’s more difficult to control your brand etc.

What interests you about brands and marketing?

Stuart Semple: I’ve studied brands a lot. A lot. I like the headspaces that branding gets into. Branding now is very complex. It takes in street art and guerrilla marketing I think it borders on art in a lot of ways. For me marketing is about communication more than anything else and for me as an artist you want to communicate. I mean you paint these things to say something so you look at the ways to get your message across.

It’s been said that the paintings in this show are about isolation and alienation, but then they’re also very accessible.

Stuart Semple: I think they’re accessible because of the language. The language is straight from popular culture. So they are symbolic in a way that a lot of people can identify with them. So in that way I want to reach people not just art world people but a lot of people across the board. I still feel like an outsider in the art world but I am a part of it I suppose in much the same way as people, myself included, feel represented in the world but also separate.

As part of the 2007 Frieze Art Fair the Fake Plastic Love exhibition opened to critical and popular acclaim. The show broke the $1 Million sales mark within the first five minutes and attracted over 10,000 visitors. Reviewers such as The Financial Times describing Stuart as ‘The Basquiat of the noughties’, the Independent newspaper placed him within the top 20 artists and ArtNews drew the comparison between Semple and Hamilton exactly 50 years after the latter had defined pop art.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle