[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]ongs, satire and abuse, The Doug Anthony All Stars (DAAS) defied expectations of the nostalgia trippers, mixing old and new material with a poignant twist.

One of the best comedy performances in recent years, DAAS are still fresh, funny and naughty naughty boys, catch them when and where you can.

In 1996 at the height of their powers DAAS ceased operations. The reason why was never fully spelled out but Fidler has stated that the group had achieved as much as they wanted with DAAS and it was time to move on. Even cloudier are the reasons for this comeback tour, but for fans it is enough to grasp the Chinese burn of Gen X disaffection as they sink apathetically toward the bottom of a coagulating talent-pool.

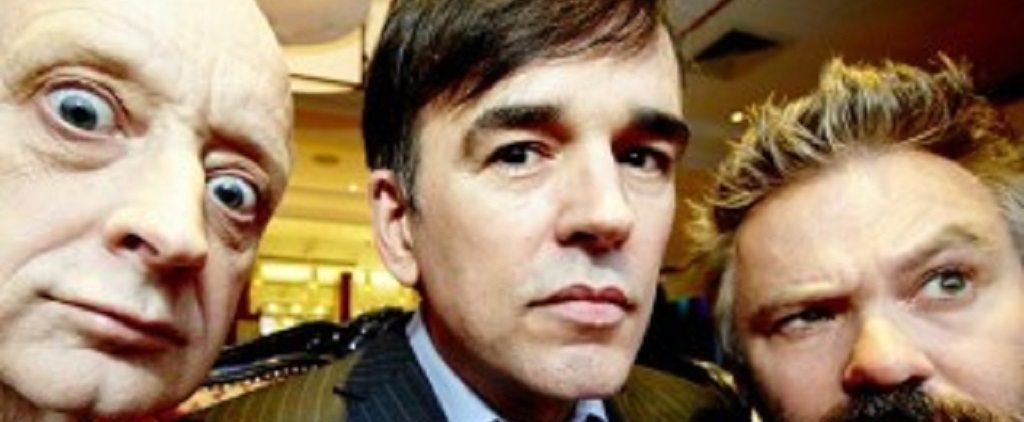

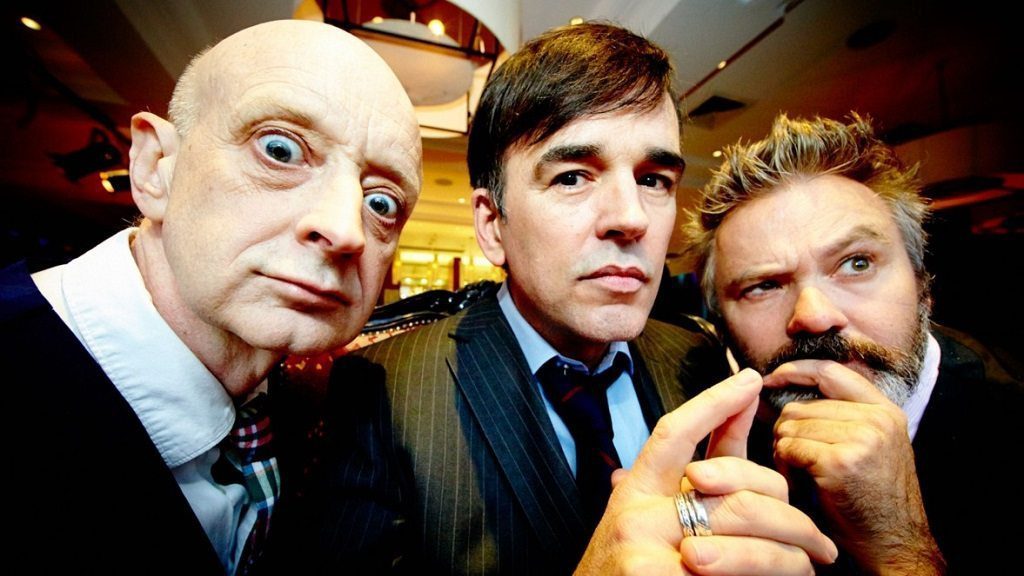

True to his word original Guitarist Richard Fidler (pronounced ‘f-eye-dler’) doesn’t perform with the group, replaced by long time DAAS associate Paul Livingstone, an able accompanist whose childlike persona fills Fidler’s role as a target for the nasty antics of Tim Ferguson (the pretty one) and Paul McDermont (the singing one).

The DAAS format mixed juvenile asides, social satire (especially against political correctness) truckloads of chemic antagonism, sexual out-your-endo, interspersed with comic turns in song. It’s a formulae that still serves. DAAS could always hold a tune, and despite the grey hair their delivery is still tight, and after several jaw dropping performances (including the sublime ‘I fuck dogs’) they still transfix.

Despite the bile and sexual brouhaha, with their polished talent for writing songs and sheer charisma it’s remarkable they never fell into the morass of the Australian music scene. But then, it’s hard to see why they would have wanted to trade being a unique act to be just another group of musos with better banter. In the end they got the best of both worlds, they became what they set out to become: rock stars of comedy

Tall, handsome, and effortlessly condescending to Paul’s tiny angst Tim Ferguson was pushed onto the stage in a wheelchair. Their early 90s output shot down a wide variety of targets, returning often to jokes against the middle class, middle aged and wise youths (their audience). Naturally the wheelchair is a riff on DAAS being old, their audience being old, the sickness of nostalgia and of course, cripples. Tim has lectured about the importance of having tragedy within comedy, of creating an emotional dynamic that allows the jokes to carry further than their first hearing.

As the show wore on through tears of laughter, seamless patter, and Paul deriding Tim’s wheelchair-bound form, we started to wonder whether the seated Tim wasn’t, in typical DAAS fashion, some sort of Brechtian prop gag. The tension stretches beyond comfort until the audience begs Ferguson to crumple into his spastic pose croaking ‘what am I?’… before jump kicking onto his feet declaring with consummate arrogance ‘Still beautiful!’

But that moment never came.

The truth is that symptoms of Ferguson’s MS have now advanced to the stage where he can no longer perform standing up. Not a fact that has been publicized widely in the UK promotional material. As the show drew on you could see people realise the depth of Tim’s illness. Nostalgic memories of a boyish DAAS overlaid onto these men added a worldly poignancy. Time passes, collecting some as hitch hikers and others as roadkill.

I’m sure that at certain points I could see Paul’s eye mist as his interchanges with Tim seemed to catch something. Memories of tackling London in the 90s, triumphs of youth. Will this be the last DAAS performance? Who knows?, but if so, what a show!

From the 80s onward DAAS were surreal and anarchic, skewering cultural tropes high and low but never dealing with their own issues other than those within the billboard-sized personae cloaking each performer. Was there truth in those exaggerated stereotypes? Paul the short angry man, Richard the naïve guitarist, and Tim the pretty, statuesque sex-god? Probably, but only ever enough truth to support whoever the joke was at the time.

As street performers, the DAAS characters allowed people to easily ‘get’ the buskers’ interplay as they shopped for footwear or headed to a Fringe show, which in turn translated with sniper accuracy to the ADHD channel-flipping milieu of global television. Ceasing in the mid-90s, each member of DAAS expanded to projects that showed wider appeal, but muted their cartoonish violence, sexual sarcasm, and satire.

Panel TV, intellectual radio, gameshows; the DAAS boys moved on, found the mainstream, and developed pursuits. They were successful but never quite as funny nor as relevant, ditching the crowd university for the cowed universal, the campus for the capital. In that sense their return is unnecessary and by revisiting the past, tempting irrelevance.

But they kill. The crowd is convulsing with belly laughter. Hands sting from applause. Faces ache. Tears roll. This outing of the Doug Anthony Allstars only needs a basic spark to produce tower of comic flame; they can elevate a fart joke into something vaguely satirical, or as easily plunge into perverse depths. It seems effortless, easy, dynamic, musical, pre-menstrual, post-coital, Australian.

The closing joke is not so much on Tim as giving him the last laugh. The others gambol offstage to ringing applause. Ferguson meanwhile sits, mock frustrated. Eventually they come back onstage and struggle to the push the wheelchair through the curtains. Paul gives up and, walking away, reveals a sign on the back of the wheelchair ‘Fuck my arse, I still enjoy it’. DAAS have long mastered the art of appearing perfectly random only to reveal a long set-up.

Continuing the gag as the audience files down the exit stairs we see Paul struggling to push Ferguson through a side door. Paul cursing and Tim looking abashed. Seemingly stuck with their audience, people shower love and recognition on the pair. Paul beams, administers warm hugs and, as teary fans shake Tim’s hand it feels huge, emotional, and final.

The closing piece of the show included a back projection of the group in their original heyday circa 1996. The ravaging passage of time is very real in the room. Twenty years is a long time for everyone. DAAS belong to a time before 9/11, before the War on Terror, before immigration was a demonic issue, when a leftist PC agenda was seen as a positive step for and by mainstream society.

During the Napoleanic wars nostalgia was classified as an illness that overtook combatants as they remembered past loves and lives far away in distant homes and hearths. DAAS’s main target was always the optimism of social improvement and the stench of nostalgia, both things that various interviews have used to pigeonhole Ferguson’s life with MS into an easy ‘human interest’ story that can ‘aww’ away irrelevance. Tackling that shit head-on, DAAS gave us a great show that footnotes his illness against the larger comedy. MS being another character on stage to mock.

It would be easy to roll out the sentence ‘and in the end Ferguson still stands tall, still beautiful’ and it still works, but not in the saccharine human interest way. It works in the DAAS way, where that statement is presented alongside Ferguson seated, tremulous (though still handsome) where sarcasm and irony ring positive. Tragedy is a subject to use, that’s how we laugh.

[button link=”http://sohotheatre.com” newwindow=”yes”] Soho Theatre[/button]

Editor, founder, fan.