“When I think of art, I think of beauty.

Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not in the eye, it is in my mind. In our minds there

is awareness of perfection.”

– Agnes Martin, from Beauty is the Mystery of Life

To see an Agnes Martin painting is to exist in the mind. At the exhibition I felt this to be overwhelmingly true, but what does it mean? Paintings can be said to be experienced in different parts of the body: Claude Monet’s paintings can make you feel like one big eye, a Francis Bacon on the other hand, as he himself said, hits ‘directly from the eye to the stomach’, and Agnes Martin is a painter of the mind.

I felt so aware of my own thoughts by the time I’d got through all eleven rooms, that when a stranger started a conversation with me about the show, I could think of nothing to say and had to make my excuses and leave, and when I sat on the train home I could think only of my mind and its way of holding images, as though it was folding in on itself like perfectly off-white dough.

So yes, ‘paintings can be said to be experienced in different parts of the body’, but

doesn’t this draw our immediate attention to the inevitable? It is in the process of writing that I’ve discovered what I could not help but do: find ways of expressing ideas about art. Anything can be said about art, it is an infinite kind of invitation, but only by saying anything, by trying to define and comprehend (all of which is inevitable) could I understand how important it is that I don’t.

It was important to Martin too. As soon as she had begun to gain recognition for her work in New York, she packed up her studio, destroyed a lot of her paintings, and moved to the desert in New Mexico. As soon as she experienced what being a successful artist entailed – having your work looked at by more than a few people, and then having your work interpreted by people who would write about the work, she escaped.

This piece of biography, and in fact the paintings themselves, reminded me of the myth of Pygmalion, the sculptor who made a statue of his ideal woman out of pure white ivory. As told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Pygmalion sculpts himself a statue of the ideal woman, and loves it as though it were a real woman. He prays to Venus and she brings the statue to life, but Ovid’s complex poetry always hints at the elision between the maker believing in the life of his artwork, and the artwork itself actually having a life.

Although this creator’s fantasy does come true in the myth – his artwork really takes on its own life – there is always a hint of doubt in the reader’s mind: has the statue come alive or has Pygmalion actually just become so besotted that his own artistic delusion has completely usurped the story’s outcome? The myth warns the reader or viewer of any art, not to let any willing suspension of disbelief slip into blind faith (not that myths need morals, or art needs didactics.) But more than that, it warns against the blinding power of desire: there is a distance between what you want to see and what actually is, even if you choose not to see it.

On that day I had woken tired, and arrived at the gallery early with a head full of little unknowable thoughts. As I settled in front of the first painting, the quiet horizontal lines became the lined paper on which my head emptied itself. I stood looking at the strange distillation of this first room, which seemed designed to reorder the viewer’s mind’s eye. Seeing this extensive survey of the artist’s work is a bit like visiting a mindfulness retreat. I was forcefully made aware of my mind’s shape, previously unconsidered before it hung in front of me, in the form of the canvas.

As soon as an artwork is looked at, it changes, as though it were a myth from the Metamorphoses. It may as well be a blank canvas, as white and pure and Pygmalion’s creation, which is a creation of his mind, and retains its purity by being perceived by the artist alone. Martin’s paintings, often as white as the ivory Pygmalion used to sculpt with, exercise a degree of control and artistic intention that seems to transcend expression. She used mathematical workings to plot her grids and make her marks, and when you stand in front of one, not as Pygmalion, but as an onlooker, the mind morphs this stricture into a mental image, a depiction of what you choose to see within it, like a magic eye image. The paintings ask whether or not an artwork can be seen for what it is. And if that’s even possible, what might it look like?

The story of Pygmalion asks difficult questions of art, of whether or not an artwork can exist ‘as it is’, without traces of the artist or the viewer. Inevitably it gets splashed over with the washes of people through time, their opinions and perceptions repainting the work in a continual process. Yet concurrently, what always remains is the fact of the painting, which is also unchanging amidst all the shifts in public discourse, the flux of taste and criticism. Something of this paradox is important to Martin’s work, since her paintings explore the concept of control and purpose within a medium that often celebrates the opposite.

The curator’s talk at the preview focused unsurprisingly on the artist as individual. They discussed periods of her life as distinct chapters, referenced her mental health, her sexuality and her friendships with other artists. Many of the questions asked were about these things, they all become handy, sturdy little hooks on which to hang the work and look at it from a comfortable aspect. At one point a journalist even quibbled with their decision to have white walls as a background to the work, with the curators citing Martin’s own preference for white, as far as they knew. And all of these reasonable, if slightly absurd, lines of enquiry, seemed designed to keep the bigger question at bay: what do we make of the stuff?

At a funeral, everyone uses the weather or the convenience of the train journey to fill the time before the service, rather than addressing matters of life and death head on. It felt as though Martin had posed a particularly direct question about art, and everyone was avoiding it because it was presumed unanswerable and they were afraid of what that might mean. They were all journalists and curators after all, whose jobs are, basically, ‘to make something of things’.

And here I am doing the very same. If I left it up to you, reader, what would I do instead? Just tell you to go and see it for yourself, I guess.

Well, until you do:

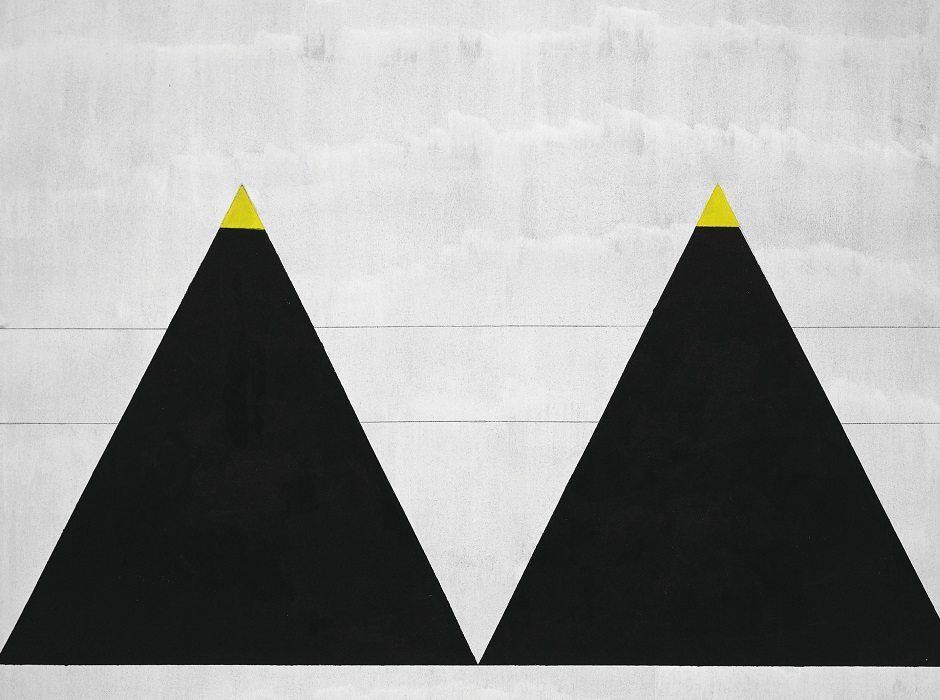

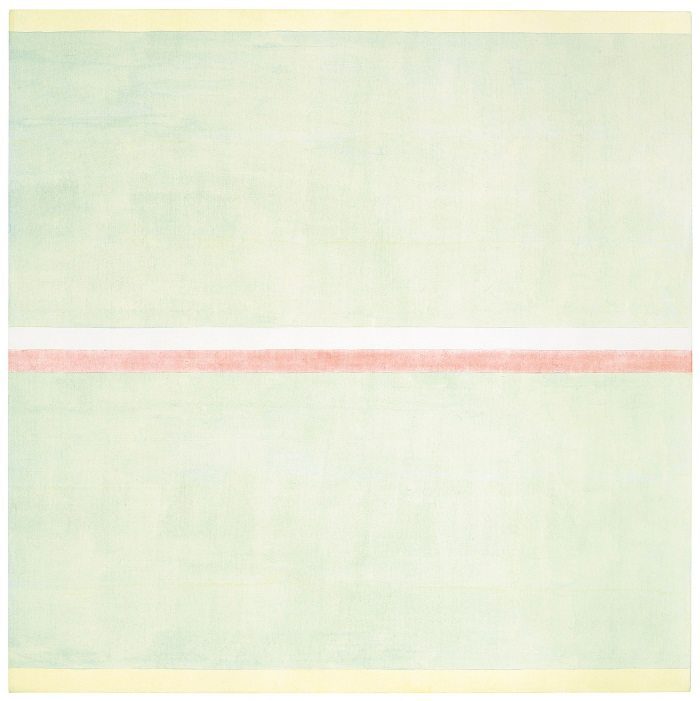

Look at this.

Then this.

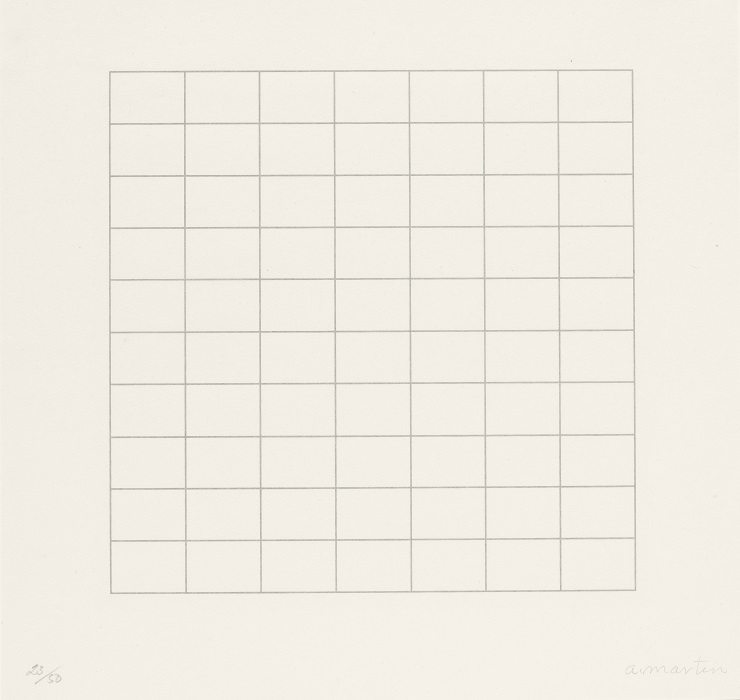

What title would you choose to give each one?

The first of the two is called ‘Gratitude’, the second ‘On a Clear Day’. Most of Martin’s work is just numbered under that familiar art-world umbrella: ‘Untitled’, which in itself serves as a statement about the indefinability of art. But a slim few were given the kind of titles that could belong to poems. I spent a while puzzling over the effect of this, as it seemed particularly important in the context of abstract expressionism, and particularly these paintings.

There was satisfaction in finding a painting had a title, since the words rooted your experience, but to withhold this sense of satisfaction, this firm knowingness, seemed to me central to the strength of the work. At her bravest, she takes the viewer beyond the terms of literature, of fiction and fact, beyond the poet’s pleasure in metaphor, beyond, even, the image, to a kind of text which can’t be defined by any analysis, since it deliberately fragments the terms upon which these systems function. Her artwork can sometimes say as little as it can possibly say whilst still existing. But what an enormous statement that is.

On the way out of the show, I almost missed a small television wired up to the sidewall. It looked like one of the TVs on wheels we had at school, which had doors on either side of the screen. Looking back these were surely there to symbolise the doors of perception, through which we watched Tintin in order to learn about the Egyptians. I sat down in front of it, and watched On a Clear Day, a film by the Swiss filmmaker Thomas Lüchinger. He films Agnes Martin in her later years in her studio in Taos, breathing heavily as she struggles to pull a big brush down a large canvas in a straight line. She works with paint that’s so thin it sloshes in a large bucket, and then has to sit down from the effort.

The physical fact of the painter seems shocking after the exhibition and its spontaneous miracles. She then is filmed sitting in a chair, wearing a shirt in the exact colour of her paintings, off-white with faded stripes of red and blue. Her voice is robust as she says, “I have no respect for human knowledge… the absurdness of facts. Philosophy was just a comparison of ideas; no revelation at all… so I gave up on human knowledge.”

It’s worth considering what it is about certain artists that make us not want to write about them. I made lots of notes on most of the work in the exhibition, but more out of a sense of duty than as an account of my honest response to it. Really, it would be missing the point to do anything but redirect you to the work itself: go and see it, and try not to control your responses to it by forming concrete opinions. Just look and think.

Although she can be said to be the artist of control, the very point of the work is that within control there is freedom. You can control the space contained within the edges of a canvas to such a finite degree that you manage to give the viewer infinite freedom to see beyond and through it to everything. The mind is the size of the canvas, and the canvas is the size of the mind. As she herself said, “From your mind there is all the help you need”.

AGNES MARTIN – Tate Modern, 3 June – 11 October 2015

Images:

1: Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

Untitled 1959

Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, USA

© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

2: Agnes Martin (1912-2004)Gratitude 2001

Private collectionPhotograph courtesy of Pace Gallery© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

3: Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

On a Clear Day 1973

Parasol Press, Ltd.

© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Headline/Featured image: Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

Untitled #1 2003 (Detail)

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Heat with our garlic. Salt to taste.

I’m not on Facebook; I’ve always resisted it’s lure. I don’t have a Twitter account on principle. I deleted my Google plus account when I started getting unsolicited material as a result of them sharing my details with third parties. I sometimes feel like the last, lonely line of defence against the supposedly emancipatory advances in communication that, I’m reassured, bring us ‘closer’ to each other and are ‘a good thing’. Because of my Luddite ways I can’t read any of your articles in full. I would very much like to read them. Is there another way? Otherwise, you see, I’m socially and culturally excluded from participating in your site and my choices have made me even more of a marginalised oddity than I already am. But I’m sure you good people at Trebuchet are very fond of marginalised oddities and, indeed, probably thrive upon exploring different perspectives. And so I’m sure you can come up with a solution. xx