During lockdown, British-Barbadian artist Alberta Whittle created a film in response to the anxieties and uncertainties of the global pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement and the ongoing climate emergency. Made in collaboration with writers, performers, fellow artists and musicians, the piece expresses a powerful sense of longing and loss as well as gesturing towards the interconnectedness of humanity

Here, Millie Walton speaks to the artist about making the film, searching for a sense of reprieve and inviting the audience to engage more actively.

When was the idea for RESET born and how did you go about making the film?

When lockdown began, I thought everything would slow down for me, but instead, I felt the world unravelling. It was almost like a vortex that we fell into. I found myself so personally affected by everything that was going on.

I ended up going back to Barbados to be with my family during lockdown and I started thinking about what family means, but also what community means more generally, especially when you’re trying to offer care and support to loved ones and friends from a distance. I developed such a longing for the people in Scotland, South Africa and the US that had become my family. We were having conversations about grief and loss, but also about the huge inequality of the pandemic and how there’s no going back, how there’s no such thing as “normal” anymore. So, the film was really born from those conversations and then I was given the opportunity to make it through the Frieze Artist Award, which allowed me to bring together friends who work in performance, photography, writing and costume design. So many people brought their wisdom and research to this project.

I really didn’t anticipate that I wouldn’t be able to get back, but Barbados kept its borders closed for most of 2020, which meant that even the filming of the sequence with Mele Broomes, who’s the dancer, had to be directed entirely over WhatsApp.

What was it like for you working in that way?

At first, I felt a bit frustrated because I really desperately wanted to be there and there’s so much about longing in the text that Ama Josephine Budge wrote for me as she’s reflecting on touch and moments of intimacy. However, when I realised that I wasn’t going to be physically in Scotland, I started to get quite excited because the project became a gesture of hope. Trust was very important, and while it was sometimes tested, it also flourished.

Do you think the experience has made you think differently about how you make art?

Definitely. I also ended up making a remix of my film Business as Usual and again, I wasn’t able to be there physically but in that case, it was because of a natural disaster: a volcano struck Saint Vincent and we were covered in ash.

I tend to work with the same network of friends and family, which grows as more people come in, but when you’ve been working with people for a while, you develop this wonderful kind of short-hand in terms of language but also expectations. People get to know what’s crucial to a project and they start bringing in their own ideas too, which I really appreciate.

RESET is filmed across Scotland, South Africa and Barbados – do those locations have a particular significance to the narrative that you’re telling?

Absolutely. Growing up in the eighties, apartheid was constantly on the news and being discussed in my household so South Africa is a really important place in terms of my own education. I also think that South Africa teaches the world so much about what social justice looks like but also shows how deeply oppression is undermining so many of the racial infrastructures that we live in. And Barbados is a place that I think directly speaks to the UK in terms of its history, even though that’s largely ignored. I’m interested in bringing these places together that are special to me and showing the relationships that they have.

The sea or images of water also feature heavily in the film. Does the sea hold a particular significance, or symbolism for you?

John Akomfrah speaks about the sea as history and that’s an idea that really resonates with me. The sea is a site of arrival as well as departure. It’s impossible for me to ignore the histories of empire and imperialism that would have defined these landscapes and scarred them. So, when I return to water, it is about trying to hear those thoughts, about acknowledging the scars but also trying to heal them.

How did the title RESET come about?

The title was originally much longer, but I really liked the sound of the word “reset”. I read this beautiful text about phantom limbs and trauma. A phantom limb obviously suggests that something is missing, some kind of violent action has severed a body part, and in the text, the writer put forward this idea that in wake of colonialism, we’re all phantom limbs. He also wrote about how one of the ways to heal that severing and find a reprieve is through sound. I think the idea of resetting is about looking for that reprieve: resetting our ideals or resetting the body so that it can look at what has been severed from it. At the beginning of the pandemic, I was thinking so much about anticipatory grief, but by the time I was making RESET we were already within that grief. So, how do we find reprieve? How do we start to build some kind of recovery?

How much do you think about your audience when you’re making the work?

All the time. It’s like they’re sitting on my shoulder. When I grew up in Barbados, we used to go to the drive-in a lot and it’s a place where audiences are incredibly expressive. Everyone is shouting at the screen, sharing a kind of critique or telling the hero or heroine what to do. It’s very reciprocal, and I really enjoy that. So, with my own work, I almost want the audience to be able to engage in a vocal way.

At the beginning of RESET, I lead a meditation, which is also about exhaustion, because it was such a long, tumultuous and unsettling time for so many of us, and I want the audience to be able to just sit and prepare themselves to enter into the film. What I’m talking about is, in some ways, quite distinct from conversations about equity or race because within those conversations, I also want there to be self-compassion and a moment where we actually acknowledge each other’s humanity and the deep relationships we have to each other. I think often when people witness films – and I use the word “witness” very specifically – where race or gender or class is touched upon, there’s this sense that it has nothing to do with them, and I really want the audience to understand that they’re actually implicated in these histories, in these stories.

Now that audiences are watching things more remotely, I found myself focusing on how the body is prepared before it starts taking in the information that’s in the film and also, thinking about what state of mind people might be in when they come to see it. If a person is watching it online, for example, there might be a child wanting their dinner in the background. Where possible, I want to be generous to the audience.

What drew you to start working with film?

I’ve always loved cameras. I love the feeling a camera has in my hand and I like the agency of it, but if I’m honest, it was only really when I felt like the political situation was getting out of hand that film felt like the natural way to respond. I made my first film when the student movement was happening in South Africa and I was deeply disturbed by how the students were being treated, but I also felt as though these conversations around history and race were becoming also like clickbait. The film is quite satirical, but it was a way for me to speak in a very clear way. I also edit quite quickly, which means a film is something I can make and get out in the world fairly rapidly. Like I said at the beginning of our conversation, I thought 2020 would be a quiet time, but the world was on fire and I felt I wanted to be part of that moment through making work. I ended up making three films in 2020, which thinking about it now, seems insane.

How do you think your video works fit into your wider practice?

I work with collage a lot, and the way in which I make my films is by using those same methods, but films have become a kind of anchor for me. I think I trust myself more with my films. RESET was an opportunity for me to produce an installation and sculpture works around the film, which highlight particular ideas or perhaps, set the scene in a particular way.

I’m very interested in the energies of spaces and how we can absorb them. Jupiter Artland, for example, is a space where I find myself getting very creative. I had already made some work before arriving, but ended up making quite a lot more when I was there and I had the film playing continuously in the space.

Can you reveal anything about the work you’re making for the Venice Biennale?

Oh, I wish I could, but I have been sworn to absolute secrecy.

“RESET: Alberta Whittle” runs until 31 October 2021 at Jupiter Artland. For more information, visit: jupiterartland.org

Alberta Whittle will represent Scotland at the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale in 2022.

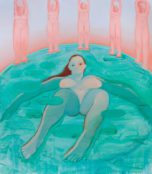

Featured Image: Still from Alberta Whittle’s RESET, 2020. Image courtesy of Alberta Whittle.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.