[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]otion cut to emphasise time, tunnels of meaning and exploratory symbolism.

Alex May uses digital photography and associated media to capture and present a view of the natural world that suggests the concept of hyper-photorealism: photography is adapted using digital techniques to show life in movement, capturing actions, reactions, interactions and avoidances. An overriding topic in Alex May’s work is the idea of flow and context which he often underpins with a baseline of physical motion. Objects are defined by their interactions however they paradoxically remain themselves throughout, a process humans in general barely notice but one which we become more aware of when we consider machines of recognition and learning, the key for anything to function in a world of variables.

Consider 15 minutes of a pigeon’s life in an Italian square. At one time it is sitting on a statue’s head, then walking towards a crust on the pavement, pecking the crust, fighting with a colleague and then wheeling about in the air where it avoids the statue to get to perch in an ancient portico. In each context the bird is conceivably a different class of interactive being (flying object; consuming animal; environmental decay; statue cliché; etc.) with a variety of implied potentials distinct from each other and easily dislocated from the other states.

If a human looked up from their newspaper at 20-second intervals they might not know that it was the same bird and read each vignette as a distinct event of greater or lesser importance based on proximity and context. May’s work draws all those concurrent events together into a single image and thereby gives a more complete picture of his subject as a multi-class entity. This is taken forward dispassionately where novel and repetitive actions appear equally in the frame captured only as differences in time and space.

Receiving a high-profile commission in 2017 for the Francis Crick Institute Alex May again investigated movement, repetition, context and photographic image however the play here was with threads of activity rather than solo subjects. In Flow State he worked for 18 months to create a symbolic experience for visitors of an institute with over 1,200 scientists, a number of different groups, organisations and programmes. Going live on July 12, 2018, Flow State explored the interplay of visitors and concepts even before people had entered the turnstiles of the building itself.

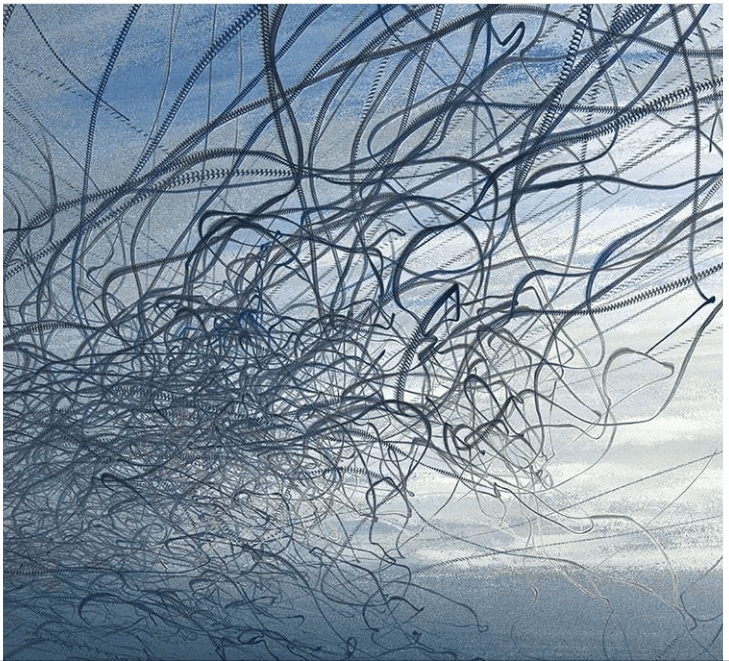

Alex May, Untitled, 2018.

Alex May: Investigation as spatial analogy

People can go into the foyer and there’s a big gallery off to the right which they have regular exhibitions in, but beyond the turnstiles, you can’t see much of what lies beyond… a flow of information and connectivity. Because the way science is often presented to the public, it can be this fairly impersonal thing; you hear about the top-level people who are at the top of papers, but you don’t get to see the thousands who are doing the pipetting every day, or the endless experimentation and number crunching. Those that do the repetitive work report they get into a flow state, which is something I also experience when I’m programming, so I wanted to reference that in the work and the title. These people are as much part of these breakthroughs in the long-term as anyone.

I had this amazing unprecedented access to the building, and many scientists, who were very generous with their time. Some of them asked me, “Are you going to be explaining our work?” I told them there’s no way I could meaningfully take somebody’s complex research and—without any text or voice—convey a deep understanding to somebody on the other side of the glass. This was never the aim of the artwork anyway: it was more about taking visual elements of that research and processes and creating compositions and aesthetic experiences that would intrigue people and guide them to latch on to things that look familiar, to draw them in.

In the main video there’s scenes that look like landscapes or flowers or lightning in the sky, but it’s actually all layers of scientific imagery. It’s trying to create a curiosity about it, because much of science is curiosity, that’s what drives it all; these are very curious people who are doing this work to understand the world. That’s the common message that I want to get across. […] All along my goal was to create a work of art and not a piece of science communication, and they were always fully on board with that. […] In my experience there is a growing enthusiasm for scientists working with artists, and vice versa because it can be a real win-win relationship.

This project was somewhat unique, in my experience, in that I was an artist engaging with an entire institute, rather than an individual lab, researcher, or subject. I had to find a way to get a meaningful overview of this vast place. I started with an aesthetic exploration of the building, as I was given such free access. I’d be filming the roof and the ductworks and networking wires along the corridors.

They were asking, “What are you filming that for?” It’s great; it’s like the nerves that drive the science. It’s amazing to see the scale of infrastructure in that building.

It was definitely a strong aesthetic journey. I spoke to many scientists, one of whom was obviously a little unsure why he had to speak to me and said he only had 20 minutes. Our conversation was uneasy and faltering until he mentioned using fast Fourier transforms, which I’ve used a lot in my art projects in the past for audio and image analysis. When I revealed my understanding of them, he visibly relaxed and we got on brilliantly after that—he spent two hours showing me his lab and introducing me to his colleagues, and they generated me exactly the footage I asked them for. I’d also make a point of speaking to the cleaners and the security guys in the loading dock, and the people running the infrastructure—I wanted a holistic impression of the entire place.

As the project developed it became clear that it was these three strands: there’s the science itself, there’s the people, and there’s the building. It’s like a body, with its veins and nerves facilitating the science that’s going on there. All these different labs might need different gases pumped in or very pure water; all this stuff has to be delivered safely and controlled.

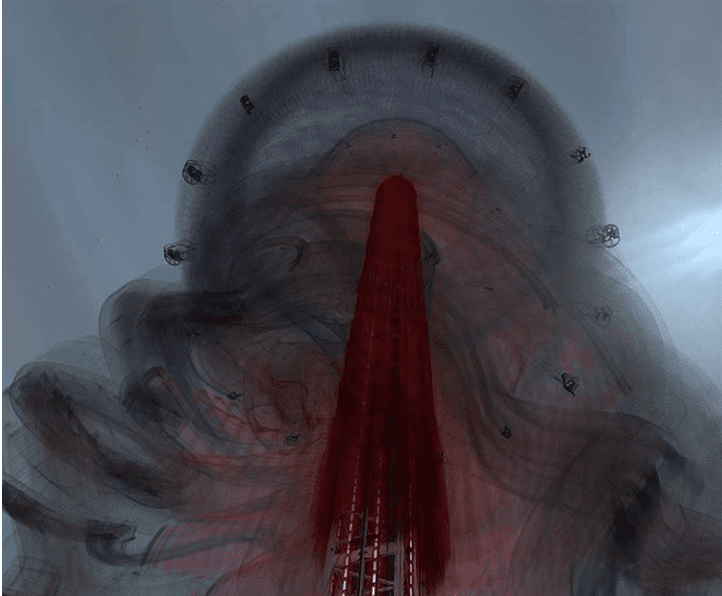

So it was very much about presenting the three strands. That’s why I was so keen to keep a human element in the story and to reflect on this incredible building driving it all. It was a way of anchoring and embodying even the most theoretical of science into a physical form. The shape of the sculpture is based on an epigenetic diagram, that reinforces the process of revealing layers and layers of information.

Alex May, Untitled, 2018. 4

There’s an interactive element to the work: if you stand back from it—it had to work on different physical distances—people walking by the building will see a single video piece that’s played across all of the monitors. There’s 28 screens in total. You see this one video artwork, that is entirely comprised of layers of scientific imagery. As you get closer, there’s a camera that picks up the fact that you’re there, and it starts to change the screens to show the building footage and more artworks and the people working.

The idea is very simple: the closer you look, the more is revealed. They’ve got so many amazing machines there, these massive microscopes of all different kinds, and the closer you look, the more data is revealed, so I wanted to embed that: the closer you get to the building, the more information you’re presented with. You see lots of hands of people working and see what they do on a day-to-day basis. It’s this balance between this organic, natural trying to understand the mechanics of biology and the world, and the rigidity and structure of the building that was made to house all this.

I can see it directly fulfils one of the key aspects of the project, which was to get people to come into the building, and to help people pass that initial stage of being intimidated. I found the building very intimidating when I started going there. I’ve never really felt that before. So I think it helps; you’re focused on looking at the artwork and by the time you’re up close, you can see the people behind sitting in reception and that it’s alright to go in.”

Alex May continue in print. Read more in Trebuchet 6 – Time and Space

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle