[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]H[/dropcap]edley Roberts’ ‘non-portraits’, as the artist has referred to them, present a challenge to the viewer; they are after all of something.

That ‘thing’ is generally figured as a person, either in the outline or in the title. The picture plane cropped close to the head often includes combinations of features such as eyes, mouths and some other basic paraphernalia; hats, glasses, hair-coverings or beards. There is an identity implied by these features, and a clear effect (akin to encountering stranger) in looking at the work where the glare of the strange ‘thing’ confronts or eschews the viewer’s own gaze.

With this in mind, in what sense are they ‘non’? In terms of the symbolic and narrative possibilities this effect of being confronted with a fetishisticly loaded shape (the head) and the central question above represent the hook or crux of the work. The viewer is asked to consider accustomed form as alien; the usually reassuring familiarity of the face is made to speak of the ambiguity of the person behind the fleshy mask. The otherness which a gaze can convey on another person (such as the objectifying male gaze or, indeed, that of the artist and his subject) seems at odds with the otherness apparent in the subject themselves. Two forms of dehumanisation, the one reductive and the other expansive are clashing over and over again. This oscillation works because the figure or person is simultaneously there and absent. Their presence is an interrupting void sucking in projections and generating ever greater ambiguity. Or the blacked out interior of the figure could represent what is left after the excoriating vision of other people is done with them.

This interplay of forces from without and within is supported by the different levels to which the personages depicted are figured or obliterated. We can identify three distinct categories: those which contain the most features, such as: Big Marina (2018), Art Student (2015) or Cowboy (2017) are also the least threatening. Those works have a positive air; the faces are more pronounced, offering some tonal undulations, the colours employ a high contrast and the expressions in the eyes and mouths are non-aggressive, while the paint is not so tortured via process.

This way of seeing the work is one option, since there are knowable and interpretable images within it; links we can draw to make sense of the artist’s language. However, the works are all very much process-driven, painterly, and concerned with surface, colour and viscosity. The more formal aspects are so prominent: history of the painting, visible marks, fast application. It would be neglectful not to address these, since it may be that all the pyscho-interpretation is no more than a secondary concern to a painter obsessed with painting. Colour vibrates against colour, brush strokes carry the eye around the surface, butting up against one another. The approach, even in relatively sensitive images such as Story of O (2015) is one of attack: no careful hesitations. Instead, it’s fast work, layering and editing. Big Marina (2018) is an excellent example of the method; the red outline isn’t drawn around the head and hair, the remaining slither sings out between the deep blue, black and pale flesh colours. The ridges of brush strokes reference time and energy. These qualities make even the more disturbing images pleasurable to look at.

‘Any painting is a self-portrait’. To what extent is that true, and what does this say about portraiture?

For me, painting is a way of being in the world. It’s a method by which someone who calls themselves an artist tries to reconcile the inevitable existential difficulties of negotiating the experience of being. The work that an artist makes is a bridge from their world into the world of others. We can try to have empathy with others, but we can’t experience their world, and so the artwork is always a view from the perspective of the artist, whether it’s a portrait or not. So in that sense, all artworks are portraits of the artists’ world view.

What is the relationship between the subject and the painter?

The subject of an artwork isn’t always the same as the content. For example, in a painting of an empty chair the subject could be the idea of ‘absence’. However, in portrait painting, there’s a fundamental idea that the painting captures some inner aspect of the sitter who is portrayed.…[Read more]

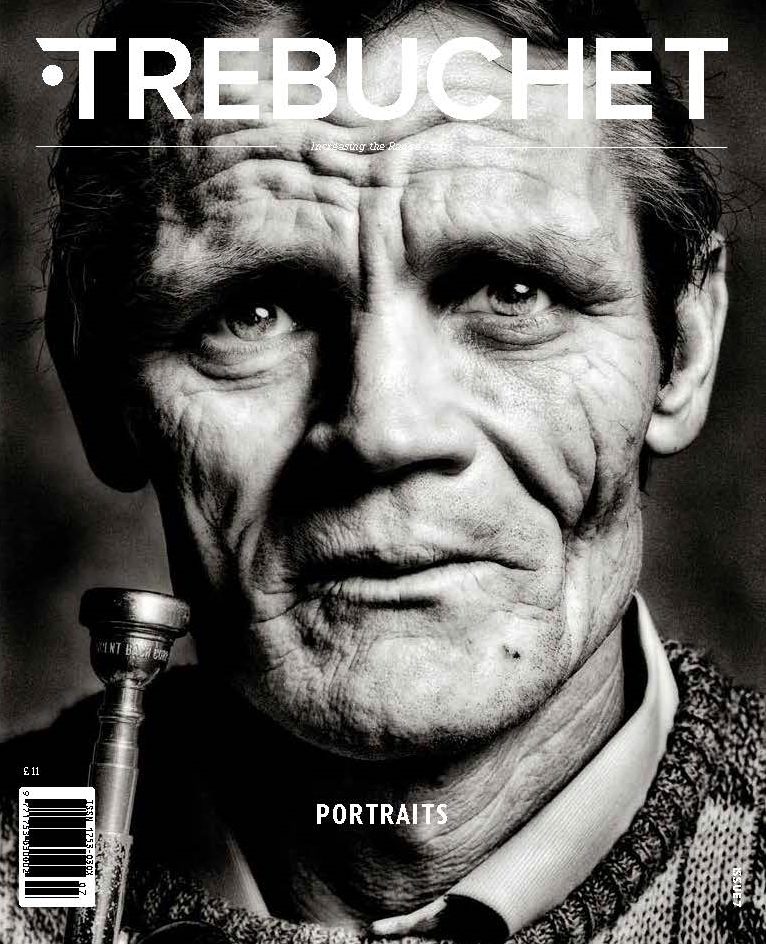

Read the full article in Trebuchet 7: Portraits

Michael Eden is a visual artist, researcher and writer at the University of Arts London exploring relationships between monstrosity, subjectivity and landscape representation.