[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]F[/dropcap]amily and friends mourn the death of David Robert Jones, bereaved by the loss of the man they ate, drank, laughed, played and argued with. Our condolences and sympathy go to them.

For those of us who knew him as David Bowie, the loss is less personal, but is nonetheless poignant. It is ever the case with the death of a public figure that a confusion of emotion fuddles the rational and emotional parts of the psyche. Feeling bereaved at the death of a remote figure seems indulgent, an imbalance of sympathies which could more fruitfully be directed to those with greater need. It is the post-Bataclan argument (in which those moved to superimpose a French tricolore onto their social media profile pictures were derided as guilty of disproportionate response to a remote event) twisted to fit a false paradigm in which feelings of sadness or loss are somehow finite, to be hoarded for appropriate moments, and distributed in accordance to need.

Regardless, and acknowledging the fact that in the age of social media attention-seeking every action or expressed emotion will have its detractors, the death of David Bowie is a communally-felt loss affecting hardcore fans of his work and casual admirers alike.

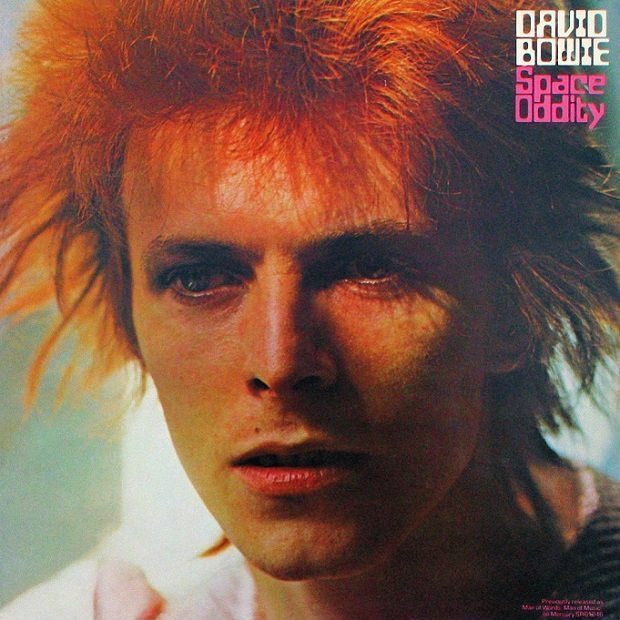

As a reflection, or perhaps a director, of human culture, Bowie drew from the symbols and semiotics of myth, contemporising archetypes which have been crucial to humanity’s concept of itself since time unrecorded.

Giambattista Vico’s reduction of all time to the Age of Gods, the Age of Heroes and the Age of Men finds its expression in the personae invoked by Bowie’s chameleonic periods. Star Man, Thin White Duke, Major Tom. On one level: little more than marketing tactics to advance a long-term musical career; on another level: the unconscious expression of a collective imagination endorsing symbols and narratives at the centre of the human condition.

It is the loss of Bowie as interpreter of these archetypes which prompts the quite real grief felt by millions, the majority of whom had no personal contact with the man. Artists channel the memories and hopes of the species in expressions which lack the rational detail of science or history, but which resonate with a meaning which is older and more universal than either.

Projecting such importance onto David Robert Jones is inappropriate – our expressions of sympathy with his family can be no more than that. That notwithstanding, a sense of sorrow at the loss of so pervasive an interpreter of human narrative as his David Bowie persona, is to be expected. Where politicians, social media celebrities, Kardashians, athletes, engineers and architects add to the noise which pervades communication, artists such as Bowie embody the myths which are central (via film, song, photograph, etc).

All versions of myth are worthy of consideration, regardless of the guise they take. Every message, be it linguistic, figurative, metaphoric or musical, is transmitted through a medium. Every medium distorts the message, adds noise, and leaves the receiver with a mixture of noise and message. If a message is sent in multiple ways, the receiver can compare received messages in some imaginary space of mind, see the common structure, and sift out the noise.

An example, of many: Nicholas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth cast Bowie as an alien on Earth, searching for a way to transport water to his wife and child on their home planet. Translating the myth of the Fall to celluloid, Bowie’s alien dons skin (thus echoing the energy-to-matter transmutation of Genesis as well as the consequent separation from the feminine twin – a dichotomy of male will/feminine imagination – central to Gnostic mythology), attempts to achieve his goal, but ends up trapped by the terrestrial social and economic concerns of base humanity.

God, hero and man in a single film, Bowie’s character descends into alcoholism, the irony of his addiction to a corrupted ‘water of life’ made clear through the film’s cinematic and musical techniques.

It is clear that we are expected, as viewers, to draw allegorical conclusions from the work, particularly with regard to the excesses of capitalism, but the film’s adherence to tropes of mythic symbolism set it apart from standard cautionary tales. Bowie’s role as an otherworldly presence set the tone for his artistic personae throughout his career, whether consciously on his part or as projected transfiguration by his audience.

Wikipedia will provide details and discographies. Iconoclasts will quibble at the suggestion of mythic import (and ask disingenouously whether his Tina Turner barnet in Labyrinth is an emanation of the Mother-Goddess), feeling threatened by high-falutin’ concept and taking solace from the reassuring chaff of times, dates and chart positions (coupled with the emotional disconnect of sarcasm). None of which, even when combined with the narcotic warmth of nostalgia evinced by the oncoming heavy rotation of his hit singles, explain why Bowie’s death should be felt so keenly by so many.

‘He sang of space and drugs and floating above the world. He could be so tender… and then swagger like a brute. He was tapped right into something mystical that we recognised but could not grasp as we were too busy preening and dancing and wanting.’

– Suzanne Moore, The Guardian.

As artist-interlocutor, conduit of culture, and embodiment of the structures by which we make sense of our world, David Bowie excelled. His oeuvre enjoyed popular acclaim on many occasions, languished in obscurity on others. At all times, it carried the status of exotic Other.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.

It’s strange how one can feel a sense of loss over someone they’ve never actually known or met….but when those people represent a certain part of one’s life at some point or other it’s like losing an old friend I suppose. Perhaps then it’s not so strange after all. Actually dreamt about him last night as well. Lucky me. Sleep well Starman. x