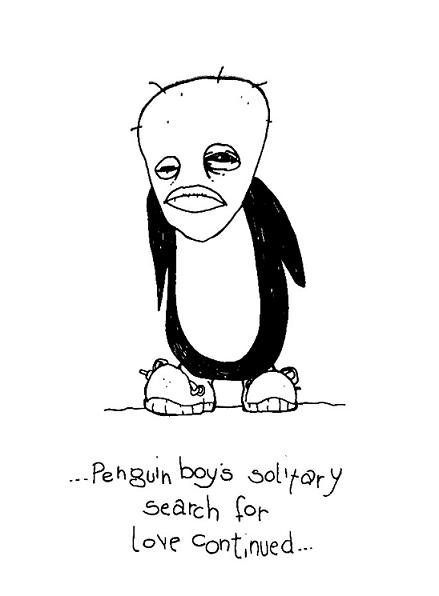

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]hy animals compare the present with the past.

Animal cognition: sad, happy, horny, bored. It all becomes the same penguin in a black and white world.

According to standard theory, the best response to current circumstances should be unaffected by what has happened in the past. But the Bristol study, published in the leading journal Science, shows that in a changing, unpredictable world it is important to be sensitive to past conditions.

The research team, led by Professor John McNamara in Bristol’s School of Mathematics, built a mathematical model to understand how animals should behave when they are uncertain about the pattern of environmental change. They found that when animals are used to rich conditions but then conditions suddenly worsen, they should work less hard than animals exposed to poor conditions all along.

The predictions from the model closely match findings from classic laboratory experiments in the 1940s, in which rats were trained to run along a passage to gain food rewards. The rats ran more slowly for small amounts of food if they were used to getting large amounts of food, compared to control rats that were always rewarded with the smaller amount.

This so-called ‘contrast effect’ has also been reported in bees, starlings and a variety of mammals including newborn children, but until now it lacked a convincing explanation.

Dr Tim Fawcett, a research fellow in Bristol’s School of Biological Sciences and a co-author on the study, said: “The effects in our model are driven by uncertainty. In changing environments, conditions experienced in the past can be a valuable indicator of how things will be in the future.”

This, in turn, affects how animals should respond to their current situation. “An animal that is used to rich conditions thinks that the world is generally a good place,” Dr Fawcett explained. “So when conditions suddenly turn bad, it interprets this as a temporary ‘blip’ and hunkers down, expecting that rich conditions will return soon. In contrast, an animal used to poor conditions expects those conditions to persist, and so cannot afford to rest.”

The model also predicts the reverse effect, in which animals work harder for food when conditions suddenly improve, compared to animals experiencing rich conditions all along. This too has been found in laboratory experiments on a range of animals.

The Bristol study highlights unpredictable environmental fluctuations as an important evolutionary force. “Rapid changes favour individuals that are responsive and able to adjust their behaviour in the light of past experience,” said Dr Fawcett. “The natural world is a dynamic and unpredictable place, but evolutionary models often neglect this. Our work suggests that models of more complex environments are important for understanding behaviour.”

Illustration by Dan Booth

Source: Eurekalert. University of Bristol

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.