[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]orks by the seminal British painter John Hoyland (1934-2011) are currently on display at Tate Britain curated by Andrew Wilson. Following Naila Scargill’s article, Seminal John Hoyland Works to Be Part of Tate Britain Spotlights we thought it would be good idea to expand further on Hoyland; drawing on an influential 1978 interview with Adrian Searle, Hoyland’s appearance in the BBC documentary Six Days in September and his place amongst his peers and critics.

Outside exhibition going circles Hoyland’s practice has been brought to the broader public in the BBC archive documentary Six Days in September first transmitted in 1979 as a part of the Arena series, and currently available to watch. The artists unpretentious attitude, bold editing and overall skill are displayed alongside his asides regarding painting and art.

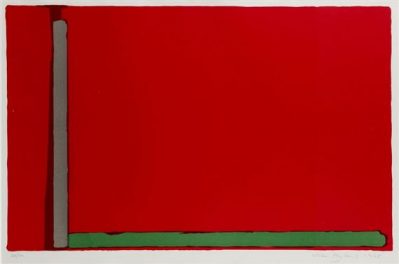

‘The eye basks in front of Hoyland’s wide fields of glowing red and green like a cat before a fire, immersed in sensuous pleasure.’ Robert Hughes

One Such aside laments the stereotype that the act of painting is relaxing or therapeutic; for Hoyland painting is a difficult process fought out stroke by stroke, and the end result is evidence of that exchange with the canvas. He works large, starts abruptly and begins to apply paint gradually decisions become more considered and his narration express his humour but also betray his growing frustration and ambivalence toward the finished work.

Painting, real painting may not be therapeutic but watching Hoyland in this gem of a documentary is, especially for budding creatives so desperate to avoid cliche’s that they critique themselves out of the creative act altogether. Hoyland begins and then undertakes the process of moulding his activity into artwork, not expecting a victory and struggling with his own doubts he ploughs ahead adding and subtracting.

Here we look at some selected passages from an interview with Hoyland who worked successfully through the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s and into the 2000’s we don’t get a sense of the fool who believes their own myth here. What we get is a consciousness negotiating with a medium and with reality, consider the references to process below,

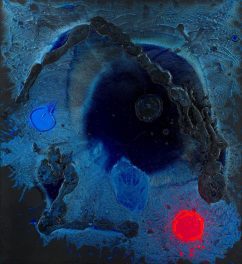

Detail from ‘Longspeak’ (1979) by John Hoyland

‘JH: I use the process, but only when it works for me, I’ll add to it, or adapt it. In this painting here… I don’t know which bits came naturally, some did and some didn’t. These notes of colour serve as a way of directing the eye, or of holding the surface together, holding the painting in check. When they become decorative embellishments they don’t work – they’re over the top – but they are like subsidiary characters.’ Hoyland in Searle (1978)

When Time Began (Mysteries II) 15.11.10 2010 John Hoyland

Tactical Combat

As above in the section below we get a sense of these negotiations as attempts and then revisions, successes and failures mediated in the present by a mind in the act. This has been referred to as a kind of boxing match or act of endurance by Sean Scully (a fellow painter) “Boxing requires a huge amount of intuition,” he says. “You have to change your mind about what you’re doing, while you’re doing it. That’s intuition. That’s a lot like what I do.” (Scully in Karlsruhe, 2018) Scully is emphasising the problematic nature of being confronted so directly with ones own output. The process is a battle ‘combat’ not an out pouring, but a conversation or debate with your decisions.

Scully’s attitude is in part a rejection of the ‘nature boy’ or ‘wild man’ of art myth so often a projection of the outsider, ‘he notes (Scully) that a boxer can’t just “go in there swinging”. Neither can a painter, but it is more common for a boxer to compare himself to an artist than the other way round.'(Karlsruhe, 2018). Hoyland also highlights, strategy and battle, the mental strain of the creative endeavour,

‘JH: it’s another way of backing into drawing – because if I draw directly with a brush I tend to get self-conscious about it. If you press it on it’s one stage removed from the hand and wrist, it allows the process to intervene in the making of the shape. If it doesn’t come out right you just scrape it off and do it again till you get something you identify with. The paint is usually scraped, pressed or dripped. I don’t use a brush much in the finishing of a painting. I can draw with a knife in a way I can’t with a brush.’ Hoyland in Searle (1978)

‘He’s like a vicar who wants to meet real people, wants to get down and boogie with the workers’ Hoyland 1978

Again below we have Hoyland describe a conversation he is having with himself and the work of another artist; the authorial voice so derided by Hal Foster which we see in Natalie Andrews investigation into ‘the Expressive Fallacy’ seems here a far more humble thing, decision after decision a dialogue with both other painting and ones own sense of composition.

‘AS: He was trying to challenge that whole reductive thing… I see some links with Larry Poons in your work – in the thick, trailing drips…

Larry Poons, Untitled, 1980-1981

JH: Maybe I’ve been an influence on him or vice versa. I’ve always felt that his work had limitations and in a way my work is a criticism of his. My work is a criticism of itself, I think one’s work is a criticism or a challenge to other painting.

AS: Motherwell said something about painting being at once a homage and a criticism.

JH: That’s very true.’ Hoyland in Searle (1978)

Elegy to the Spanish Republic, No. 126, by Robert Motherwell.

Potency and Practice

Tellingly below we see the power reversal which Hoyland and Searle address but which is often absent today where pundits have become increasingly important; Hoyland’s challenge seems to reinforce that creativity is a more difficult but less frustrated activity that that of the critic, in who he sees a kind of bitter self importance. And perhaps more depressingly a creative impotence.

The critic Robert Hughes reflected that, ‘the vibration which Hoyland sets up between an orange bar and its green field is dazzling: colours float, disembodied, off one another, but their apparent position in space is contradicted by a smoky dark edge of washed paint that pulls them back again, turning a veil of pigment into a solid object’ (Robert Hughes 1967). Having highlighted his nuance Hughes goes on to emphasise the sheer impact and affect of the works seen in person. This embodied experience of both the painter and the viewer is where the potency of Hoyland’s practice rests.

Human Nature, 1996, Sean Scully.

The Role of the Critic?

Hoyland categorises critics as poets via analogy or deluded both though who comment only on art, his attitude is tonic in a world obsessed with chattering discourse and calls to action. What Hoyland does is remind us that we should also attend to our own perception be that as viewer or artist and his withering comments about trendy vicars (below) should be taken seriously after all, and by way of a contemporary example Goldsmiths fine art school is currently run, not by a practitioner but an art critic Michael Archer, how times have changed.

‘AS: What do you see as the critic’s role?

JH: To interpret to a wider audience what the artist is doing. In very exceptional cases you get a critic who is like a poet – and who makes some analogous, equal contribution to what the artist does, but only by analogy. But the critics can’t tell the artist what he should be doing. Richard Cork talks about being an intervener – to intervene. I don’t think he can handle it. He’s like a vicar who wants to meet real people, wants to get down and boogie with the workers.

AS: I think the art should always come first in the relationship – the art precedes the criticism. It’s up to the critic to meet the demands of the art, and not the other way around. Critics who want art to mediate between some general social context and their own hang-ups should shut up and do it themselves.’ Hoyland in Searle (1978)

‘What we need more of is slow art: art that holds time as a vase holds water: art that grows out of modes of perception and making whose skill and doggedness make you think and feel’ Robert Hughes

It was once commented in relation to the American dominance in the area of abstract expressionism that if Hoyland didn’t exist it would be necessary to invent him, now that Hoyland has passed we can only hope that new generations of artists will reinvent his terms, utilise some of his legacy and make it their own, resurrecting as it were some of his potency and impact.

Large Swiss Red, 1968 John Hoyland

Anti-sensational, Slow Art

The artists referred to here Hoyland, Scully, Motherwell and Poons seem to be part of another world; their work is not frivolous or fun, and its also not overtly politicised furthering in a literal way some cause or contemporary issue which however right on, always seems to alienate most people. The art critic Robert Hughes in address at the Royal Academy stated,

‘What we need more of is slow art: art that holds time as a vase holds water: art that grows out of modes of perception and making whose skill and doggedness make you think and feel; art that isn’t merely sensational, that doesn’t get its message across in ten seconds, that isn’t falsely iconic, that hooks onto something deep-running in our natures. In a word, art that is the very opposite of mass media.’ Robert Hughes 2004

This seems to be the power of such practices that they can offer something other to mass media and its faux urgency, something which is grounding, and spiritual; this is why we should go and see Hoyland’s work while we can.

References

Hughes, R. (2004) From the address by the art critic to the Annual Dinner of the Royal Academy of Arts, in London.retrieved at: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/commentators/robert-hughes-we-are-losing-the-skills-on-which-true-art-is-built-41705.html

Hughes, R . (1967) ‘Art: How colour really works’ by Robert Hughes. The Observer. retrieved at: http://www.johnhoyland.com/art-how-colour-really-works-by-robert-hughes/

Searle, A. (1978) John Hoyland’ interviewed by Adrian Searle. Accessed at: http://www.johnhoyland.com/spotlight-on-the-archive/ (27/12/18)

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.