[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap]rboretum: The art of trees, the Arborealists and other artists.

Shakespeare often used murky forests and prickly undergrowth in his plays as spaces where carnival and otherworldly events could be performed. These woods are liminal places, on the edge of civilisation, creative centres of critique.

Similar to many of the Bard’s characters that take a trip to these woods, the viewer of this RWA exhibition is thrown into a magical world of organic transformation and thought-provoking negotiation. A bold sculpture comprised of several steel and bone white sycamores clearly sets the woodland scene. Its confidence and orderly appearance invites us in. Yet it is also quietly subversive by defying the conventional space of the art gallery and taking the inside outside. Its almost as if we can hear the crunch of leaves underfoot as we walk towards this sculpture, so powerful is its provocation of being a ‘real’ forest.

This reminds us that trees, like all organic life, resist containment and frames. Fittingly, many of the paintings also included in this show are left raw and unframed, exposed to the elements – and artistic scrutiny.

There is a curious mixture of styles, from the highly naturalistic, to the hyper-realistic, to those flirting with abstraction and those that are fully immersed within it. This conveys a clear sense of experimentation and exploration into which styles are suitable for contemporary portrayals of a long-examined subject.

Fiona Hingston’s piece called ‘Findings’ displays found natural objects from the floors of Biddlecomb Wood in the style of a Modernist grid. This rings strange with the natural materials and subject matter, making us question how we make sense of our surroundings.

Even more curious is the concentration on the materials and texture of trees rather than on their subject matter per se, even though the exhibition information stresses the art historical importance of the subject matter.

Anthony Whishaw’s highly abstract triptych ‘Coppice III’, 2000-1, incorporates sawdust into its thick, earthy paint, concentrating on the texture and abstracted individual leaves within a canopy. This painting is about patterns in nature, the oddity of nature’s repetition and the artistic satisfaction of when this goes awry.

Whishaw’s work is not alone in this view. Instead the majority of the artworks on display suggest that the picturesque is created by abnormalities and intriguing differences. Trees are not idolised (and certainly not in the ways that they have been throughout art history) but are shown as fragile and vulnerable beings in need of care and protection. We could go so far as to say that materiality is emphasised as a way to break down myths about trees and awaken us to pressing ecological issues. Indeed, our desperate, complex and even hypocritical relationship with them is revealed. This is pertinent because the opening of this exhibition was the first Green event to be held in Bristol during its year as European Green Capital.

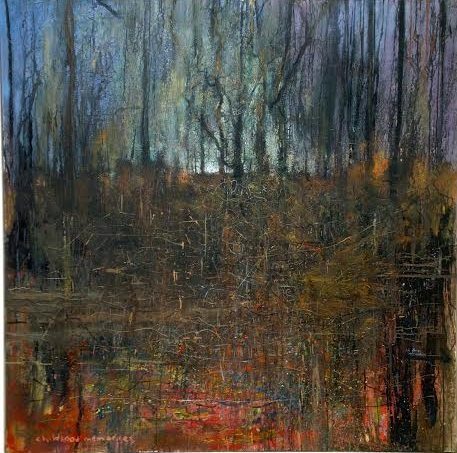

Despite this ecological turn, and emphasis on our precarious and precious relationship with trees, there is a distinct absence of people in the artworks. These are lonely woods. Are they lost, forgotten, abandoned? However, one can argue that in place of people we are given people’s memories. For instance, Kurt Jackson’s deeply atmospheric oil painting is entitled, ‘Childhood Memories’. The chunky slashes of paint convey a sense of hazy or unreliable memory; it is murky with muddy thoughts that the forest is not always a kind place.

The RWA’s Arboretum exhibition is shown alongside The British Wildlife Photography Awards, which are displayed in Bristol for the first time. Here we can see at last the wildlife that populates woods and forests and helps to make the trees seem alive. The humorous photography of a waving baby seal with sandy eyelashes and another image of a hungry vole are obvious highlights.

This photography collection is a rich contrast to the Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition, currently on display at The Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. There are just as many, if not more images of wildlife here at the RWA, and with just as many unusual angles and effects. For instance, Peter Cairns’ ‘Wild Woods Winter’ photograph has a striking Impressionistic effect created by an in-camera multi-exposure.

The third part to what’s currently on offer at the RWA is a small complimentary exhibition of paintings from the gallery’s permanent collection, called ‘Edge of a Wood’. This is in great contrast to the contemporary work in the main gallery for here there are sweeping traditional landscapes and clear Cezanne influences.

Refreshingly however, there is inclusion of trees and landscapes from other cultures. A pristine watercolour by Chien-Ying Chang RWA depicts a calm Chinese riverside scene, whilst a warm oil painting by Kit Gunton RWA from c.1978 illustrates a Mediterranean landscape complete with olive groves. These are important inclusions for thinking about what trees might mean in other cultures, which in turn is a frame through which political and ecological factors can be thought through.

All three exhibitions are open at the RWA until 8 March 2015.

[button link=”http://www.rwa.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/0000/00/arboretum/” newwindow=”yes”] Arboretum, RWA[/button]

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby