[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]L[/dropcap]ondon-based arebyte Gallery and the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo announce POWERPLAY, a group exhibition featuring artists working within digital media, moving image and technology.

The exhibition will be the first to show digital and new media art at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo, Harare and Mutare, and foregrounds the digital arts scene in Africa, presenting work by artists who are from or based in Nigeria, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the UK. Discussing the use of technology in creating a sense of identity and place within a digitised world, the artists look at the relationships of power experienced in varying ways. Taking place both online and offline, the multi-sited exhibition format brings to light the fluidity between the virtual and the real; how is power asserted over our decisions and movements, what are the consequences, and how can we think about control differently?

Through the use of existing infrastructure within the gallery and around the city, as well as the pseudo-advertisement aesthetics seen in the CGI printed works and the virtual reality iteration of the exhibition, the artworks proliferate and infiltrate this system to question our agency and power over surveillance and capitalism.

Tito Aderemi-Ibitola uses GIFs as a medium to make connections between migration and desirability of space, playing on the political categorisation of the term ‘alien’ and how the artist feels her own black body is read. This links to Isaac Kariuki who makes comparisons between the sale of counterfeit goods on the black market to the displacement of people living outside of the mainstream economy. Here, a connection to life and living is made between online and offline connections, whereby the inside and outside of normative roles are examined through Google Maps and trading on the dark web.

Also questioning copyright as a tool of power is Vincent Bezuidenhout and his work DVDRIP which originated during the rise of illegal file-sharing. In the spirit of Harun Farocki’s ‘operative images’ and aesthetically reminiscent of glitch art, he employs screen captures in order to highlight this phenomenon of the corruption of digital information. His other work Jsoc_pics consists of images appropriated from the Instagram accounts of members of Joint Special Operations Command, USA. The images are imbued with all the characteristics of traditional masculinity but the faces of the soldiers are redacted by the artist. This act of censorship reveals the elements of fear and shame often disassociated with toxic masculinity. By printing the images on the most basic elements of American consumerism (mugs, jigsaws, keychains, etc.), Bezuidenhout reduces the images to commodities and undermines the meaning of this kind of proliferation of the selfie in the process.

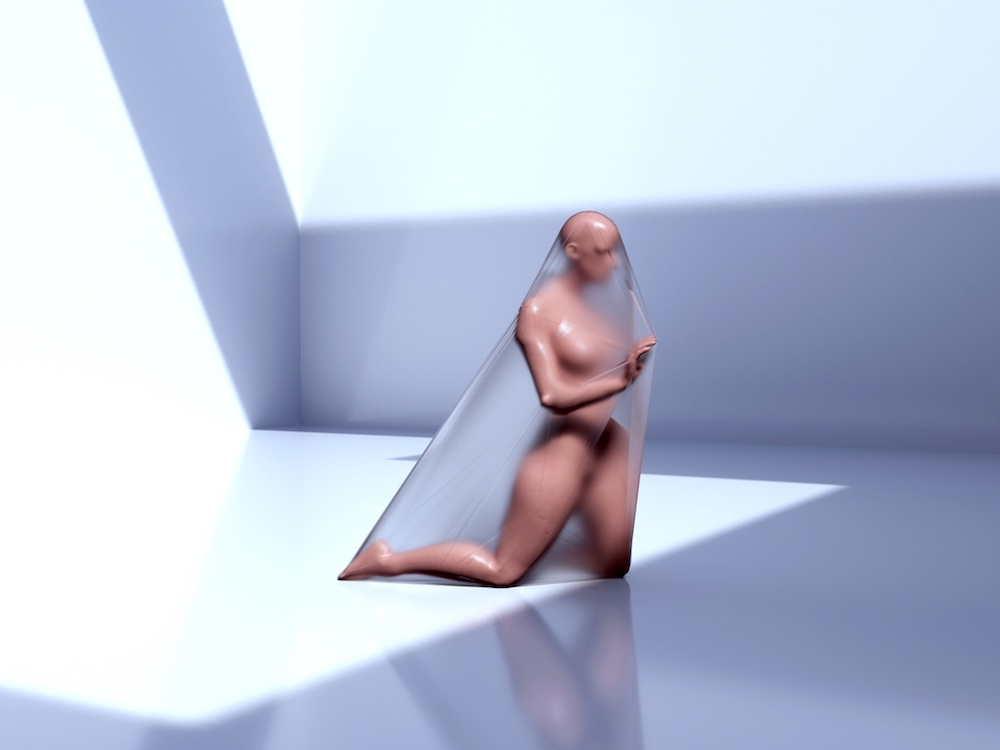

Scum Boy’s work shows avatars in various states of entrapment, both physically and mentally. Human emotion is expressed through a writhing body unable to comprehend the situation, and through positive movement in a body dancing in the acceptance of being powerless. Dance is brought into a different space with King Debs’ work whereby the power of gender and race is interrogated in a ritual performed by a woman figure through the artist’s male gaze. In the work, a young Tswana queen dances to appease the Bantu ancestors. The work opens and challenges the dialogue of the maltreatment of black women, who are instead celebrated here in the form of respect and appreciation.

Utilising language in the form of calligraphy, prayer and shapes is seen in both King Debs’ work and Kumbirai Makumbe, as they posit new ways of understanding a transcendence of the human. For Kumbirai, an unnamed protagonist talks to Eywa, an artificial intelligence, who assists in ascension of the body into code. The work more broadly looks at a non-exclusionary, new way of being, with an anti-hierarchical approach to the interconnectedness of people, ideas, and speculations on the future of society.

Mbakisi Sibanda’s work portrays the feeling of being isolated online whilst also being hyper-connected, in the form of a new video work and accompanying print identifying the dark nature of how the Internet affects mental and physical health, as well as social disintegration and social anxiety. Also taking an emotive response to power, Mr. Color’s large banner print tells the story of the creation of a new type of sentient android, where energy particles are formed from shared consciousness and transfer of energies between bodies. The work questions collectivity, and how positive and powerful energies can combine to create new ways of thinking.

POWERPLAY will be shown as a multimedia installation in arebyte Gallery. Throughout the duration of the physical exhibition, interviews with the artists will be available to view on arebyte on screen (AOS), the gallery’s digital art channel, as well as a virtual tour of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, made using Unreal software by UK-based artist Christopher MacInnes. The virtual reality version of the exhibition will then travel to the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Mutare and Harare.

POWERPLAY runs from 15 August – 26 September at arebyte Gallery, then travels to National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, in October. For further information, visit arebyte Gallery’s site here.

Image: Scum Boy, I Can’t, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Naila Scargill is the publisher and editor of horror journal Exquisite Terror. Holding a broad editorial background, she has worked with an eclectic variety of content, ranging from film and the counterculture, to political news and finance.