Born into a family of stone artisans in the dusty Mexican town of Tecali de Herrera, abstract painter Chantal Meza has recently been making her mark on the British art scene.

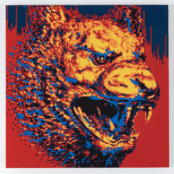

Meza is a self-taught painter who held her first major solo exhibition in Mexico when only 21 (at the Technology and Science Museum in Chiapas, 2010). Her earlier works are notably full of passion and intensity, drawing explicitly upon personal experiences of anxiety, fear and pain. In 2017, however, something changed, as she became more sensitised to the social and political landscape in Mexico. “I didn’t consciously seek out a problem or went (sic) in some kind of search for an issue that I could attach my art to,” Meza explains. “The problem of violence came to me, and once it appeared I couldn’t ignore it.”

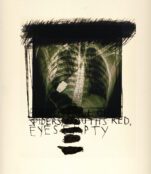

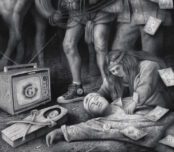

Meza started to feel the weight of her country’s history, especially the ongoing phenomenon of enforced disappearances. These, dating back to the late 1960s, had taken on new meaning with the arrival of the War on Drugs and the increased power of the narco-trafficking cartels.

On the subject, Meza reflects, “Disappearance is marked by a devastating absence. It constitutes a form of violence that rips open a wound in time. It offers no viable recovery and no meaningful justice. And for those who are left to live, the terror is unending. Sometimes words fail us, we need another language and so we create art because that speaks differently.”

Meza’s turn to explicit political issues was perhaps inevitable, given the ongoing violence and issues affecting her country. Yet she was still mindful of the pitfalls and the ever pressing need to retain the integrity of art.

“When I looked at what was going on in my country, I saw problems that were evidently affecting young female Mexicans that made us seem vulnerable,” she explains. “I have, however, been reluctant to present myself as some feminist Mexican artist who embodies vulnerability just for the sake of improving my chances. Yes, I am female. And yes, I am Mexican. But I don’t want to label my art or, worse, attach a label so that the work is already framed and painted over with a political truth. In Mexico we learn very quickly the difference between compelling art and propaganda. Moreover, when I paint, I don’t believe it comes from a position of vulnerability. On the contrary.”

Meza has seen her reputation grow and has found a receptive audience for her work within universities. She has delivered a number of public lectures at prestigious institutions such as Harvard University, McMaster University, Ontario, and the École Normale Supérieure in Paris.

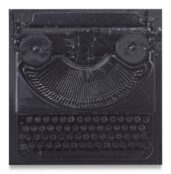

One notable outcome from this attention was the production of the book, State of Disappearance (2023), published by McGill-Queen’s University Press and Featuring all the artworks Chantal created for her series of the same name, the book saw a number of the world’s leading thinkers offer essays reflecting on her work, including Henry Giroux, Gil Anidjar, Adrian Parr and David Theo Goldberg.‘State of Disappearance’ was the title also given to Meza’s Arts Council funded exhibition held at Centrespace Gallery in Bristol in the autumn/winter of 2023. Running for a number of weeks, not only did the exhibition draw a few thousand visitors, it was also host to a series of public talks from authorities on different aspects of disappearance, including Professor Richard English, Professor of Politics and Director of the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice at Queen’s University of Belfast; and the Sunday Times best-selling author Lucy Easthope. English described the exhibition as… (read the full article in Trebuchet 15)

Read more in

Trebuchet 15: Installation

Featuring:

Installations as theatre

Giuseppe Penone

Michael Landy

Annette Messager

Karolina Halatek

Sounds Art as Installation

Jean Boghossian

Jon Kipps

Chantal Meza

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle