[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]prinkles, ketchup, charcuterie, beer, bread, jam, pasta, pickles, candy, sushi, pizza, ice cream, dumplings, oysters and art are considered by many not worth making at home. These items, people say, should be bought instead because their production involves smelly, time consuming processes, and the result is sometimes disappointing when compared to the outcome we have in mind. In the series of aforementioned elements, there is however one that doesn’t quite fit on the list, and yet is consumed with the same voracity as the rest: art.

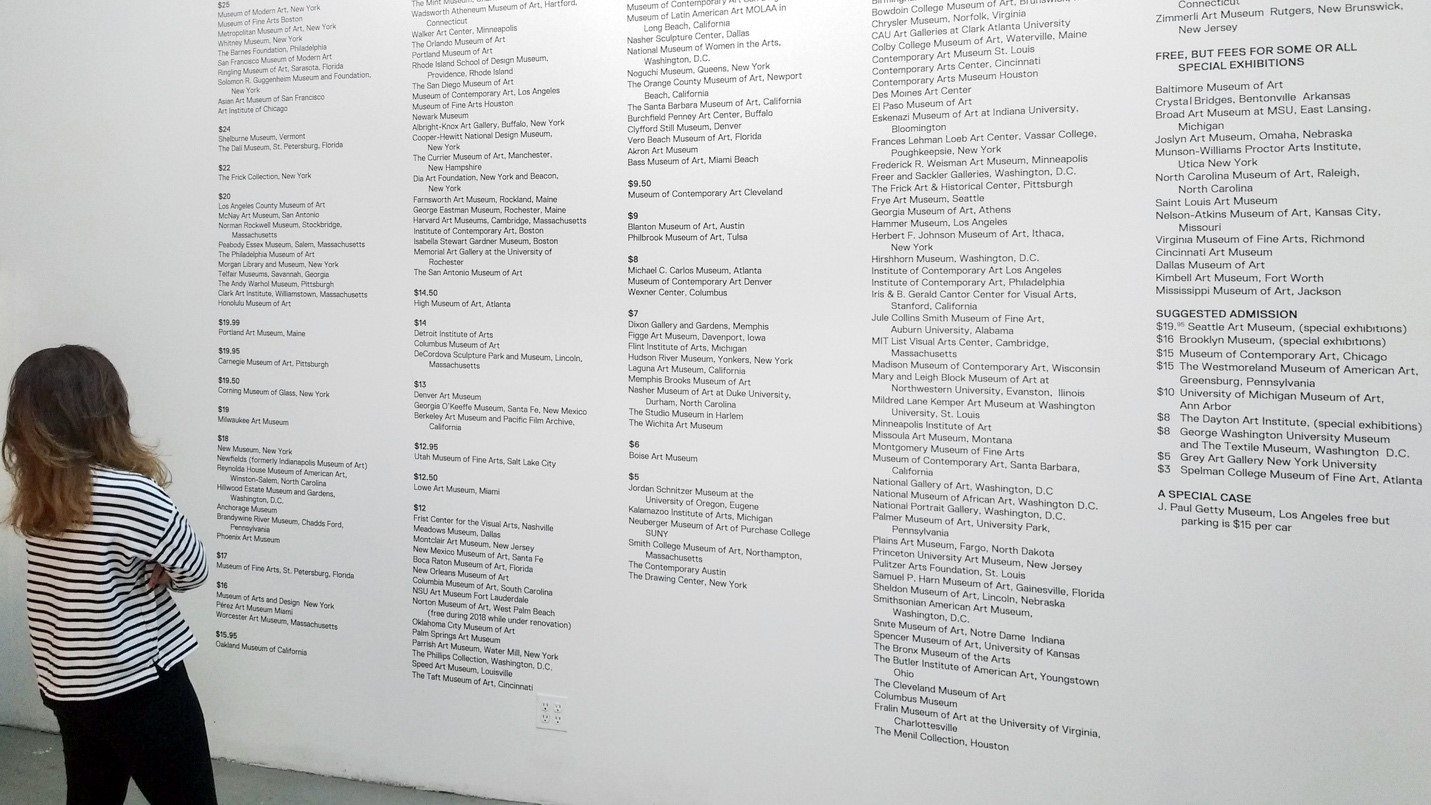

Seeing the consumption of art at the same level as the consumption of ketchup or sprinkles might seem shocking. However, when looking at the price menu of my favorite ice cream shop I realize that it bears a striking resemblance to choosing what museum to visit from the museum price list that Raul Valverde created in his Cultural Portrait (US museums by admission price) at the International Studio & Curatorial Program showed during the last 2018 Spring Open Studios (April 27-28).

‘Cultural Portrait (US museums by admission price)’ Raúl Valverde, 2018. Wall text, variable dimensions

Consumption is inevitable in most aspects of life but it is only one side of art, and it is not even the most important one. While museums preserve, acquire and make accessible (sometimes through admission fees) art that has been considered of public interest, the most important dimension of art is always on the house. Art springs everywhere in the events of simple everyday life. Art has a deep connection to the human experience as it “satisfies the inescapable human hunger for imagined experience in all of its imaginable variations”(1) Art is a precondition of the human existence: a necessity. (2)

Seeing art only as a material possession relegates it to the service of other elements of life. Malevich considered that “this state of affairs is curiously inconsistent with the fact that art always and under all circumstances plays the decisive role in the creative life and that art values alone are absolute and endure forever.”(3) Hale Woodruff understood that “we may not always see life as art but we can most certainly see life through art. Nor is there any denying that art springs from life, from what we are, what we do, what we love and cherish, what we hope to be, and what we dream.” (4)

There are many places in which a house

that intertwines art and life is necessary

but first we need to build it in our minds

Kandinsky, for his part, felt that the greatest revelation is to realize that all realms of life have never been “so strongly tied together and never so sharply divided.”(5) The place where “the interrelationships of these individual realms were illuminated as by a flash of lighting” (6) is one of the places where art is fully integrated in everyday living: the house.

There are houses where art and life have been fully intertwined because of the way their owners have inhabited them. In this article I want to discuss the myth of a house that has disappeared, the discovery of one that still exists and the challenge of one that will hopefully exist one day in the future.

The house that no longer exists was on 123 West 10 Street in New York City. There, artists Marguerite and William Zorach along with their daughter Dahlov and son Tessim experienced a consuming drive to live through art from 1913 to 1937. The “atmosphere of absolute unconventionality and freedom” (7) that Marguerite valued in Modern art ruled in the everyday activities of the Zorach family.

‘Home Scene’ Marguerite Zorach (circa 1924), courtesy of the Zorach Collection, LLC

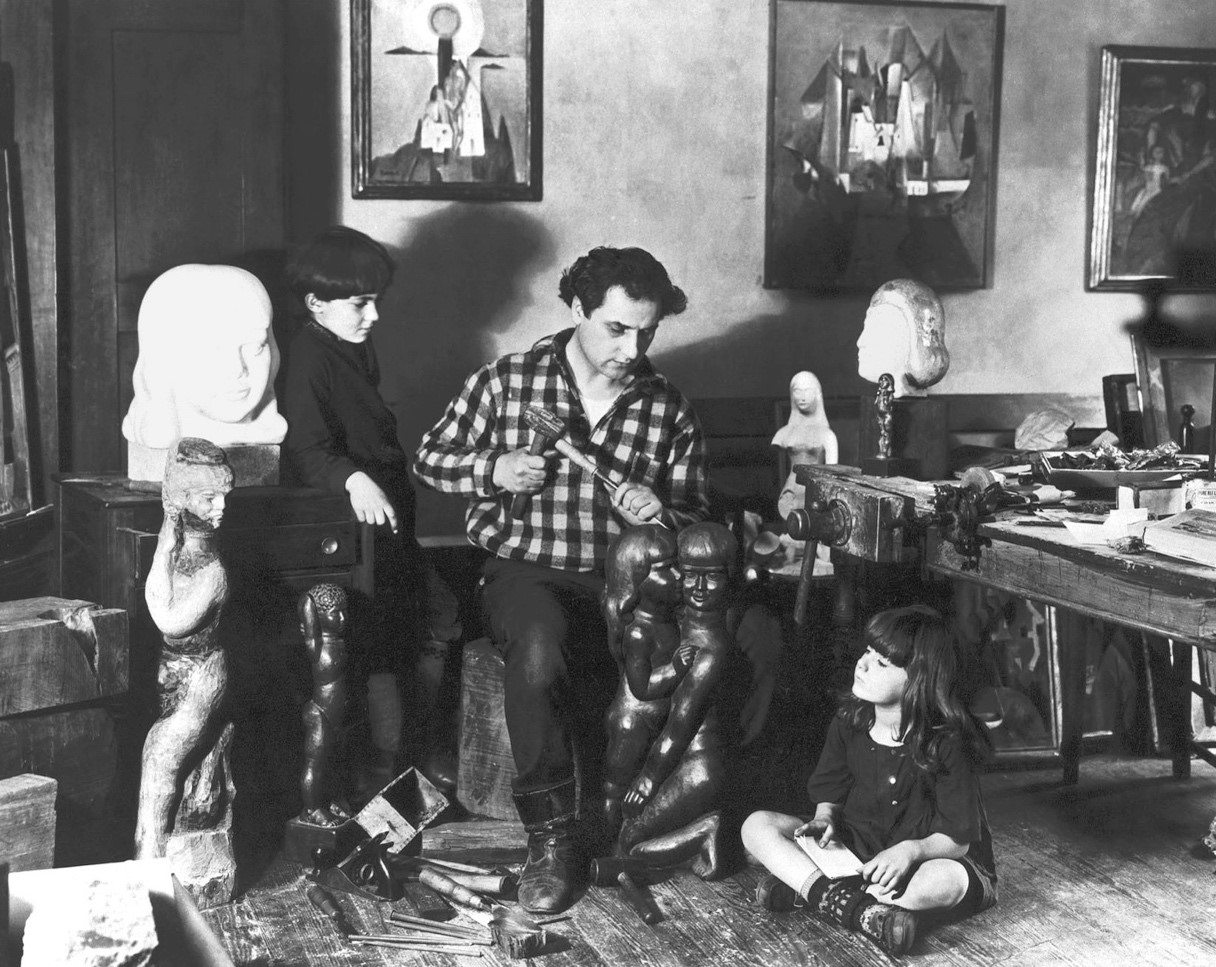

Marguerite was always busy making batiks, embroidering bedspreads, clothes, hooking rugs, and painting pictures. Although William might be busy carving, he could take time out to make,“a costume for Hallowe’en, all covered with moons and stars and blazing suns of genuine gold leaf” (8) for her daughter. In this environment, William pursued his life-long study that he described as the embodiment and expression of the love of a father for his family.(9) Tessim realized very early that behind the joy of creative production, the family was constantly struggling economically.

‘William Zorach with Tessim and Dahlov at 123 West 10th Street in Greenwich Village’, New York City, 1924, photographer unknown, courtesy of the Zorach Collection, LLC

Despite having pinched finances, the Zorachs came up with ways of transforming their humble apartment into “a house of wonders”(10) Marguerite explained that they “didn’t have any money to buy furniture in those days” so they “picked up little odds and ends—a chair on the street, or something here and there, for a few cents”(11) . Later they would paint them with bright colours. The kitchen wall got dirty, so they “decided the only thing to do was to paint murals over it and then nobody would know it was dirty”(12).

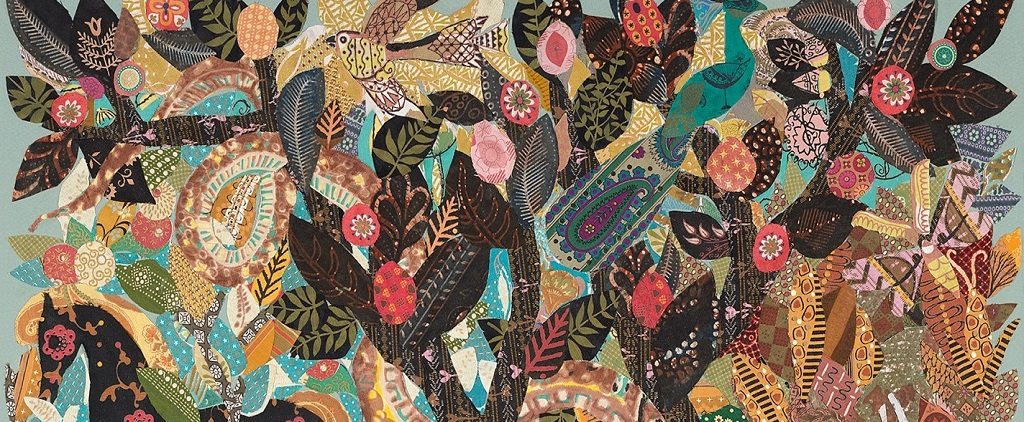

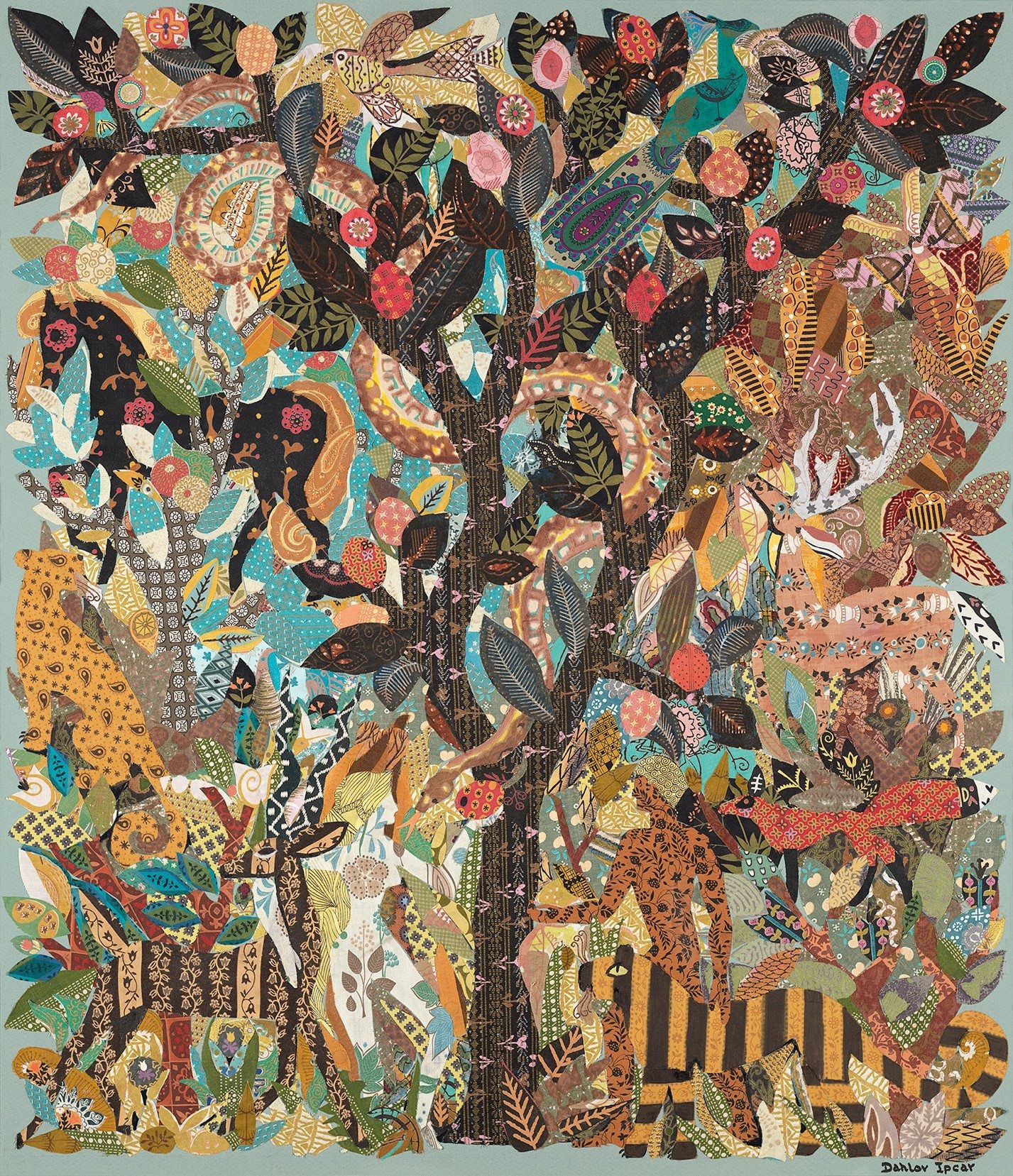

The house’s floors were lead red and the walls lemon yellow. They made their little hall into a Garden of Eden mural, with a life-sized Adam and Eve and a red-and-white snake draped around the trunk of a decorative tree, with tropical foliage surrounding it all. William considered that there was nothing like their house in the country at the time. The Garden of Eden murals eventually disappeared but looking at Dahlov’s treatment of the same subject there is an opportunity to imagine how it might have been.

‘Garden of Eden’ Dahlov Ipcar, 1961, cloth collage, 37 x 32 inches

In this atmosphere, Dahlov evolved creatively and at the age of 21 became the first woman and the youngest person to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition titled Creative Growth: Childhood to Maturity was curated by Victor D’Amico, whose house is another case in which art and life was experienced as the same thing. In contrast to the Zorach house on 123 West 10 Street, the D’Amico house still exists and it is the second house to discover.

It will be about being able to share

a creative part of ourselves in

whatever we do in life

Victor and his wife Mabel had a lifelong commitment to art education. They explored the essence of the art experience as spiritual involvement, and the ability to communicate one’s most profound ideas and emotions through aesthetic expression. They considered that the individual’s personality had to be respected and developed by providing opportunities for creative experimentation. Mabel had headed the art department at the Rye, New York, high school and was an experienced nature pioneer. She believed that “art should become for all young people, regardless of their ability, a form of expression which they will use naturally and unselfconsciously throughout their lives” (13). Victor was the founding director of education at the Museum of Modern Art from 1937 to 1969. He developed programs for all kinds of people: children, adults, war veterans and other community members.

Mabel D’Amico’s studio at the House and Archive in Lazy Point, Amagansett, New York, undated, Jenny Gorman, courtesy of The Victor D’Amico Institute of Art.

The D’Amicos bought a house at Napeague’s Lazy Point (New York) area (14) in 1940. The setting had what they considered necessary for creativity to flourish. The beach, sky and sand were an inspiration as well as an endless source of objects to use in their artworks. The house’s original structure however was poor. The couple had to rebuild the house at a time when resources were scarce due to World War II. They had to use old wood and nails, dislodging the nails from the original house and hammering them straight. Despite the difficulties, they succeeded in building one of the first modern homes in the area.

Mabel and Victor D’Amico (undated), photographer unknown, courtesy of The Victor D’Amico Institute of Art

The house was only their first building accomplishment. Victor wanted to create an art school to serve the local population and he was looking for a place “more dramatic and reflecting the character of the environment – sky, sea and salt air, either a boat, or resembling one.” He found a World War I, 500-ton Navy barge in an abandoned New Jersey harbor. In 1960, he and some local fishermen towed it up the East River, through Hell’s Gate and into Long Island Sound to the shore of Napeague Harbor. The school came to be known as The Art Barge.

The Art Barge, Amagansett, New York, 2018, courtesy of The Victor D’Amico Institute of Art. Photographer Esperanza Leon.

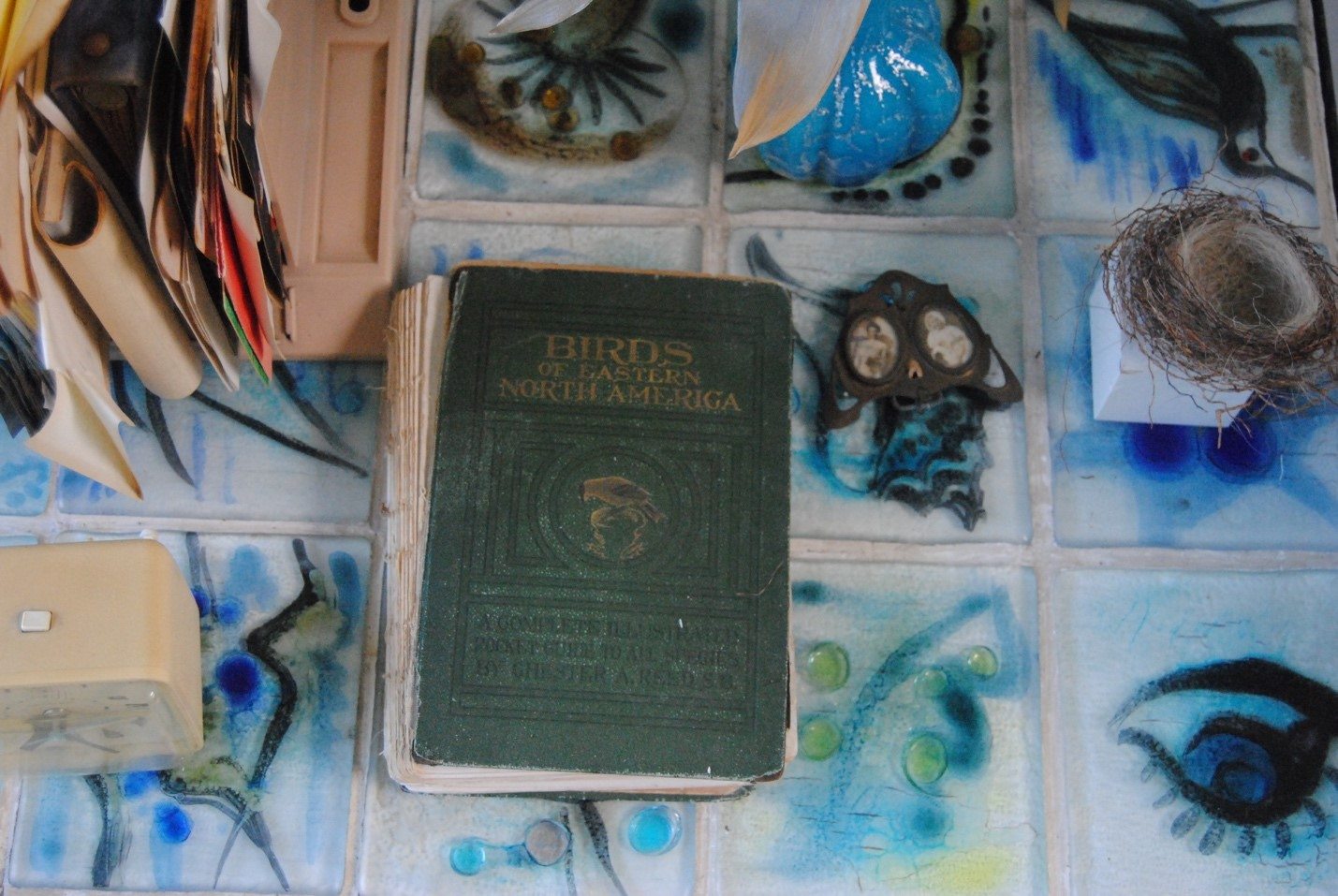

The D’Amicos passed away but their house and Art Barge still stands to remind us the role that art can play in our lives. Now known as The Mabel and Victor D’Amico Studio and Archive, it comprises an extensive collection of research materials–photos, films, articles, books, motivational materials–and artwork. From early modernist architecture and furnishings to found-art sculptures and collected items, The House contains many treasures from the private world of the D’Amicos.

Table at the Mabel and Victor D’Amico House and Archive in Lazy Point, Amagansett, New York, 2017, photographer Sara Torres Vega.

In visiting the Zorach house with our imagination and the D’Amicos’ house physically, there is an invitation for all kinds of people to build a third house. This house should be built where art is of secondary or indeed no importance in people’s lives. There are many places in which a house that intertwines art and life is necessary but first we need to build it in our minds. Then, hopefully, that imagined house will find its way to everybody’s homes. There, art will be on the house which means it will neither be for free nor for sale. It means it will be an act of generosity. It will be about being able to share a creative part of ourselves in whatever we do in life.

Maybe sprinkles, ketchup, charcuterie, beer, bread, jam, pasta, pickles, candy, sushi, pizza, ice cream, dumplings and oysters are really not worth making at home (or maybe they are!), but not making art would be a terrible mistake. And I know art smells on occasions, it is time consuming and the result is sometimes disappointing when compared to the outcome we had in mind. But it is the opportunity to develop our own unique way of looking at the beauty and excitement of simple everyday life. For that I think, it is worth the try.

__________________________________________________

Notes

1. Scharfstein, B. (2009). Art without borders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.p.3).

2. D’Amico, V. (1961). Art, a Human Necessity. School Arts, February 1961. The Museum of Modern Art Archives. R&P 14.5

3. Malevich (1927) The Constructive Idea in Art. in Robert, H. (1964) Modern Artists on Art. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p.97

4. Woodruff, H. (1959) Committee on art education The Art in Art Education, 17th Annual Conference of the National Committee on Art Education, p. 50

5. Kandinsky (1913) Reminiscences in Robert, H. (1964) Modern Artists on Art. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p.38

6. Kandinsky (1913) Reminiscences in Robert, H. (1964) Modern Artists on Art. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p.38

7. Zorach, M., & Burk, E. (2009). Clever Fresno girl. Newark, Del.: University of Delaware Press. p. 26

8. Ipcar, D. (n. d.). Something about the author. Autobiography Series. Volume 8. Gale Research Company. Book Tower. Detroit, Michigan 48226. p. 136

9. Zorach, W., & Zorach, M. (1979). Reminiscences of Willam and Marguerite Zorach: oral history. New York City: Columbia University oral history collection, part IV, published by Meckler Publishing, Westport, CT. p. 161

10. Ipcar, D. (n. d.). Something about the author. Autobiography Series. Volume 8. Gale Research Company. Book Tower. Detroit, Michigan 48226. p. 13

11. Zorach, W., & Zorach, M. Reminiscences. p. 262

12. Zorach, W., & Zorach, M. Reminiscences. p. 262

13. Vvaa. (1943) I believe… by 31 Art Teachers. New York: The Committee on Art in American Education and Society

14. Wolberg, M. (2018). The Mabel And Victor D’Amico House In Amagansett, Where Art And Life Converge. 27East. Retrieved from http://www.27east.com/news/article.cfm/Amagansett/63395/The-Mabel-And-Victor-DAmico-House-In-Amagansett-Where-Art-And-Life-Converge

Sara Torres Vega is a teaching artist and researcher. Her training is in fine art, with a focus on educational, relational, and participatory practices that have art as a catalyst for social connectivity. She got her Ph.D. in 2016 at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Complutense University of Madrid. She has been a visiting researcher at Tate London and New York University and has worked at the Museum of Modern Art. She has given talks at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), New York University, Culturgest (Lisbon), the Bergen Academy of Art and Design, Fundación Telefónica (Spain), and the Tate (London).