Of all that is written, I love only what a person hath written with his blood.

Write with blood, and thou wilt find that blood is spirit.

It is no easy task to understand unfamiliar blood.

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

Are our lives puzzles to be somehow understood? Does self-mastery follow from such an understanding? Is the art of life a revealing of truths buried deep within each of us? If so, which is the path inward – psychoanalysis, past life therapy, an MRI, or art? What follows is an examination of one approach.

Our story, as related by its protagonist, Axel Stocks (1946-2015), begins with his mother, shortly after she was married. She and her husband were young and very much in love. Unfortunately for the newly-weds, the year was 1939, they were in Poland, and they were Jews.

In September of that year, the German army initiated its program of world conquest with a Blitzkrieg – a “lightning war” – which quickly toppled the atavistic Polish monarchy and placed the country under its dominion. Her husband, his entire family, and her whole family were hunted down by the S.S. and systematically murdered in concentration camps. She later confided to her son that she was repeatedly raped by her captors under constant threat of death. Everyone around her was killed.

After the war, she was resettled in a displaced persons camp and it was there that Axel was born to her in 1946. Once she and the child were nursed to health, they moved briefly to Berlin before emigrating by boat to Florida. A single mother alone in a new country and fully traumatized, she soon took up with a man who would become her second husband and a caring stepfather to the young child. Stocks knew that this man was not his biological father, and the mystery of his parentage would forever haunt him. As an adolescent, Axel would lie in bed at night struggling to envision his mother’s lost husband, hoping that he had conceived Stocks before his execution, and wrestled with the notion that he may have been born from the rape of his mother by her Nazi captors. Did he dare conjure the faces of the Nazis? Was he born of love or hate? If he was born in love, then his birth was tragic, but if he was born of hate, his birth was a stain on the human race. Deep down, he felt at war with himself. On the inside, he was half-victim and half-executioner, while on the outside, with his stepfather, he looked like just another kid. A boy with three fathers, his was a complex and unsettling legacy. What was he to do?

As a teenager, Stocks’s family moved to suburban New Jersey, where he met Bruce Springsteen and Debbie Harry, but he found his calling upon visiting Greenwich Village in 1967. There and then he met Hugh Nanton Romney Jr., better known to the world as “Wavy Gravy.” Gravy was an acid head who, preaching the then-trendy gospel of LSD, psychedelicized Stocks, who afterward took up making trippy jewelry and dressing like a wizard with a Jesus complex. In a sense, he felt “reborn,” but the repressed has a way of returning in sometimes surprising ways, as irony is a powerful force in the universe. Over time, Stocks’s jewelry became somewhat popular, and he was introduced to Salvador Dali, who was then living at the St. Regis Hotel in New York City.

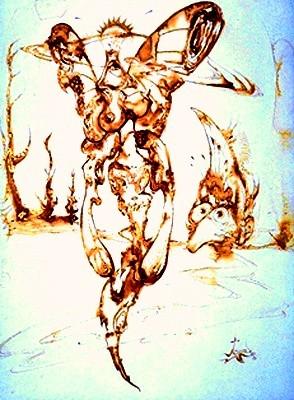

Sensing something peculiar, Dali took an immediate interest in Stocks, and asked him about his life. After Stocks related his life-story, Dali pronounced that, from thenceforth, Stocks was to paint with his own blood. The two then consecrated their encounter with a hemoglobin-rich round robin of exquisite corpse. While Stocks continued to make jewelry, eventually selling some rings to Keith Richards and Lady Gaga, among others, he also created a body of at least a hundred blood paintings, taking his inspiration directly from Dali.

The mystery of Stocks’s parentage was understood by Dali to be a defining trauma, a fount of artistic inspiration pouring forth from within, fully authentic and certain, yet also mysterious and painful. It would be somewhat ironic that what had until then been most difficult for Stocks to face would be the substance of his aesthetic for over forty years. On one level, this is a story about using blood to make art, but on a deeper level, it is about making art out of one’s primary formative experience – tapping the scar that sets us apart from the pack as a creative wellspring. Unlike many other artists who have used blood as a medium to express their artistic vision, Stocks used his artistic vision to express his blood. In his own words, he was “looking to find [him]self.” (A Blood Artist, 2020)

Born from the rape of his mother by her Nazi captors. Did he dare conjure the faces of the Nazis?

Dali was also on point regarding the centrality of blood in the large-scale events framing Stocks’s life. As Robert Jay Lifton forcefully demonstrated, National Socialist German Workers’ (aka “Nazi”) Party ideology was a form of identity politics springing out of a “biomedical vision.” (Lifton, 1986) Nazi citizenship was defined as a Bluteinheir (“unity of blood”), with Hitler referring to his compatriots as “people of German blood” in public oratory. Blood also ran deep in popular Nazi shibboleths: Blut und Boden “Blood and Soil” was a military slogan and Blut und Ehre (“Blood and Honor”) was integral to the culture of Hitler Youth. As a form of biological contagion, the Jewish menace was to be eliminated in an escalating campaign, beginning with purges from civil service, boycotts, book burning, public humiliation, and hooliganism, and culminating in an archipelago of death camps that were to stretch from Eastern Europe to Nablus and beyond. (Klaus-Michael Mallmann et al., 2010, pp. 89-90, Cohen, 2014)

In Mein Kampf, Hitler laments Jewish contamination of the German body politic. (Hitler, 1925 p. 305.) The sanguinary roots of Nazi politics were spelled out in the Programme of the Nazi Party, 24 February 1920, and later codified in the “Nuremberg Laws” of September 1935: the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. (Goldhagen, 1996, pp. 97-98.) Even before its rise to power, the Programme of the Nazi Party was explicit: “Only those of German blood…may be members of the nation. Accordingly, no Jew may be a member of the nation.” The very first laws passed by the Reichstag upon the Nazi rise to power in 1935 would instill this principle into the foundational laws at the very heart of the Third Reich. The Reich Citizenship Law’s second article defined Germans primarily by their sanguine commonality: “A citizen of the Reich may be only one who is of German or kindred blood…” The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor was no less direct: “Moved by the understanding that purity of the German Blood is the essential condition for the continued existence of the German people…Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden.” Under this law, Stocks would have fared no better than his mother’s family: “Extramarital intercourse between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood is forbidden.”

Establishment of the German Institute for Blood Group Research was, thus, a direct, practical outcome born of the Nuremberg Laws. Nazi scientists combined anthropology with a mystical celebration of the primordial German volk (“nation) in Seroanthropology – the study of ethnic difference in blood so as to harness the spiritual power of blood for political ends. (Boaz, 2009) During the “Beer Hall Putsch,” their failed attempt to seize sovereign territory, standard bearers of a swastika-embroidered flag were killed, and their blood stained the flag. The Blutfahne (“Blood Flag”), as it was then known, became a fetish transubstantiating the will to power and national identity. At the Nuremberg rallies, Hitler himself would extend the Blutfahne to heiligen “sanctify” other Nazi banners with the blood of these fallen martyrs. (The destiny of the Blutfahne is unknown as it has not been seen since 1944.)

Of course, Stocks was far from the first and is already not the last artist to deploy blood in art. The moment when humans first saw blood as pigment, and not merely as an indicator of danger, illness, or fertility, was surely a major development in our phenomenological evolution. Cave drawings often combined blood with clay, minerals, water, urine, animal fat, bone marrow, vegetable matter, ground wood, charcoal, and eggs. Blood proteins in some of these works of art have been dated back to 20,000 years. (Bunney, 1990)

Over the years since, many peoples have used blood – usually the blood of animals – as an additive to paint for sacred rituals and, in the use of war paint, to also intimidate rivals and inspire themselves. Many artists in recent times have used blood to intensify their work, explore the macabre, and/or score political points, notably: Hermann Nitsch and the Viennese Actionists; menstrual artists like Judy Chicago and Lani Beloso; the art corporel of Michel Journiac and Gina Pane; Ron Athey, Barton Lidice Benes, Jordan Eagles, and Andres Serrano in the age of AIDS; bodily expressive contemporary artists like Franko B. (Franco Bosisio) and Elito Circa; live performances by musicians including Glenn Danzig and Gorgoroth; etc.

According to Stocks, his first step toward blood painting was securing cooperative doctors to prescribe (and periodically renew) a good bit of anti-coagulant, despite the fact that he did not have a medical condition which required it. From the look of his paintings, at least some of them consumed a considerable amount of blood, and Stocks’s pale visage seems as if it was blanched by the process. He would slice a small cut in one of his fingers, alternating between squeezing it to increase blood flow and letting it drip into a test tube. Then, he would add the blood thinner to prevent it from coagulating and to create the consistency he desired. The admixture could be stored in a refrigerator when he wasn’t painting. Crucially for Stocks’s technique, which alternated between classical and surrealistic styles, his primary painting implements were fountain pens. Fountain pens allowed him to alternatively draw fine detail or crank out puffy clouds that could be shaped by the pen before it dried.

Given its source and inspiration, one might expect Stock’s oeuvre to feature grim subject matter, and, indeed, most of his self-referential work is emotionally and thematically intense. He created many paintings of himself in anguish and he is often depicted crucified. Another recurrent theme are fetuses, some of which are also crucified, and he referred to this series of paintings as “foetal-istic.” One such painting portrays a cross section of a human womb, including a foetus emblazoned with a large swastika on its oversized head to represent Axel’s point of origin in a concentration camp.

While Stocks did, indeed, often use his art to explicitly thematize his life, his work is also, at times, playful, fantastic, and frequently charged with a bizarre eroticism. Women are often sexualized with breasts well beyond proportion, and presented as if they were partially another species, among them, bats, birds, angels, demons, cats, and butterflies. Anthropomorphic female butterflies are so common in his work that he produced a whole series he referred to as “blooderflies.” Stocks’s own sexuality is reflected in a series of paintings which envision him masturbating tremendously outsized erections while seated on a toilet. In one work, his penis ejaculates blood, symbolizing his seed being supplanted by his blood; his life overwhelmed by its prehistory, his DNA as the sorry site of the crime that framed his life. He died without progeny.

Blood runs within each of us in parallel currents, and it flows though us, cascading across generations, gushing through time, from a vastly remote source. On the inside, we are cells sucking on cells so delicate they must be suspended in a supportive ooze not unlike the primordial soup that gave birth to life, and flowing through chambers and gullies not unlike the xylem and phloem girding our botanical cousins. Blood is the past running through us, carrying a genetic cargo on a mission – reproductive, kamikaze, illuminative, laboring, vainglorious – merging into other currents, spinning in eddies, and eventually running dry. Does it belong to us or do we belong to it? (Dawkins, 1976) Axel Stocks attempted a voyage upstream, through his blood and toward his point of origin, even as his actual life flowed away from it. Whether his quest to swim upstream yielded insight into his place in the world I will leave to the viewer to surmise.

“It is the blood that makes atonement.” – Leviticus, 17.11

References

A Blood Artist (2020) [film] Directed by J. Wengrofsky. New York City (US): Syndicate of Human Image Traffickers. http://www.humansyndicate.com/axel-2/

Boaz, R. E. (2009) “The Search for Aryan Blood: Seroanthropology in Weimar and National Socialist Germany,” Dissertation, Department of History, Kent State University.

Bunney, S. (1990) Science: Ancient artists painted with human blood. [online] New Scientist. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12517102-700-science-ancient-artists-painted-with-human-blood/. [Accessed 10 Jul. 2020].

Cohen, E. (2014) The Grand Mufti’s Nazi Connection. [online] The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Available at: https://www.jpost.com/opinion/op-ed-contributors/the-grand-muftis-nazi-connection-347823 [Accessed 10 Jul. 2020].

Dawkins, R. (1976) The Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, New York.

Goldhagen, D.J. (1996) Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Hitler, A. (1925 [1943]) Mein Kampf [Trans. R. Manheim] Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company

Lifton, R.J. 1986. The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, Books, New York.

Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Cüppers, M., and Smith, K. (2010). Nazi Palestine: the Plans for the Extermination of the

Jews in Palestine. New York: Enigma Books.

All images courtesy of Leslie Barany. © Leslie Barany 2020

New Yorker Jeffrey Wengrofsky has served on the staffs of Aperture magazine, Coilhouse, and Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory. Also a filmmaker and festival curator, Wengrofsky is now preparing to curate a night of films at the Babylon Kino in Berlin (date TBA). He now has open calls for films for Secrets of the Dead, to be held in NYC in October 2020, and Secret Treaties: Strange Political Bedfellows in 2021. Submit via FilmFreeway. His new film is A BLOOD ARTIST: www.humansyndicate.com/axel-2