Because of our three brains – the cortex, the limbic and the reptilian – we hardly know what we really want and like.

Of course, sex, food and domination are the most deeply rooted and primordial interests of the brain zoo. Time-honoured food, aggressive and sexual instincts prevail in most circumstances. But that is not enough to we “triple-brained” humans – we want to use our ability to think and to reason.

Sometimes we like to delve into the intricate problems. This is why we love detective stories. And in general we are pulled into any well made movie because we try to guess what is going on and to predict what will happen next. We wonder how the hero will wriggle out of swelling difficulties and problems. One of the brain’s pleasures is to get new experiences, to learn something potentially advantageous.

When someone in our view works on difficult problems, figures out how to understand something important, we mark and inwardly digest the same things. And the brain is pleased that we gained useful experience which contributes to our survival, “free of charge”. When the brain acquires new knowledge its reward centres receive the “hormone of happiness”: dopamine. That is why the brain is drawn to new adventures (real or virtual) in books, or on cinema and TV.

Recent research from the California Institute of Technology aimed to determine whether avoidance of an aversive outcome recruits the same neural circuitry as that elicited by a reward itself. Participants’ brains had been scanned with functional MRI while they performed choice tasks. In each trial they chose from one of two actions in order to either win money, or avoid losing money.

Our behavior is always guided by reward and punishment “centres” in the brain to obtain positive outcomes and avoid negative consequences. Emotional states are created by external rewards and punishments. The abovementioned study demonstrated that avoidance of an aversive outcome recruits the same neural circuitry as that elicited by a reward itself.

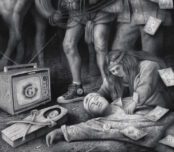

That is a well-known principle: “If you want to make somebody feel much better, do something awful to him, and then return him to what was before.” Therefore, to create pleasuring catharsis for mind and body, drag the movie hero through myriad complexities and keep him on the cusp of an inevitable/indivertible/inextricable situation. And then at the last moment the hero, by a fluke, avoids the worst.

All things came out fine. The danger was extricated, the situation settled down – and the viewer’s brain wallows in pleasuring endorphins.

A tearful audience stares at the titles, trying to memorize the name of the director to ensure they don’t miss his next film.