Nestled in the midst of the Dolomites, in an autonomous community of Northern Italy, is art set in a dream? The Biennale Gherdëina is a precious event. The mere presence of fairy tale towns like Ortisei and Bergamo, set so precariously amid precipitous mountains, is a statement of humanity’s drive to escape and immerse itself in nature (if only to discover what it is to be alive).

2024 sees the ninth Biennale Gherdëina find guiding inspiration in the Ladin legend of the Fanes. The tale tells of a people cursed when they abandon their connection to their wild Marmot ancestors, eventually returning to live beneath the land until a portentous time of their re-emergence.

The provenance of these myths suggests deep roots back to prehistory; stories forming the connective human narrative of the area. Festival curator Lorenzo Giusti suggests the power of the story lies in the detail that ‘they are totemic structures that tell of the complex relationship of these archaic societies with the theme of the soul, whose presence pervades all the main entities of living nature in its freest and wildest dimension’ (BG9 Guide).

Such a profound and fantastic gloss of this story, eyebrow-raising on paper, comes into its own while walking along ancient cobbles between high-roofed alpine buildings. The low-sweeping eaves of the buildings emphasise the stalwart cliff faces, made more mysterious still by wafting banks of mist and cloud. This close to the elements, perhaps all is indeed open, wild and true-eyed? Perhaps there is something to be found by following the guidebook like a treasure map, where artists’ works reflect totemic connections between human nature and the environment.

It’s easy to find such conjecture plausible in the drama of the surroundings; the sheer mountains looming, judging, sheltering and threatening; the babbling brooks and raging rivers; the ever rolling mists and the sturdy alpine buildings with their tight roof angles pointing skyward. All are signals of a place, and what elements life here must contend with.

Picking up on natural social cues, the exhibitions were housed in locations either directly or thematically linked with local inspirations. Featured artists presented works either commissioned specifically for the event or had works included because of their relevance, whether local or topical. While the majority of the works were shown within an easy ramble around the town of Ortisei, a few artists had their works set at a distance requiring long walks or amenable taxis. The farthest were displayed in small villages outside of Bergamo.

This expansive layout presents the works as more regional than centralised. The visitor is required to explore, experiencing valley to valley differences rather than bashing through the programme over the course of a big day.

Following a pathway-cum-stream towards The Parliament of Marmots (the name of a plateau where the Fane legend suggests the ancestors reside) is where the visitor starts to fully appreciate the landscape. Snow-capped cliff faces float through gaps in the cloud above the verdant glow of late spring fields tumbling to the valley floor. Small streams gather and merge into tumble drier torrents of meltwater. Wild flowers gleam with high-altitude psychedelic colour. Emerging onto a flattish expanse, a wooden skeleton of an aquatic dinosaur extends in a gully.

The work, by Ingela Ihrman (First Came the Ocean, 2024. Commission), touches on the history of Ortesei by using its core resource (until ski-tourism): wood. Using trees weakened by the bark beetle epidemic and felled by storms, the piece references the region’s craftspeople’s precarious symbiosis with the local ecology.

The Dolomites themselves are rich in marine fossils and this synergistic play on economy, ecology and geology gives the work a worn-in feel, reflected in the weathered alpine huts dotting the mountainside. The effect of the piece, after the steep walk through closed forest to the open plateau, has a self conscious mirroring aspect. Why make art here? It’s hard to imagine improving on the natural beauty of the setting itself. Nevertheless, art serves to raise our awareness from the micro to the macro, and Ihrman’s piece makes the case that art creates ‘nature’ with a conscious depth that’s lacking in the act of instagramming spectacular views as a backdrop for the ego.

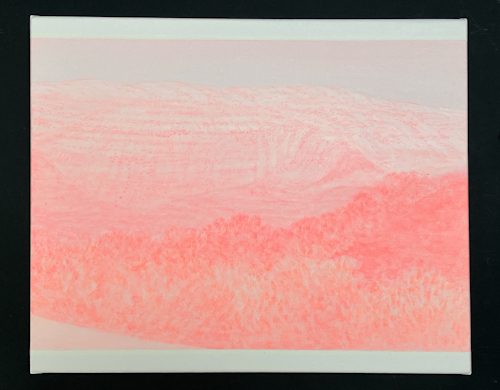

Apparitional Mountains (pink) I-XX (Series of 20 paintings, 2023-24) by Daniele Genadry takes our perception of nature, whether informed by photography or painting, as its starting point and asks us to reflect on the material nature of seeing. Her pink landscape paintings show the Dolomites in ways that ‘irritate the viewer’s gaze in order to elicit a longer and more conscious form of looking’ (BG9 Guide). The ‘overexposed’, washed out images and low-contrast style requires the viewer to find the right distance from the painting to achieve a visual fidelity. By extension, the viewer recognises their role in the image making, as faint blotches become mountains, empty spaces become clouds, and the darker areas coalesce into trees and forest once the negative space finds a context.

Reminiscent of Tacita Dean’s chalk works, the impermanence of chalk drawing has a sibling in Genadry’s play on the impermanence of vision. The image isn’t there until we find it, then recedes as we move away. Importantly, the image — once recognised — is then imprinted on the visual memory. As our brains cognitively overpaint choppy data sources, we continue to ‘see’ the image even when the original material is no longer decipherable.

One of Genadry’s long-term themes is how instability (war and crises) creates a ‘heightened perception’ (BG 9 Guide). Is it that violence and crises imprint a pattern that overlays the data we receive? That we continue to rephrase past experiences using indeterminate current data to paint a traumatic future? Maybe so. However, it’s worth noting that the same could be said for elevated positive experiences, and these pink mountains are a tangible way of restating that opaque yet ongoing optimism.

Lin May Saeed’s (1973-2023) works, focusing on the relationship between animals and humans, are a feature particularly important to the event. In a collaborative exhibition with GAMeC Bergamo, the work shown in Ortisei plays on how animistic myths are constructed by various cultures (particularly pre-Christian culture in the Levant/Middle East) and how the different facets of those stories present a vision of the animal world as related to the human one.

Her works use polystyrene carved into animal shapes, using the limitations of the material to suggest the sorts of sculpture and animistic iconography that ancient cultures once produced. While not impossible, it is difficult to carve curves in expanded polystyrene, and the rough planar sculptures of the animals seem ancient despite their late Modern material. The use of polystyrene, a controversial and polluting industrial material, also comments on humanity, ecology and nature. Saeed was deeply dedicated to animal rights during her lifetime, and this material continues to remind us of the anthropocene’s impact on the natural environment.

Works like Hathor (2017, relief) are strangely moving. The aesthetics of polystyrene, while repellent, are loaded with connotations of time, permanence, transience and ecology which hit the mark. Saeed’s use of paint has a fragmentary, totemic quality that conjures familiar references to archeological finds. In that way there is a sort of parallel to Damien Hirst Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable (2017) which riffs on the construction of yesterday’s cultural history by today’s cultural authorities — a form of myth-making and validation that is now a site of contest (post-colonialism) and protest (Stop-Oil).

Of course, using the symbolic motifs of the establishment, painted as comment or satire, is often the surest way to be included in those establishment collections. Saeed’s innovative use of polystyrene to reference antiquity is thus a statement on and a gambit for lasting impact. But polystyrene is a fragile product. If we look at the symbolic aspects of the work, her sculptures may disintegrate into white crumbs but those crumbs will remain forever.

A partner event is the Thinking like a Mountain (May 2024-25) programme, which champions local materials as an interplay between ecology, industry and artistry. At GAMeC (Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo) the processes which use local stone are used to create large modular desks and a heavy chess set. Based on Aldo Leopold’s Think Like a Mountain where he describes a holistic ecological perspective, the event mirrors the aims and themes of the Biennale, where issues around sustainability and community are approached through a shared artistic itinerary of collective performances and creative workshops. This programme will be documented as an online magazine as it unfolds.

The Biennale Gherdëina is a special event, benefitting from a spectacular natural location. The breadth of art on show is engaging and often profound. As well the artists mentioned above, special attention should be given the beetle sculpture in the town square by Julius von Bismarck, the haunting contemporary dance performance of Chiara Bersani, the material investigations of Laurent de Deunff and, of course, Sonia Boyce’s installation at Palazzo della Ragione, Bergamo. Beyond the art there are plenty of places to stay and eat, as well as acres of forest to walk through. It’s not a surprise that this part of the world contains art, scenic beauty and interesting crafts, but the alpine Biennale electrifies the connections between each of the elements that empower the charged viewer towards meditation and heightened reflection.

Biennale Gherdëina: The Parliament of Marmots

31 May – 1 September 2024

www.biennalegherdeina.org

Val Gardena, Dolomites. Italy.

Biennale Gherdëina 9, The Parliament of Marmots, curated by Lorenzo Giusti and associate curator Marta Paini includes exhibitions, performances and installations across Ortisei and Val Gardena from 31 May – 1 September 2024.

Thinking Like a Mountain at GaMeC, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, is a two year widespread cultural programme starting on 17 May 2024 and taking place across the Province of Bergamo.

Travel supported by GAMec and Biennale Gherdëina 9

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.