[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t’s easy to become jaded by causes.

It’s also easy to become self-congratulatory, smug with the lazy opinion that, since one’s own values are satisfactory, the responsibilitues of wider society are beyond personal control and to be viewed with a sigh of lament but little more.

Sloth, it is called, and it’s a deadly sin for good reason. Prejudice and hate have no firmer ally than the collective tendency to assume that someone else will sort it out. As Douglas Adams styled it: Somebody Else’s Problem. The privatisation of the Post Office, the dismantling of the health service, Syria, drones, the economic crisis. Somebody Else’s Problem.

Black History month started out in 1926, then termed ‘Negro History Week’. The terminology and timescale have since adapted to need. And it is needed. When education ministers attempt to whitewash Black History out of the National Curriculum, you know that *they*, at any rate, consider Britain’s Black History worthy of their less-than-benign attention.

Compiler of UK Black History Month’s timeline Gaverne Bennett answers some questions for Trebuchet:

If you had to pick one fact or event from the UK’s Black History, what would be most likely to surprise or astound the reader?

In the terms of the UK history what is probably most shocking is that black people were here at the time of the Domesday book of the 1200s, that the Normans had originally drawn up in an attempt to assess just what they had conquered!

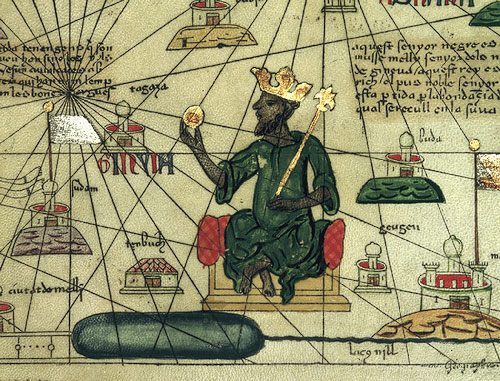

Internationally speaking,that the richest man in history was probably a black man, Mansa Musa I of the Malian empire, or that Haiti was once one of the richest places in the world is quite shocking, I think.

Tell us a little about the campaign to keep Mary Seacole on the UK national curriculum. Given that her time caring for soldiers in the Crimean War was previously accepted as worthy of study, did the threat to that status represent an effort to re-whiten UK education, in your opinion?

The attempt to remove Mary Seacole came as a shock to everyone. Noises had been made about changing the curriculum but nobody thought it would be so blatant. To remove near enough one of the few black characters that appear in the UK national curriculum gives you a sense that there was an attempt to rewrite black people out of British history again.

It is necessary to understand how long it took to get Seacole onto the curriculum to appreciate the strength of feeling when she was casually removed without discussion. I read about it on January 1st of this year and by January 5th thousands had signed the petition to keep her in it.

Everybody understood immediately the significance of removing Seacole. I think the whole episode shows that we have to be vigilant.

To what extent is it necessary to highlight the role of black people in history – surely history reflects the events of the past, regardless of the pigmentation of those acting in it?

Ideally that should be true but in reality that is not what has happened. In the last few hundred years arguably there has been a systematic attempt to belittle or ignore the role black people have played in history. For instance, I was shocked to discover that the Alexandre Dumas’ father played a critical part in French history, and indeed world history.

Tom Reiss recently resurrected his story in his Pulitzer prize winning book The Black Count. If history simply reflected the events, regardless of the pigmentation of those acting in it, Alexandre Dumas’ father’s name should be known to millions. The book shows how his pigmentation meant his story was buried.

General Alexandre Dumas by Olivier Pichat. Previous picture depicts Mary Seacole.

General Alexandre Dumas by Olivier Pichat. Previous picture depicts Mary Seacole.

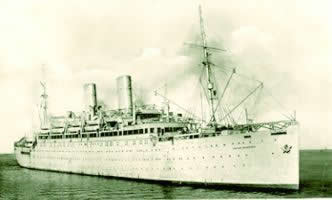

Your approach to the UK’s Black History takes us back to well beyond the Windrush. Is there a tendency for the Windrush era to dominate the impression of the black experience of Britain, and why might that be?

[quote]We can see the traces

of Windrush all around us

in living form[/quote]

I think this is for the obvious reason that the latest phase of black experience in the UK is rooted in, and can be traced back to, Windrush. We can see the traces of Windrush all around us in living form.

However, I think it did suit some people in the 1960s to give the impression that the arrival of black people was a totally new and alien experience. Once we see the black experience through a longer historical lens then it becomes easier to understand where Windrush fits in. Not just in terms of the black experience in Britain but British history itself. Going beyond Windrush forces the reader to go beyond the so called “island story”.

‘Lilting’ is a term popularised by DJ Wrongtom. Referring to 1980s advertisements of Coca Cola’s Caribbean-themed drink Lilt, it has since come to signify exasperation with the promotion of an artificial image of Afro-Caribbean culture that conforms to comfortable cliche: laid-back, dreadlocked stereotypes lounge about in the sun, living a carefree existence, oblivious to the White Man’s Burden. How much does Black History Month, in supposedly-enlightened 2013, still encounter that canard?

I must admit when I see an over preponderance of African drumming on a black history program I do worry.

What I find strange is how a symbol of resistance, of re asserting an African identity (an identity many people of African descent had hitherto rejected), dreadlocks, has been repackaged to conform to older stereo types of black people from slavery i.e. lounging “about in the sun, living a carefree existence, oblivious to the White Man’s Burden.” [quote]there is a tension

in Black history that

makes it all the more

interesting[/quote]

To a certain extent I think it can be said there is a tension in Black history that makes it all the more interesting.That is to say, it highlights the many struggles and centrality of people of African descent in making the modern world. However, there is another pull that tends to reduce black history to black music or even black people having to be entertaining in some way.

I think as long as there is need for a black history month this tension will continue. That is to say as long as there a world where Martin Luther King’s words still resonate; where we see protests like that around the Trayvon Martin case; or where the Lawrence family are still seeking justice, then it follows certain negative stereotypes with a longer pedigree may sometimes overshadow or entwine themselves in attempts to counter stereotypes.

Black history month itself challenges “Lilting” for it highlights the true history of places like the Caribbean, for example.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.