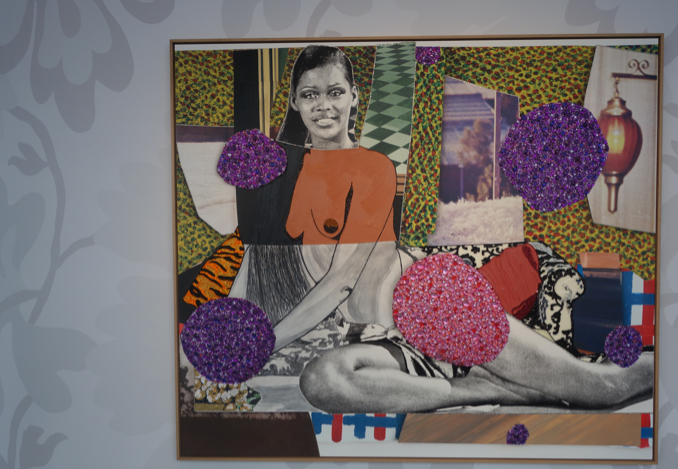

Mickalene Thomas, October 1975, 2019, mixed media

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]B[/dropcap]laxploitation is perhaps best exemplified by the 1971 film, Shaft, starring Richard Rowntree as the eponymous hero. With a hit soundtrack by Isaac Hayes released on Stax, the film was the first to feature a soul-funk soundtrack; designed, along with the film, to appeal to a black audience.

The Assertion and Insertion of Black Culture into Main Street

After the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the seventies brought limited wealth to a new generation of middle-class African-Americans. Positive and affirmative images of African-Americans had previously been few and far between. There were few role models for aspiring black adolescents because there were few aspiring black adolescents. Television medical dramas might typically portray white doctors alongside black hospital porters and support staff. Those few African-Americans newly entering the professions had to look largely to white success-stories to inform and represent their aspirations. The American dream was seen from the perspective of a culturally privileged white populace.

Shaft, therefore, marked a new direction. Ostensively, it represented the new freedoms afforded African-Americans in the new racially neutral and neo-liberal free marketplace. Is that true? Clayton Riley, an African-American commentator of the period, writes in the New York Times,

“Films like “Shaft” will be well received in this city because they provide Whites with a comfortable image of Blacks as noncompetitors, as people whose essential concern in life is making Mr. Charlie happy. It’s about that big, Black, historically delicious breast of Mammy being stuffed into the collective mouth of America’s White Kids of All Ages. It’s about Saturday night diversions being provided by the darkies, the plantation boss striding through the cabin rows to check out some of those plump and dusky belles.

Shaft, played by newcomer Richard Roundtree, entertains. He dresses expensively, lives downtown in a renovated plastic brownstone, and, of course, he sleeps around. All of this is a lie, in fact. Private investigators, real ones, work hard at dull jobs for small pay. Collecting dirt for shabby divorce cases and grabbing stray hands out of petty-cash boxes is what that life is about— “Shaft,” then, is twice removed from any acceptable truth.

We are also led to believe he is highly respected by the New York Police Department because he’s got so much machismo. “Where the hell are you going, Shaft?” barks a young cop who has not yet been exposed to our man’s rapier‐like wit. “I’m going to get laid,” is Shaft’s extravagantly hip reply, “where the hell are you going?” (Riley 1971)

Riley exposes the stereotyping he perceived in the blaxploitation movies. Shaft is a modern neo-liberal unfettered by such moral conventions as religion might demand. However, as Riley rightly points out, whilst on the side of the ‘good guys,’ he is nevertheless peripheral to the agencies of state. He enjoys the confidence of the local police chief, but stops short of being so regulated as to join the state established law enforcement agency. Blacks were to be seen as anti-establishment.

Blaxploitation, a portmanteau word eliding ‘black’ and ‘exploitation,’ is ambiguous between opening up a market for African-Americans on its positive side; and further abusing or exploiting them, on its counter-face. Riley’s splenetic expression gives vent to the latter in a manner thought politically necessary at that time.

Mickalene Thomas and Black Beauty

How might this cast light upon the work of contemporary artist, Mickalene Thomas? Thomas’ work includes images of African-American women of the seventies. This exhibition takes and uses images from Jet: Beauties of the Month pin-up calendars, published between 1971 and 1977. These were advertised as the first “black is beautiful” calendars. They were a spin-off from the weekly Jet magazine. Its Wikipedia page describes its weekly content thus:

“Jet (…) claims to give young female adults confidence and strength because the women featured therein are strong and successful without the help of a man. Since 1952, Jet has had a full-page feature called “Beauty of the Week”. This feature includes a photograph of an African-American woman in a swimsuit (either one-piece or two-piece, but never nude), along with her name, place of residence, profession, hobbies, and interests. Many of the women are not professional models and submit their photographs for the magazine’s consideration. The purpose of the feature is to promote the beauty of African-American women.” (Wikipedia 2019)

This presents a challenge to the orthodox view of beauty and the glamour that attaches to it; a challenge that, on the face of it, places African-American women as differently beautiful to their white counterparts. Under such a conception the beauty of a woman (conceived in terms of appearance) is relativized to race – so that race becomes a category within which different norms of beauty operate.

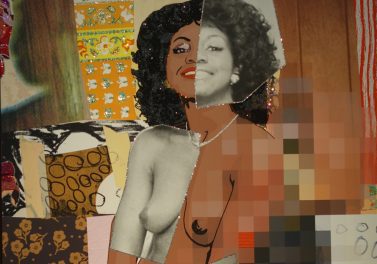

Mickalene Thomas, July 1977, (detail), 2019, mixed media

Thomas’ work attends to the notion of beauty as attraction. The Jet calendar girls are soft pornography; the models clothed in bikinis or topless; or fully nude but discreetly posed; (unlike the magazine’s “Beauty of the Week”). There is, therefore, a political point in presenting the challenge to the stereotypes of beauty that foreground the “blonde bombshell” as the ultimate object of desire. And this is where Thomas lifts the work to a different level of beauty. Her work is beautiful, as painting; the more so because it uses these ‘glamour’ images of nude African-American women in ways which exploit the western modernist canon. The fact that these photographic images are often grainy and/or black-and-white gives them a peculiarly dated feel. Combined with her other compositional elements, these complex images themselves turn what Riley might have thought negative blaxploitation into positive images.

The Intersection of 70s Imagery with Contemporary Art-Making

The other contemporary elements include pixelation, the use of solid matte colours, seventies’ wallpaper print backgrounds, metallic and rhinestone surfaces. The beauty of paintings is to be set apart from the beauty of the natural world. It demands normative standards. Thomas achieves this.

‘Beauty,’ we are often told, ‘lies in the eye of the beholder.’ That is a pre-philosophical position that is rightly challenged by those whose concerns are with value. It throws down the gauntlet, so to speak. Immanuel Kant pioneered an aesthetics that faces down that challenge.

Kant on Beauty

Kant conceived of beauty under two structurally independent conceptions. The first of these is free beauty, the second adherent. Each conception depends upon a feature of our mental apparatus engaged in our understanding of the world – our engagement with it. (And, if so, neither conception is merely subjective.) We sort the world out in general terms. We bring concepts to bear upon the sensory input we receive through, and in, perception. I learn to recognise dogs, daffodils, dermatological disorders, doormats, didgeridoos and dandelions; amongst other things. According to Kant’s view, I can do this because my imagination automatically sorts perceptual input into conceptual order. In his epistemology, Kant talks of this as the ’manifold of perception’. The manifold is the action of mind in its regulation of sensory input.

Kant’s free beauty is accessed when we look at the patterns of nature; at such times we stop short of sorting the sensual input under conceptual determination. I look only for structure across the sensations themselves. I therefore withhold the classificatory operation of my imagination in order to have an experience independent of conceptual content. Beautifully patterned nature is simply beautiful on account of its form alone. We are constrained by our rationality to recognise formal beauty; our rationality, that is to say, demands the recognition of such beauty.

Beauty without conceptual content, however, looks as if it cannot go further than geometric design in either two or three dimensions. But since everything can be described by either a two or three dimensional geometry, there seems to be no ready way of saying which contentless geometrical arrangements should be regarded as beautiful.

Sartre’s Existential Seeing

In Jean-Paul Sartre’s novel, Nausea, Roquentin considers circles and music in geometrical terms; and compares these with his confrontation with teeming existence. In the novel Roquentin is sitting in a park and staring at the root of a chestnut tree:

“In another world, circles, musical themes keep their pure and rigid lines (…) A circle is not absurd, it is clearly explained by the rotation of the segment of a straight line around one of its extremities. But neither does a circle exist. This root, in contrast, existed in such a way that I could not explain it. Knotty, inert, nameless, it fascinated me, filled my eyes, brought me back unceasingly to its own existence. In vain I repeated, “This is a root” — it didn’t take hold any more. I saw clearly that you could not pass from its function as a root, as a suction pump, to that, to that hard and thick skin of a sea lion, to this oily, callous; stubborn look. The function explained nothing: it allowed you to understand in general what a root was, but not at all that one there. That root with its color, shape, its congealed movement, was beneath all explanation.” (Sartre 1949, 127)

It is an open question as to whether such experience is coherent, let alone possible. Roquentin tries to unhinge conceptual content from experience; and, in so doing, becomes unhinged himself:

“All at once the veil is torn away, I have understood, I have seen… The roots of the chestnut tree sank into the ground just beneath my bench. I couldn’t remember it was a root anymore. Words had vanished and with them the meaning of things, the ways things are to be used, the feeble points of reference which men have traced on their surface. I was sitting, stooping over, head bowed, alone in front of this black, knotty lump, entirely raw, frightening me. Then I had this vision. It took my breath away. Never, up until these last few days, had I suspected the meaning of “existence.” I was like the others, like the ones walking along the seashore, wearing their spring clothes. I said, like them, “The sea is green; that white speck up there is a seagull,” but I didn’t feel that it existed or that the seagull was an “existing seagull”; usually existence conceals itself. It is there, around us, in us, it is us, you can’t say two words without mentioning it, but you can never touch it. When I believed I was thinking about it, I was thinking nothing, my head was empty, or there was just one word in my head, the word “being.” Or else I was thinking — how can I put it? I was thinking of properties. I was telling myself that the sea belonged to the class of green objects, or that green was one of the qualities of the sea.” (idem.)

Sartre is not concerned with aesthetics in this passage. He is trying to get behind perception and access the things in themselves. This picks up on a theme in Kant’s metaphysics which posits noumena as such. We cannot know such things as we are confined within the realm of experience and have access only to phenomena; and phenomena are contentful; they are conceptually structured. Sartre is also considering an epistemological question. How do I (and why should I) collect things under descriptions?

Notwithstanding Sartre’s epistemological and metaphysical focus, we can, following Kant, ask how the ‘manifold of perception’ constrains our conception of beauty? The troubling thing for aesthetics is that free beauty, being, ex hypothesi contentless, nevertheless requires phenomenal properties.

Adherent Beauty

Adherent beauty, by contrast, brings the object of interest under its governing concept; and so, inherently, it has content. I see a horse with a smoky blue-black shining coat, its long tapering head and its elegant stride; and I judge it beautiful, as a horse. The concept of what it is – a horse – now plays a role in my judgement. That is why, earlier in this essay, I was able to write that Thomas’ work is beautiful, as painting. Kant’s view not only permits this, it demands it.

Kant’s view of Fine Art is that it is an adherent beauty – pace Greenberg and many artists and art historians who take beauty in art to be free and, therefore, formalist. Kant had a view that each of the arts was medium specific; and that it was this medium specificity that determined the kind of beauty that each art could attain. For Kant, painting is a representational art. It is in the nature of painting that it strives toward depicting objects, scenes or events, in such a way that those objects scenes or events reveal aesthetic ideas that would be otherwise beyond our conceptual grasp.

If the beauty of Fine Art is, as Kant contends, adherent beauty, we need not, normally, concern ourselves with free beauty. However, the case of Mickalene Thomas uses the norms of natural beauty (at one particular historical moment) in order to reveal an aesthetic idea about otherwise hidden political structures within our visual culture. What is so striking about the work is that it makes her paintings beautiful – in that they reveal a kind of truth; they make things transparent which had hitherto seemed opaque; or that we had grasped dimly.

The Beauty of Women

Are women beautiful: and, if so, what account might be given of their beauty?

Humans can be (and perhaps ought to be) sexually attractive to other human beings. Attraction stirs in us a basic biological function. Beauty, however, outstretches the compass of sexual attraction. A human being can be beautiful, and judged so, by another, even if that other is not attracted to them. Attraction is a form of engagement, or at least an incitement to engage, with the world. Beauty is not. Attraction, that is, involves desire, whilst beauty does not. An early argument for the distinction appears in Plato’s Phaedrus (Plato 2005), where Socrates discusses with Phaedrus the nature of beauty and the power it exerts. Socrates is trying to provide a place for beauty that is above and beyond engagement. It is an early argument to the effect that the enjoyment of beauty is not a form of consumption.

Platonic Conception of Erotic Beauty

Socrates conception of beauty, in Phædrus, regards earthly beauty as memory of divine beauty, glimpsed by the pious as they look out from the heavens. In heaven, however, real beauty is not visible but is purely intellectual. (“Glimpse” and “look out”, therefore, need to be read as figurative speech.) So, earthly beauty, the beauty of a young boy, for instance, is to be seen as an earthly manifestation of an idea – a revelation.

Socrates is discussing love as an aspect of beauty (Eros). As such he is concerned with desire and our appropriate response to it. In his palinode he argues that such desires as follow from the love of a young boy should not be followed in pursuit of bodily pleasure. The lover should rather use the experience of beauty to reflect upon the heavenly nature of love. Thus, real beauty exists for intellection alone and is manifest in heaven; but, as Socrates demonstrates, it is available to us here on earth through our perception penetrated by intellect. So, beauty, even when considered as Eros, ought to lead us from earthly perception toward heavenly intellection. We, earthbound creatures, do not see such heavenly beauty, but we gain indirect access to it via the world as seen.

Kant, Plato and Rational Beauty

In Phædrus, Socrates, too, holds that there is a place for reason in judgment.

“[I]n every one of us there are two ruling and directing principles, whose guidance we follow wherever they may lead, the one being an innate desire of pleasure; the other, an acquired judgment that aspires after excellence. Now these two principles at one time maintain harmony, while at another they are at feud within us, and now one and now the other obtains the mastery. When judgment leads us by sound reason to virtue, and asserts its authority, we assign to that authority the name of temperance; but when desire drags us irrationally to pleasures, and has established its sway within us, that sway is denominated excess.” (Plato 2005, 237-8)

According to Kant, the genius makes art that embodies aesthetic ideas; and these are,

“inner intuitions to which no concept can be completely adequate. A poet ventures to give sensible expression to rational ideas of invisible beings, the realm of the blessed, the realm of hell, eternity, creation, and so on. Or, again, he takes [things] that are indeed exemplified in experience, such as death, envy, and all the other vices, as well as love, fame, and so on; but then, by means of an imagination that emulates the example of reason in reaching [for] a maximum, he ventures to give these sensible expression in a way that goes beyond the limits of experience, namely, with a completeness for which no example can be found in nature.” (Kant 1987, 182)

Beauty Apprehended; and not Consumed

Socrates argues for the apprehension rather than the consumption of beauty, as does Kant. Art is not supposed to satisfy our needs. We apprehend the visual arts via visual perception, but we do not merely delight in it. It must bring to mind some greater truth (Socrates) or mobilise our minds by quickening them to grasp aesthetic ideas (Kant).

Accordingly, whilst Thomas uses soft-core pornographic images of African-American women, these dated images are recruited to a contemporary commentary revealing the political structures out of which our visual culture has developed. These are not works of art for African-Americans. Rather they are works of art for us. And we are those to whom the works reveal an aesthetic idea of the preposterous nature that beauty could ever have been racialised. We are like the souls in Socrates’ heaven who have glimpsed (figuratively) an eternal truth about the beauty of humanity, in general. We comprise black, white, gay and gender-fluid art lovers, who recognise in Thomas’ work a beauty independent of our specific desires.

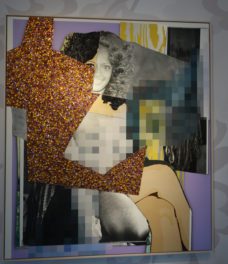

Mickalene Thomas, January 1976, 2019, mixed media

Thomas and the Recruitment of Culture to the End of Fine Art

The beauty of the work is not just that it sees the beauty of humanity in these African-American models; it is also that in seeing erotic beauty at a distance – through the medium of painting – it not only de-racializes the identity of the sitters, it de-sexualizes the erotic charge inherent in the original photographs. Of course, we recognize the racial identity of the women in the photographs; but we are brought to see these women in the context of an art practice that, as noted above, ‘lifts the work to a different level of beauty’; one that is imbued with an aesthetic idea.

That idea is furthered by the distancing strategy of paint, rhinestones and metallic surfaces that sharpen the composition by relating its content to the history of western art that had hitherto afforded no place for the imagery of black models.

In rejecting that censure, Mickalene Thomas serves visual culture in general, but also painting in particular.

References:

Kant, I., (1987) Critique of Judgment, (trans.), Werner S. Pluhar, Indiana: Hackett Publishing

Plato (2005) Phædrus London, Penguin

Riley, C., (1971) “A Black Movie for White Audiences?”, New York Times, 25th July

Sartre, J-P., (1965) Nausea, New York: New Directions, 1949

Wikipedia (2019) “Jet (magazine),” site edited and updated on 21 September 2019, at 17:36 (UTC). Accessed on 7th November 2019 at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jet_(magazine)

Mickalene Thomas: beautés du mois was at: Galerie Nathalie Obadia, r. du Cloître Saint-Merri, Paris

Wed 25 Sep 2019 to Sat 16 Nov 2019,

Mon-Sat 11am-7pm

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.