[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]F[/dropcap]or the past decade, there’s been a hypnotic, bluesy-rock sound coming out of the Sahara.

If you’re keyed into the African music scene, you have surely heard of Tinariwen, the band of former refugees and freedom fighters who have been making a name for themselves alongside the likes of TV on the Radio, Carlos Santana, and Robert Plant. While they’ve attracted some big names over the years, they have some competition rising rapidly through the ranks in the form of a young Nigerien named Bombino, who is breaking out on his own in a big way.

To understand the musicians, you have to understand their land. Tinariwen means “Desert” in the band’s native Tamashek language. Tamashek is the soft, guttural tongue spoken by the Tuareg, the people who have plied the Saharan sands for centuries. They are the desert pirates, the raiders who once controlled the trade routes that brought salt, gold, and ivory into the Mediterranean.

Like the Arab Berbers, to whom they are related, the Tuareg, at the time of European conquest had no state of their own, no major political powers. Instead, they occupied a loose-knit clan system, spread over what would become Algeria, Libya, Mali, and Niger.

Because of their low population density and their choice to live in one of the most inhospitable regions in the world, the Tuareg have never truly been conquered or drawn into any state system. At independence, when France turned its colonies over to the indigenous Africans, the Tuareg were left out of the political power plays. They have since staged numerous rebellions over the past half century for a claim of the economic pie or, at times, their complete independence.[quote]During the last campaign

against the Tuareg in

2007, Niger banned

guitars from the restive

North. Never let anyone

tell you that music

doesn’t have power[/quote]

That’s where Tinariwen comes in. The band’s founder, Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, first picked up a guitar in the refugee camps of Algeria. He met many of the band’s future members in Muammar Qaddafi’s military training camps, a pet project that he hoped could form an elite African fighting force.

A few of the guys from Tinariwen would go on to fight in further rebellions before settling down to the quiet life of the musician, finally hitting it big in the late 90s with an explosion of interest in African music along with the likes of Ali Farka Touré, Amadou and Mariam, and Oumou Sangaré. Since then, they have been one of the best known acts on the world music circuit, touring Europe, North America, Japan, and Australia.

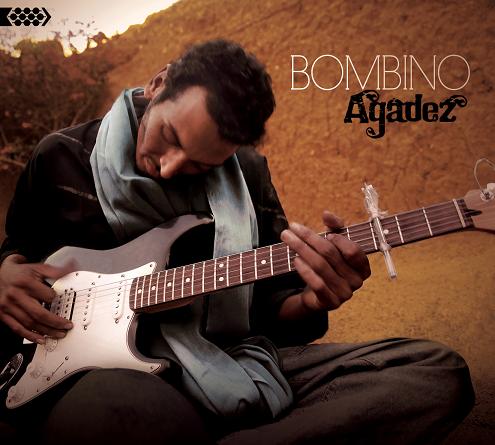

There’s a new name on the scene, however. Omara “Bombino” Moctar is a 33-year old guitarist from the northern Agadez Region of Niger, a landlocked country consumed by the Sahara. Like Ag Alhabib, Bombino picked up his guitar skills in Algeria’s refugee camps. When he exploded onto the world music stage with his first album, Agadez, in 2011, Bombino quickly set himself apart from his predecessors by working the traditional hypnotic chords with some electric pick work.

There are shades of Jimi Hendrix and Mark Knopfler on his first album, major influences from his days as a teenager in Algeria and Libya.

Agadez attracted the attention of Black Keys’ frontman Dan Auerbach, who produced Bombino’s follow-up album Nomad, which came out earlier this year. The album was cut in Nashville, appropriately enough, and has some of Auerbach’s mellow, open-strung fuzz. Throughout it all, however, Bombino never loses that unique sound – the liquid flick of the desert sands.

I had a chance recently to catch Bombino in Detroit at The Magic Hat, a smaller venue out north of 8 Mile. It’s a bar that attracts alternative types, the Detroit hipsters who’ve brought the metropolis back from cultural oblivion while simultaneously making some parts of the Motor City insufferable.

Bombino began his set seated, with an acoustic guitar. This is the music of the desert, the kind played around a fire while the stars shine brighter than anywhere else in the world. It’s a slow, cool feel backed by the drumming of a calabash, the large, hollowed-out gourd used to carry grain during the day and to set a rhythm at night.

Music has been, at times, a weapon for the Tuareg, a rallying cry. During the last campaign against the Tuareg in 2007, Niger banned guitars from the restive North. Never let anyone tell you that music doesn’t have power. These aren’t war songs, however. Bombino insists that his guitar isn’t a gun. Instead, it is a hammer that he will use to build his people’s homes. Instead of leading men into the brink, they are melodies about the thrill of young love, friendship, patience, and a longing for home.

For the second half of the show, Bombino and his band are on their feet, their calabash player moving to a traditional set as they crank up the heat on an electric show. Bombino dropped the acoustic for a Fender Stratocaster, the stone cold classic of the desert sound. I’ve never seen an African band play without at least one Strat in the house.

It was in the show’s second half that Bombino really starts to burn and sets himself apart as the hottest young artist coming out of the Sahara. The licks are clean and infectious, and it wasn’t long before he had the Detroit hipsters on their feet and dancing.

Perhaps what I liked best about Bombino, however, was his interaction with fans after the show. Instead of jetting off and leaving everyone behind, Bombino was there after the concert at the merch table, signing records, DVDs, and discs. He’s a humble guy, one who gives himself to those who’ve come to see him. Though he doesn’t speak much English, one of our group knew some Hausa, one of the primary languages spoken in Niger, and he was soft-spoken and modest in our brief interaction.

Though his profile is growing, Bombino is still a relative unknown. But he won’t be for long. This year, he toured the US at Bonnaroo and the Newport Folk Festival. He’s opened for Amadou and Mariam, and, in a show I cried at missing this past summer, for gypsy punks Gogol Bordello in Milwaukee.

If you haven’t heard of him, go out and buy his album. Don’t listen on Spotify. If you must, get a sampling from Youtube, or just trust me. Buy either of his albums. Buy both of his albums. Try to track down the desert sessions from his days in the desert.

Get it all. You won’t regret it.

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.