[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]L[/dropcap]et’s visit Scarfolk.

I grew up in the small Devon village of Stoke Gabriel, which sits at the end of a small creek on the River Dart estuary. Its economy was once based on farming and salmon fishing, though now it’s both a holiday destination for day-trippers and a popular place to retire. But back in the 1980s when I was in my teens and the place was still a tad more rural than it is today, I became convinced that the village had a darker secret. I was quite certain that it had its very own coven of witches.

The evidence was clear.

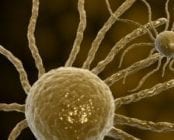

First, the village has a famous ancient yew tree in its churchyard, a thousand years old.  It’s said that if you walk backwards around it seven times your wish will be granted.

It’s said that if you walk backwards around it seven times your wish will be granted.

Then there’s the church, which has a couple of beautiful Green Man carvings.

During renovations of one of the village pubs, the Church House Inn, built in 1152, builders discovered the remains of a three hundred year-old mummified cat, stuffed up behind the chimney breast, and quite obviously put there for occult or apotropaic purposes.

Once, driving home at night, we saw a bonfire on top of one of the surrounding hills with what looked like people dancing around it. “That’ll be the local coven” my father joked.

And then there was the time I found what I thought was an altar, improvised from feathers, driftwood and other flotsam, down on the foreshore. It all pointed to one conclusion: witches among us.

Cognitive Science has a name for this sort of thing: confirmation bias, the process whereby one selectively fits evidence into a pre-existing set of beliefs such that the two become mutually reinforcing.

I prefer the older, Freudian term wish-fulfillment, which makes me sound less like a faulty appliance and allows me a genuine psychological need behind the fantasy.

[quote]The idea of occult

goings-on taking

place behind the

civilised veneer of

English village life

has been a trope

of popular fiction

since the nineteenth

century[/quote]

In my case the witches were not satanists, but ancient, benign, magic-wielding earth-worshippers, who had somehow persisted secretly in the village since ancient times. Sooner or later they would recognise me as one of their own, initiate me into the mysteries and rescue me from a life of dull mundanity. Classic fairy tale stuff.

But there’s another, less psychological reason why I ended up convinced of the witches’ existence. The idea of occult goings-on taking place behind the civilised veneer of English village life has been a trope of popular fiction since the nineteenth century. It was particularly zeitgeisty in the 1970s and 80s and I was steeped in it. I heard it on radio plays. I read it in Alan Garner and Susan Cooper. I watched it in Doctor Who, The Changes, The Children of the Stones and later, Robin of Sherwood. It appeared in horror movies, The Devil Rides Out and more famously The Wicker Man, later parodied in Hot Fuzz. Not surprising, then, that I thought it might really be happening at home.

If you think I’m just making excuses then check out the wonderful Scarfolk blog:

‘Scarfolk is a town in North West England that did not progress beyond 1979. Instead, the entire decade of the 1970s loops ad infinitum. Here in Scarfolk, pagan rituals blend seamlessly with science; hauntology is a compulsory subject at school, and everyone must be in bed by 8pm because they are perpetually running a slight fever.’

Like Hot Fuzz it’s a delightful parody but proof that I wasn’t alone. Children who grew up in the 70s clearly lived in a completely different hauntological dimension, but one, as Stewart Lee confirms, that we could do well to bring back.

Interestingly, about fifteen years ago, and long after I’d left, some druid friends moved to Stoke Gabriel. They held ceremonies in the woods not far from the beach where I found that ‘altar’. I could’ve gone along at any time if I’d wanted. I never did.

Reality could never live up to expectation.

A writer and a folk musician, Andy is the author of ‘Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom’ and has published a range of articles and academic papers on subjects as diverse as psychedelics, paganism, bardism, environmental protest, fairies, shamanism and evolution. A modern day troubadour, he plays mandolin, writes songs, and fronts darkly crafted folk band, Telling the Bees. A leading exponent of the English Bagpipes, he plays for brythonic dancing in a trio called Wod.