Psychedelic visions combined with a skill for geometry and a lexicon that owes more to mathematics than romanticism, Bramha’s exhibition brings rave culture into the light. But can his work maintain its relevance outside of its countercultural antecedents?

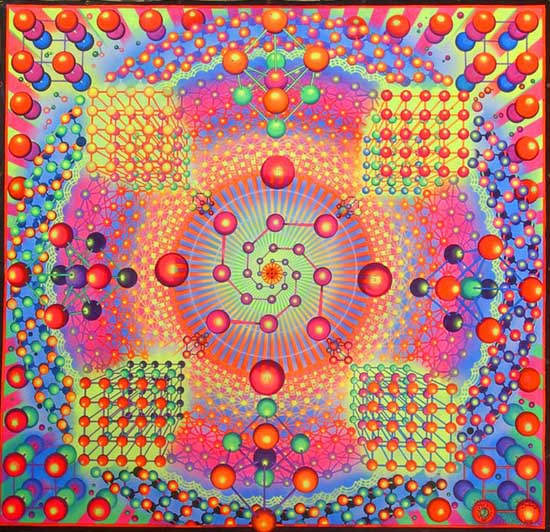

Lurid designs emanating from Brahma’s canvases wear their ethnic references unashamedly; Hindu, Buddhist, South American, and Kabbalah; all rendered in fluorescent colours, seem to conjure aspects of spiritual rituals and their appropriation by travelling hippies on trips of shared individuality.

Since the Sixties Brahma has been associated with Raja Ram, from his early incarnation as a member of West London folk-psyche group Quintessence to his role in the development of what became psychedelic trance. As such, Brahma’s work will be familiar to anyone that has been to a 90s rave or walked through the markets of Camden and any expectation of seeing new ideas are mollified by this.

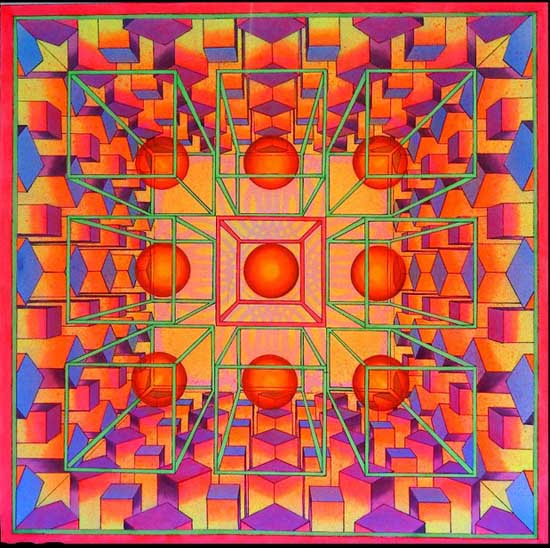

Whether or not Brahma originated the style that has been replicated on innumerable t-shirts, squat party backdrops and Israeli album covers is up for question. Given his location at the epicentre of the psytrance movement it seems likely that anyone visiting the exhibition is seeing either one of the main architects or at least a prominent avatar of a particular artistic movement. Looking at the work from this pop-cultural perspective we can think about how Brahma’s work functions as a part of cultural history.

While it seems too soon to consider the backdrops from primordial raves to be pieces of collectible art, as a generation collectively remembers that 20 odd years have passed nostalgic memory inevitably transforms into cash value. Understanding that the works on show are in essence scaled down reproductions of those much large event canvases the viewer is drawn to consider their functional purposes in situ. They are supposed to lift the viewer into making higher narratives of bright positivity during moments of peak experience however in the restrained environment of a private view they still manage to hold one’s attention.

Looking at Brahma’s work it’s hard not to be tainted by the poor derivatives previously seen in nightclubs but on close inspection the quality of his pieces stand out. Within his highly geometric works the lines and perspectives are faultlessly captured and the stark almost machinelike precision allows the use of colour to create a moving sense of depth and meaning.

The recurrence of shapes and geometry indicates Gematric meaning (number symbolism used in Greek and Abrahamic mystical language systems) that seems fleetingly close to comprehension but remains elusive, almost choosing to be purposely arcane. Staring at the fluorescence for a even short while starts to strain the eye, if there is a higher truth to be found within the canvases the danger is to be literally blinded by the light. This, in itself, might be a parable on the scene that accompanied Brahma’s work.

Conversely, the psychedelic cultural reproductions of ‘ethnic’ religious works seem less convincing, perhaps even gratuitous. Can we separate these images from the situations that spawned them; Westerners arriving in the Third World locales forcing a cultural hybridism on the existing peoples, before commercialising these myths and images piecemeal for the Gap year market? It’s hard to say, as the benefit versus the social impact of hippy trail economics has been overtaken by larger forces of globalisation both financially and culturally.

Trance, as with any musical genre, remains vital as long as it mutates, draws in new material, and stays more or less popular depending on the vicissitudes of cheap travel, youth tastes, and the financial incentives of the industry that promotes it. The same cannot be said for the psychedelic element embodied by Brahma’s work. Divorced from its attendant function as visual ‘food for thought’ to accompany the group experience of a rave, these works are shining monuments to past moments. Heady stuff, sure, but colder on gallery walls than in the flush of youth.

Presented by Elizabeth Smith: Brahma Exhibition runs from 16th March to the 4th April at the Muse Gallery

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle