[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he Collecting Gauguin Exhibition, which was staged for The Courtauld’s 2013 Summer Showcase, epitomised the gleeful expectations of a visit to an institution renowned for its enviable collection of post-impressionist paintings.

The paintings hum with a crowd-pleasing timelessness, instilled within their vibrant daubs of paint and bold gestural lines.

Time-worn is rather the epithet that one might attribute to prints. The etched lines can seem like an antiquated trace – a preparatory step before the grand showcase of the finished painting. Some archaeologists dedicate their lives to the exploration of these ley lines, this overlooked and half forgotten topography; lying quiet beneath the acid free sheets scarcely rustling in archival drawers. The less willing to disturb the dead, however, will stay clamouring at the altar of showstoppers such as ‘Nevermore’ and ‘Bar at the Folies- Bergere’, rich with reassuringly chartered territory in the permanent display.[quote]This is not only a collection of

greatest hits… but also an

investigation into the possibilities

opened by different printing

techniques[/quote]

What if, however, these unassuming offerings were in fact instilled with the potential to inspire, to ignite and to discover? What if rather than mere recordings or ghosts of greater figures they were sites of poetic creation, of freedom and realisation? It is this question that the selection of 30 works – from some 24,000 in the gallery’s holdings – in the Breugel to Freud exhibit pose, continuing a series of sympathetically curated shows by The Courtauld which have highlighted key threads of art historical narrative from their vaults.

If one pauses to listen, then there are some quietly iconoclastic voices to be heard.

The display showcases a selection from the gallery’s vast collection, which in spanning 500 years, is the result of an array of individual gifts –Sir Robert Witt being the largest contributor, a co-founder of the gallery and notable for establishing an image bank library for art historians. This is not only a collection of greatest hits, however, but also an investigation into the possibilities opened by different printing techniques. Evident in the work on display is both the social implications of printing – as a means to increase the accessibility and dissemination of art – and the imaginative potential of artists who, freed from the constraints of painting, are able to sing with a refreshingly improvisational style.

Nicolas Béatrizet’s ‘Last Judgment after Michelangelo’ is an epically realised construction of ten plates that piece together in a jigsaw-like arrangement, making the figures flow throughout the composition – rather than being constricted by the confines of a conventional frame. Begun in 1562, one cannot help drawing a thoroughly modern comparison to the Matisse cut outs currently on show at Tate Britain. Matisse’s aim to make work that lived and breathed within and alongside life, resonates with the narrative of Béatrizet’s masterpiece – in that the longevity of the plates allowed for the spreading of Michelangelo’s work throughout Europe, outside of what became the continent’s printing powerhouse in Rome.

Out of three great master printers, one of Piranesi’s ‘Carceri d’invenzione’ (or Imaginary Prisons) is perhaps the most emotive and visually arresting. Applying his experience in architecture and set design, Piranesi deftly erected labyrinthine Surrealist structures that evoke a Kafka-esque perspective on real life spaces. The psychological depth of the blurred, frantic figures and monumental ruins is conveyed through a rapid etching technique that distorts and darkens the subterranean views. The intensity of the Moore-like gestures is heightened within the show by the juxtaposition with Canaletto’s ‘Portico with A Lantern’– a magical-realist depiction of Venice.

By harnessing a similar range of mark making, an imaginative projection of the beauty of a sunlit architecture is achieved – wherein the hundreds of close lines that denote the sky convey a majestic variety of subtle tones of light and dark. The humidity of the rising city heat is almost palpable.

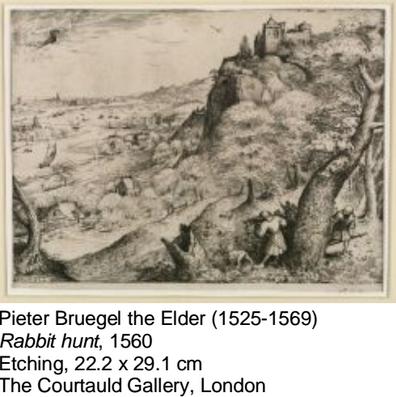

It is this liberation, and the ability of etching to render scenes with a naturalism comparable to the fluidity of drawing, that is showcased in the inevitable rich pickings from the late 19th century. It is here that the possibilities of printmaking are truly expanded, picking up where the more secular terrain being explored as early as the 16th century by those such as Pieter Bruegel The Elder– whose ‘Rabbit Hunt’ (1560) on show here is a hauntingly enigmatic landscape which is interestingly the only example executed by the artist himself – left off.

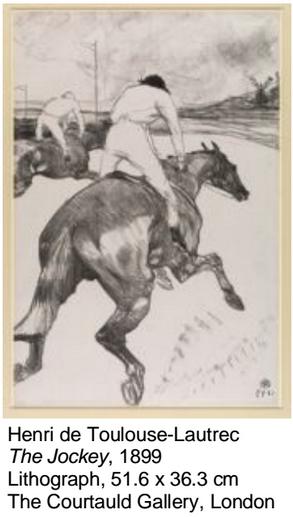

The French avant-garde led the way with Edouard Manet paying homage to Old Masters and Paul Gauguin reviving the woodcut. The highlight from this era, however, is Toulouse Lautrec’s lithograph ‘The Jockey’ (1899). Although better known for his social observations of the Parisian underworld, Lautrec was commissioned in the late 1800s to produce a series of equestrian prints that reflected his lifelong interest in horseracing. There is poignancy about the print since – originally commissioned as a series – it also marked the beginning of Lautrec’s ultimately fatal descent into alcoholism and so is the only one of its kind that was ever completed.

This does not detract from the magnificence of the vigorous lines which, convey the dynamism and energy of the union between man and beast as they tear into an abyss of white paper.

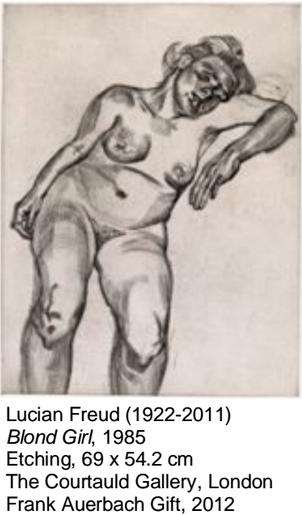

Offerings from Picasso and Matisse further exemplify how a dedication to experimentation injected renewed vitality into 20th Century printmaking; pre-empting the improvisational approach redolent in Lucian Freud’s ‘Blonde Girl’, a gift by the artist Frank Auerbach. Dispensing with the need for preparatory drawings, Freud worked directly onto the etching plate, erasing and adjusting as he went – meaning that the finished print bears the ghostly traces of its materialisation.

Offerings from Picasso and Matisse further exemplify how a dedication to experimentation injected renewed vitality into 20th Century printmaking; pre-empting the improvisational approach redolent in Lucian Freud’s ‘Blonde Girl’, a gift by the artist Frank Auerbach. Dispensing with the need for preparatory drawings, Freud worked directly onto the etching plate, erasing and adjusting as he went – meaning that the finished print bears the ghostly traces of its materialisation.

Coupled with the fearless draughtsmanship, our attention is drawn to the raw fleshiness of the free-floating form – humanity exposed in all its majestic fragility.

Indeed, the function of printing as a trace of the human condition has earned it a comfortable place within the folds of contemporary conceptual practice. A pleasingly contemplative offering from Chris Ofili– a small scale monochrome mass of compressed swirling lines, stands in stark contrast to his colourful, socially astute paintings, yet retains all the dynamism of his famously multi-layered compositions. As a psychologically charged, diary-like observation of place, its nomadic context is dovetailed by the adjacent fragile grid of Linda Karshan. Her technique of imbuing a minimalist conceit with a highly personal, gestural performance by choreographing patterns as she manoeuvres around the sheet of paper, have the same humanist pathos of the fleeting agility in Eva Hesse’s work.

It is fitting perhaps that the show is complemented by a response from the students of the MA Curating the Art Museum Programme:

Impress: Print Making Expanded in Contemporary Art . In highlighting how traditional printmaking has been re-imagined in contemporary art, the exhibition questions the very notion of what constitutes a print and, foregrounds the notion of printmaking as an independent and groundbreaking art form.

No doubt many will make a beeline back to the safer ground of Van Gogh’s ear but, there is still drama aplenty to behold away from the turpentine odours.

Breugel To Freud: Prints from The Courtauld Gallery

19 June – 21 September 2014

For further information see the gallery website

[button link=”http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/exhibitions/2014/prints/index.shtml” newwindow=”yes”] Event Website[/button]

‘Blond Girl’ © Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Art Library